Introduction

The banking sector has globally witnessed multi-dimensional transformations in recent years. Banks are constantly modernizing their business strategies to keep up with the evolving regulatory requirements, the varying demands of different customer segments and the radical shift in technology (Institute of Bankers Malaysia, 2014; Ernst and Young, 2018). Therefore, banks need leaders who understand such transformations and can manage change effectively. As emphasized in (Institute of Bankers Malaysia, 2014), external changing factors can be managed with the support of the right set of talents. Globally, due to a severe shortage in banking talents, banks are struggling with the challenge of attracting and retaining the right people (Ogbeta, 2015; Ernst and Young, 2018).

Although the number of specific emerging countries is increasing (Chepkwony, 2012; Mawlawi and Fawal, 2018), there is still limited research on talent management (TM) in the banking industry (Chepkwony, 2012). Most of those studies examine the role of TM strategy in the banking sector generally or in the private/public banks in particular. They focus on investigating banks’ TM practices, challenges and impact on organizational outcomes such as employees’ performances, engagements and retentions. Limited research, if any, explores talents and TM conceptualization in the banking industry.

In relation to the Vietnamese context, human resource (HR) planning programs in the banking sector have been sanctioned by the State Bank of Vietnam for the period 2011-20 (State Bank of Vietnam, 2012). A number of public and private banks invested concerted effort in developing a capable HR (talent) (Tran and Vu, 2015; N. Anh, 2018). Despite such effort, TM is still an emerging issue in the country. According to the State Bank of Vietnam (2012), most of commercial banks have improved their HR management schemes to attract and retain talents; however, their HRM practices still involve significant limitations. Generally, some recently-developed HRM studies found that HR development is associated with key stages of the country’s economic development (Zhu and Verstraeten, 2013; Nguyen et al., 2018). Conversely, limited research focused on TM in the country’s context. Those studies mainly investigated the ways of attracting and/or retaining Vietnamese talents (Froese et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2012) without a clear focus on the conceptualization of talent and TM. Based on this gap, there is a need for an empirical study which (i) postulates the conceptualization of talent and TM in the Vietnamese banking sector and (ii) identifies similarities and differences between public (state-owned) and private employers in that sector regarding how they conceptualize talent and TM.

Drawing on qualitative data from semi-structured interviews conducted with various echelons of bank managers, this study aims to address the following research questions:

- How do employers in the banking sector in Vietnam conceptualize talent and TM?

- In what ways are the conceptualization of talent and TM practices similar or different between public banks and private banks in Vietnam?

Furthermore, this study addresses TM in its various forms; both theoretically and methodologically and cuts across various related fields (Al Ariss et al., 2013).

Literature Review

Talent Conceptualization

One possible explanation for the conceptual ambiguity of the word ‘talent’ is its history – considering the different meanings it assumed since its inception and evolution (Tansley and Tansley, 2012; Gallardo-Gallardo et al., 2013). Originally, it referred to personal characteristics (i.e., talent as object): those who possess, develop and use talents can rise above their peers in their specific fields of talent. A later meaning of the term referred to persons of talent (i.e., talent as subject/people) and is widely accepted nowadays as it frequently appears in jobs’ advertisements in relation to potential applicants (Gallardo-Gallardo et al. 2013).

The “talent as subject” approach can be either inclusive (i.e., understood to encompass all employees of an organization) or exclusive (i.e., covering an elite subset of an organization’s population) (Iles et al., 2010). The inclusive approach considers the term talent as everyone in the organization who possesses strength and whose successes can potentially create added value to it (Buckingham and Vosburgh, 2001). In contrast, the exclusive approach is based on the perception of workforce segmentation and considers talent as an elite division of the organization’s population (Tansley and Tansley, 2012). It includes talent as high performers and high potentials. “Talent as high performers” refers to a group of top-ranking employees (approx.10% in a specific area) in terms of capability and performance (Stahl et al., 2007; Ulrich and Smallwood, 2012) whereas “talents as high potentials” refers to a group of employees who demonstrate high levels of potential. Potential is defined as the possibility that individuals can become something more than what they currently are, implying further growth and development to reach some desired end state (Silzer et al., 2009). The exclusive approach is widely defended in the literature and is the most widespread approach to TM found in HR practice (Ready et al., 2010).

Talent Management Perspectives and Practices

Since there is no single consistent definition of TM, four main broad co-existing strands of thought have been identified for its conceptualization and contextualization (Ashton and Morton, 2012; McDonnell et al., 2012). They all generally share a prescriptive principle which is often found in the strategic management literature.

The first perspective views TM as a newer trend of HRM which primarily focuses on the “collection of typical HRM practices, functions or activities” (Lewis and Heckman, 2006). It claims that all employees have talents which should be explored for the organizational benefit through a range of HRM practices. This is considered as a universalist and inclusive approach to TM and has been criticized for being undifferentiated (Lewis and Heckman, 2006; Iles et al., 2010). The inclusive advocates will adopt a holistic approach by treating all employees equally on the assumption that they all contribute to the performance of the organization (Mensah, 2015).

The second perspective takes a narrow view of TM as a succession planning. A great emphasis is put on developing ‘talent pipelines’ to ensure the current and future supply of employees’ competencies as well as organization-wide talented mindsets (Lewis and Heckman, 2006). This perspective suggests a long-term and static view which assumes the continuity of roles and persons for the roles, enabling the planning and identification of the competencies required to successfully operate the business (Government of Western Australia, 2018).

The third approach considers TM as the management of talented employees. It focuses on only a relatively small proportion of the employees who demonstrate high potentials/performances (Michaels and Axelrod, 2001; Iles et al., 2010). Thus, firms adopting this approach tend to design distinctive HR activities including recruitments, trainings, developments and appraisals for this smallpool of talented employees.

The final perspective views TM as the strategic management of ‘pivotal positions’ rather than ‘pivotal people’. It indicates a departure from being people-oriented to position-oriented and from a micro focus on certain individuals to a more macro focus on systems (Jones et al., 2012). It concentrates on organizational processes and systems while identifying key positions that are strategically important to the organization and filling them with the right personnel through well-developed HR systems and processes (Boudreau and Ramstad, 2005; M.A. Huselid and Beatty, 2005; Collings and Mellahi, 2009).

Talent Management in the Banking Sector

One of the main elements that differentiate banks from other commercial organizations, is how they recognize and effectively manage talents (H. Nzewi and Ogbeta, 2015). Although employee attraction, recruitment and engagement play an important role in TM within banks, various other factors such as work-life balance, learning environment and succession planning, play an equally important role in capitalizing on talented employees retention for the banks’ advantage (Aizza et al., 2015).

Previously, banks used to focus mostly on accountants and commerce graduates to run their businesses. Nowadays there is a marked shift towards recruiting engineering and technology-oriented graduates (Shukla and Nayak, 2016). The evolution of digital banking has led to the development of certain key roles in the organization that require specific skill sets. This breed of employees possesses high responsiveness to technological advancement and other specific skill sets such as organizational agility, flexibility and adaptability. Besides, the transformation of banks to provide more value-added advisory services requires a talented workforce equipped with communication, advisory and negotiation skills with affinity to deep customer centrism and understanding (Goodspeed, 2016). This ensures the emergence of talent leadership that is critical to any organization’s prosperity (Chakrabarty, 2010).

Methodology

For the purpose of time saving and objective orientation, semi-structured interviews with open-ended questions were conducted.

Participants

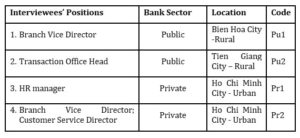

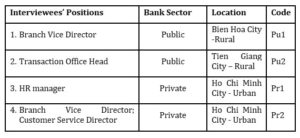

The purposive sampling and snowball techniques were applied by which the researchers approached two initial interviewees who assisted in gaining access to subsequent ones. The interviewees, consisting of four Vietnamese managers from four different banks (Table 1) that are representatives of the public and private sectors with over than 1,000 employees, formed this reported-on pilot study prior to rolling out a full-scale study (State Bank of Vietnam, 2018). The four selected managers, aged 35-40, included two branch vice directors (Pu1, Pr2); one transaction office head (Pu2) and one HR manager (Pr1) who has several years of experience in talent recruitment and development activities. The relatively young age range is commensurate with managerial positions that are open to the consideration of emerging issues such as TM. Furthermore, it is mostly likely that they had first-hand experiences as recipients of TM practices themselves (Cooke et al., 2014).

Table 1: Interviewees’ job positions and their bank types (created by authors)

Interview Procedure

The interviewees were contacted via phone and were sent an introductory letter and a participation consent form. A convenient meeting time and venue were then confirmed via phone and email. Each interview, which was audio-recorded with the interviewee’s permission, lasted for approx. 1 hour. It was later transcribed into a full and accurate word-for-word document rendition of the questions and answers (Rubin and Rubin, 2011). It was further translated into English with a validation review undertaken by an independent Vietnamese research assistant.

Interview Question Design

All interviewees were Vietnamese; therefore, in order to avoid any misunderstanding due to language barriers, the questions and the interview guide were translated into Vietnamese and double-checked for linguistic adjustments and rewording by a Vietnamese scholar. The interview questions which were prepared in advance to ensure consistency throughout all the interviews, were designed based on the research objectives as well as on previous qualitative studies on TM(Cooke et al., 2014; Kaewsaeng-on, 2016; Thunnissen and Buttiens, 2017).

Data Analysis

The qualitative analysis technique applied in this study was thematic analysis; a form of content analysis. It is usually associated with the considerable interpretation of latent content which is not easy to recognize and code by simply counting attributes (Braun, Virginia; Clarke, 2013). The thematic analysis involved basic steps including familiarizing the researchers with the data, generating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing, defining and naming themes and producing the report. Within each theme, the data from the public and private sectors was distinguishably analyzed then compared and contrasted.

Findings and Discussions

When being asked about consistency in the HRM or TM practice implementation among their bank branches, all interviewees insisted that all branches consistently followed the same direction and framework/policies regarding planned HRM programs. However, branch directors or direct managers can be limitedly flexible and creative in the way they conduct the practices. For example, they can invest more time and resources in improving the working environment and/or teamwork spirit or in providing additional mental support to talented employees.

Talent and Talent Management Conceptualization

- Talent is defined as the combination of soft skills, learning ability, flexibility and technology adaptability.

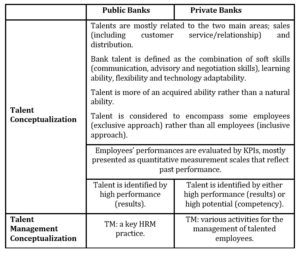

Respondents from both bank sectors (public and private) highlighted that talent in the banking industry is mostly related to two main areas; sales which includes customer service or customer relationship and distribution. When being asked about the qualities or features used to identify employees’ talents, the interviewees used different key terms to describe them.

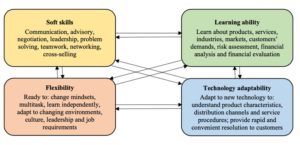

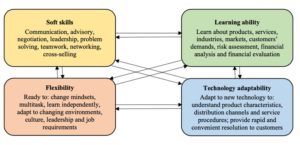

Based on the interconnections and relations between the Vietnamese terms stated by the interviewees and their corresponding frequency of use, four main classes containing the most prominent talent identifiers were synthesized; soft skills (such as communication, advisory, negotiation and problem solving skills, leadership, teamwork and cross-selling), learning ability, flexibility and technology adaptability (Fig. 1).

Fig.1: The interconnections between main factors contributing to bank talent

Respondent Pr1 in particular mentioned that talented candidates must have economic, financial or management background which provide them with the ability to evaluate business situations and analyze financial statements. Such abilities are highly important for sales staff and credit and customer relation executives to assess the economic conditions of customers, especially business customers and advise them throughout their business life cycle.

All interviewees believed that banks require their employees to develop a long-term bond with customers so that loyal customers would recommend the bank’s products and services to their friends and relatives. To achieve such snowballing sales strategy, it is essential for the bank staff to have strong soft skills such as communication, negotiation and advisory skills. They also need to have networking and teamwork abilities which enable them to widen their customers’ networks, develop an understanding of different industries or economic areas and support their colleagues to reach overall key performance indicators.

In terms of learning ability and as stated by interviewee Pr2, private banks have the tendency to recruit fresh candidates due to their willingness and eagerness to learn through different modalities such as reading books or communicating with experts, leaders and teammates. This would enable them to be equipped with sufficient knowledge for cross-selling and financial counselling. Private banks expect their talented employees to be willing to learn and progress rapidly in terms of such skills. The Pr1 underlined: “We want our salespersons to become long-term financial counsellors for customers, therefore, they should never stop learning. They need to grow with their customers and stay with them throughout the customers’ business journeys”.

As interviewees from both banking sectors were well aware of the fast changing banking environment, they understood that talented employees must be flexible and ready to change their mindsets to learn and adapt to environmental and organizational cultures and the varying job requirements. Specifically, flexibility enables employees to handle different multi-tasking jobs such as administration, counselling, advising and analyzing. In this context, most of the participants admitted that their HR systems have been transforming and even restructuring to some extent in order to accommodate such flexibility.

Markedly, the participants emphasized the ability of talented employees to keep abreast of technological changes in the current era of digital banking transformation. Delivery Service through online or mobile devices and the variety of banking services and transactions that customers can perform necessitate a rapid adaptability to new technological waves involving new products’ characteristics and a variety of distribution channels and service procedures. “Based on a good sense of technology, bank employees can deliver fast and convenient services with simple procedures to satisfy new generations of customers who require easy processes, quick resolutions and quick disbursements”, said the Pr1.

The interconnections between the above factors were depicted earlier and are consistent with findings in the literature (Chakrabarty, 2010; Institute of Bankers Malaysia, 2014; Ernst and Young, 2018; Ha and Nhan, 2019). For instance, good communication and teamwork skills would assist bank staff in developing their learning abilities. They can learn from their teammates, senior executives and their networks in order to acquire more knowledge about products, services, risk assessment, financial analysis, etc. Good learning ability enables them to assimilate and process information, hone confidence in communicating, express themselves and generally improve their soft skills. Such learning ability would also enhance their talents in adapting to new technological changes and in understanding the latest distribution channels and new service procedures. Understanding technology is essential for them to be successful sellers or customer relation executives who can guide and instruct customers to access online products/services or use intelligent mobile applications. Internally, they would be ready to flexibly adapt to changes related to bank operation processes, job requirements and leaders’ expectations. Flexibility is a highly important advantage as it allows bank staff to have open-mindsets and positive working attitudes which would in return support their soft skills, learning abilities and technology adaptability.

All respondents highlighted the importance to consider particular job positions for appropriate definitions of the talent. For instance, a credit officer needs to satisfy priority criteria related to risk control and risk assessmentInternal talents need to outweigh external ones regarding the understanding of the system and structure of banks. Talents chosen to fill leader positions must develop their leadership skills which can be developed via internal programs.

- Talent is more of an acquired ability rather than a natural one

Three out of the four respondents argued that talent should refer to abilities and skills acquired and developed through learning, experience and hard work rather than innate abilities. The nature of giftedness can act as a support but it is not a conditional prerequisite. The Pr2 interviewee emphasized that: “The nature of giftedness is not really necessary. During the working process, they must work hard. Because the results will firstly come from the efforts of each person not only in my field but in other fields as well. The nature of giftedness can support them but it is not the prerequisite condition. In the working process, the important things for employees are learning and improving themselves.” Although only one participant-Pu1 expressed that talent should always be considered as an innate construct since an example of talent in football was exemplified. Towards the end of the interview’s session, he mentioned that “The TM in this case is that through the working process, we can identify what are the strengths and weaknesses of our staff then we can allocate suitable tasks or encourage them to develop themselves”. Hence, it can be concluded that talent in banking industry is acquired through working experiences.

Markedly, participants Pu1 and Pu2 admitted that they had rarely heard of the term TM in the banking sector and did not have much knowledge about this issue. In contrast, respondents from the private banks appeared to be more confident about their understandings of talent. This is perhaps due to an adoption of special schemes and practices for recruiting and developing talented employees. It is debatable whether innate talent can be successful without being supplemented by motivation and training on particular activities (Ericsson et al., 1993; Abbott and Collins, 2004). If such talent exists, it probably would not be surprising that individuals who fulfill this criterion are hard to find in any walk of life and more so, within this domain of work (Kaewsaeng-on, 2016). Even in fields such as education, sports, music, etc., where the idea of talent is viewed as a natural ability, there is still a considerable debate and doubt about how it interacts with nurture (Vinkhuyzen et al., 2009; Meyers et al., 2013).

- Talent applies to high performers/potentials, not to all employees

All respondents highlighted talent, in banking terms, as applying to all high-performing/potential employees, specifically those possessing a combination of previously-mentioned capabilities such as soft skills, learning ability and adaptability and those who are perfectly matching the job specifications. TM is therefore more focused on employees who are highly qualified rather than those who are managed under the narrow notions of HRM practices. The interviewee Pu2 explained that “We have to manage by categorizing our staff into different groups. For instance, we may concentrate on about 4-5 special talents to help them develop and add value to the organizations… If we equalize them all, we will not discover who are the talented ones.” Furthermore, the consideration of talent as a high potential (competency) attribute normally applies to the case of fresh graduates; junior and newly-appointed staff. Those potential talents are given opportunities and are closely supported by leaders to improve even though their current performance results may not be satisfactory. The two respondents from the private banks admitted that they can be flexible in assessing their talented employees in certain situations by supplementing their appraisals with positive qualitative evaluation in order to impart more understanding and sympathy.

This finding is partially similar to that of (Athawale et al., 2013; Singh et al., 2013) which studied TM in the Indian banking sector and found that one of the differences between private and public banks in India is that talent in the private banking sector is identified by competency (high potential) whereas in the public banking sector it is identified by results (high performance).

All respondents underlined that employees in the banking sector are evaluated through Key Performance Indices (KPIs) mostly presented as quantitative measurement scales that reflect past performance. Therefore, talent in the banking field is normally linked to past performance results such as previous notable achievements or excellence rewards.

Through interviewee discussions, it was concluded that TM perceptions of the public banks’ respondents were similar to those of HRM in general. They identified TM as a key HRM practice. Interviewees from the two private banks defined TM as a combination of various activities for the management of talented employees including identification, attraction, development and retention of talents. They also underlined the need to build teams of talents within banks and used the “talent pool” expression in their explanations. In short, public bank managers did not express a clear understanding of TM concepts while those from the private sector were more confident about the articulation of what TM meant and the importance of it in ensuring business success. This can be reasoned by the fact that Vietnamese private banks adopted foreign TM schemes and models and exerted effort in standardizing their TM practices. This finding was supported in (Techcombank, 2017; N. Anh, 2018) by highlighting that Vietnamese private banks were more aware of the critical role of HRM in business competition and thereby invested resources in building and developing their talented labor forces. This finding is also similar to that in (Zhu and Verstraeten, 2013) which concluded that Vietnamese local private firms improved their HR practices rapidly and they are catching up with foreign-owned enterprises and joint ventures and exceeding those of state-owned enterprises.

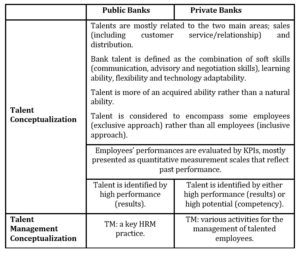

Comparison of Talent and TM Conceptualizations Between Public and Private Banks

According to (Singh et al., 2013; Prathiba and Balakrishnan, 2014; Aizza et al., 2015; Hitu, 2015), the TM scenario in the private banking sector appears to have notable differences from that in the public banking sector which may be due to their different management strategies and cultures. Based on the above analysis, the main differences and similarities between private banks and public banks regarding talent conceptualization and TM conceptualization can be summarized as in Table2.

Table 2: Comparison of talent and TM conceptualizations between public and private banks in Vietnam (created by authors)

Conclusions

The results of this study demonstrate that banking talent is defined as a combination of interconnected and interdependent soft skills (such as communication, advisory and negotiation skills), learning ability, flexibility and technology adaptability. Such abilities and skills can be acquired and developed by high performance/high potential employees through learning and experience which can be guided and supported by the banks’ TM strategies.

Next, talent in the private banking sector is identified by not only results (high performance) but also competency (high potential) whereas in the public banking sector it is mostly identified by results (high performance). Besides, the public banks’ respondents viewed TM as HRM practices in general.

It is recognized that this study has a number of limitations: (1) a four-sized sample; the researchers wish to expand this study in future based on a larger population sample, (2) cross-checking the findings of the study is not covered; its reliability and validity would be increased through methodological triangulation, usage of qualitative research methods and addition of other data collection techniquesand (3) absence of the perspectives of talented employees, high level managers and other stakeholders of the banks. Future research may solve the mentioned limitations and may also study this TM issue in another industry or in multi sectors to test the generalizability of the findings.

References

- Abbott, A. and Collins, D. (2004) ‘Eliminating the dichotomy between theory and practice in talent identification and development: Considering the role of psychology’, Journal of Sports Sciences, 22(5), 395–408. doi: 10.1080/02640410410001675324.

- Anh, N. (2018) ‘The hot issue of talent retention in banking sector’, Vietnambiz. [Online], [Retrieved 2018], https://vietnambiz.vn/nong-chuyen-thu-hut-va-giu-chan-nhan-su-ngan-hang-56691.htm

- Anwar, Aizza., Khan, Nadia Zubair Ahmad., & Sana, A. C. I. I. T. (2015) ‘Talent Management : Strategic Priority of Organizations’, IJIAS Journal, 9(July), 1148–1154. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/269039971.

- Al Ariss, A. et al. (2013) ‘Understanding career experiences of skilled minority ethnic workers in France and Germany’, International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(6), 1236–1256. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2012.709190.

- Ashton, C. and Morton, L. (2012) ‘Managing talent for competitive advantage: Taking a systemic approach to talent management’, Strategic HR Review, 4(5), 28–31. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/14754390580000819 Downloaded.

- Athawale, R. M., Todkar, R. V. and Ghansawant, R. S. (2013) ‘The need of talent management in public sector banks in India’, International Journal of Human Resource Management and Research, 3(5), 37–42.

- Boudreau, J. W. and Ramstad, P. M. (2005) ‘Talentship talent segmentation, and sustainability: A new hr decision science paradigm for a new strategy definition’, Human Resource Management, 44(2), 129–136. doi: 10.1002/hrm.20054.

- Braun, Virginia; Clarke, V. (2013) ‘Using thematic analysis in psychology’, Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling, 53(9), 1689–1699. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004.

- Buckingham, M. and Vosburgh, R. M. (2001) ‘The 21st century human resources function: It’s the talent, stupid!’, People and Strategy, 24(4), 17–24.

- Chakrabarty, K. C. (2010) ‘Deputy Governor of the Reserve Bank of India’, Address at the National Finance Conclave. [Online], [Retrieved 2018], https://www.rbi.org.in/scripts/BS_SpeechesView.aspx?id=538

- Chepkwony, N. K. (2012) ‘The link between talent management practices, succession planning and corporate strategy among commercial banks in Kenya’, School of business, [Online], [Retrieved 2018], http://erepository.uonbi.ac.ke/handle/11295/15855

- Collings, D. G. and Mellahi, K. (2009) ‘Strategic Talent Management: A review and research agenda’, Human Resource Management Review, 19(4), 304–313.

- Cooke, F. L., Saini, D. S. and Wang, J. (2014) ‘Talent management in China and India: A comparison of management perceptions and human resource practices’, Journal of World Business. Elsevier Inc., 49(2), 225–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jwb.2013.11.006.

- Ericsson, K. A. et al. (1993) ‘The Role of Deliberate Practice in the Acquisition of Expert Performance’, Psychological Review, 100(3), 363–406.

- Ernst and Young (2018) ‘The future of talent in banking: workforce evolution in the digital era’, Bank Governance Leadership Network. [Online], [Retrieved 2018],https://www.ey.com/Publication/vwLUAssets/ey-the-future-of-talent-in-banking/$File/ey-the-future-of-talent-in-banking.pdf.

- Froese, F. J., Vo, A. and Garrett, T. C. (2010) ‘Organizational Attractiveness of Foreign-Based Companies : A country of origin perspective’, International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 18(3), 271–281.

- Gallardo-Gallardo, E., Dries, N. and González-Cruz, T. F. (2013) ‘What is the meaning of “talent” in the world of work?’, Human Resource Management Review, 23(4), 290–300. doi: 10.1016/j.hrmr.2013.05.002.

- Goodspeed, T. O. (2016) ‘Untangling the Soft Skills Conversation’, The dialog.[Online], [Retrieved 2018], https://www.thedialogue.org/analysis/untangling-the-soft-skills-conversation/

- Government of Western Australia (2018) ‘Talent management and succession planning’, Government of Western Australia. [Online], [Retrieved 2018], https://www.jobsandskills.wa.gov.au/sites/default/files/uploads/documents/EMPLOYERS_section/jswa-emp-talent-management-succession-planning-brochure8.pdf

- Nzewi, O. C. and Ogbeta, M. (2015) ‘Talent Management and Employee Performance in Selected Commercial Banks in Asaba, Delta State, Nigeria’, European Journal of Business and Social Sciences, 4(9), 56–71.

- Ha, D. T. and Nhan, D. T. T. (2019) ‘Measuring Internal Factors Affecting the Competitiveness of Financial Companies : The Research Case in Vietnam’, in International Econometric Conference of Vietnam. Springer International Publishing, 596–605. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-04200-4.

- Hitu, M. (2015) ‘Talent Management Scenario in the Private and Public Sector Banking Industry’, SSRN 2600029, http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2600029.

- Iles, P., Preece, D. and Chuai, X. (2010) ‘Talent management as a management fashion in hrd: Towards a research agenda’, Human Resource Development International, 13(2), 125–145. doi: 10.1080/13678861003703666.

- Institute of Bankers Malaysia (2014) ‘Study on talent and skills requirements for the banking sector in Malaysia’. Institure of Bankers Malaysia. [Online], [Retrieved 2018], https://www.pwc.com/my/en/assets/publications/2014-ibbm-talent-and-skills-requirements-for-the-banking-sector-in-msia.pdf

- Jones, J. T. et al. (2012) ‘Talent management in practice in australia: Individualistic or strategic? An exploratory study’, Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 50(4), 399–420. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7941.2012.00036.x.

- Kaewsaeng-on, R. (2016)’Talent management: a critical investigation in the Thai hospitality industry’. The University of Salford. [Online], [Retrieved 2018], https://usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/39105/1/RudsadaKaewsaeng-on.pdf

- Kim, S., Froese, F. J. and Cox, A. (2012) ‘Applicant attraction to foreign companies: The case of Japanese companies in Vietnam’, Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 50(4), 439–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7941.2012.00038.x.

- Lewis, R. E. and Heckman, R. J. (2006) ‘Talent management: A critical review’, Human Resource Management Review, 16(2), 139–154. doi: 10.1016/j.hrmr.2006.03.001.

- A. Huselid, B. E. B. and Beatty, R. W. (2005) The Workforce Scorecard: Managing Human Capital to Execute Strategy. Harvard Business Review Press.

- Mawlawi, A. and Fawal, A. E. (2018) ‘Talent Management in the Lebanese banking sector’, Management, 8(3), 80–85.

- McDonnell, A., Collings, D. G. and Burgess, J. (2012) ‘Guest editors ’ note : Talent management in the Asia Pacific’, Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 50(4), 391–398. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7941.2012.00035.x.

- Mensah, J. K. (2015) ‘A “coalesced framework” of talent management and employee performance: For further research and practice’, International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 64(4), 544–566. doi: 10.1108/IJPPM-07-2014-0100.

- Meyers, M. C., van Woerkom, M. and Dries, N. (2013) ‘Talent – Innate or acquired? Theoretical considerations and their implications for talent management’, Human Resource Management Review. Elsevier Inc., 23(4), 305–321. doi: 10.1016/j.hrmr.2013.05.003.

- Michaels, E., Handfield-Jones, H. and Axelrod, B., (2001). The war for talent. Harvard Business Press.

- Nguyen, D. T. N., Teo, S. and Ho, M. (2018) ‘Development of human resource management in Vietnam: A semantic analysis’, Asia Pacific Journal of Management,35(1), 241–284. doi: 10.1007/s10490-017-9522-3.

- Ogbeta, M. E. (2015) ‘Talent management and employee performance in selected commercial banks in asaba, delta state, nigeria’, European Journal of Business and Social Sciences, 4(09), 56–71.

- Prathiba, S. and Balakrishnan, L. (2014) ‘A study on talent management strategies in private sector banks’, AMET International Journal of Management, 1(2), 33–40.

- Ready, D. A., Conger, J. A. and Hill, L. A. (2010) ‘Are You a High Potential ?’, Harvard Business Review, 88(6), 78–84.

- Rubin, H. J. and Rubin, I. S. (2011) Qualitative Interviewing: The Art of Hearing Data. Sage.

- Shukla, S. and Nayak, G. (2016) ‘Banks now bet on young and technology-savvy talent with special ‘skill sets’’, The Economic Times. [Online], [Retrieved 2018], https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/banking/finance/banking/banks-now-bet-on-young-and-technology-savvy-talent-with-special-skill-sets/articleshow/50714117.cms?from=mdr

- Silzer, R. O. B., Church, A. H. and Holmes, O. W. (2009) ‘The Pearls and Perils of’, industrialandOrganizationalPsychology, 2, 377–412.

- Singh, S. et al. (2013) ‘Talent Management Scenario in the Banking Industry Keywords : Talent Management , Talent Acquisition , Retention Strategies , Talent Retention .’, Paripex – Indian Journal of Research, 2(4), 274–276.

- Stahl, G. K. and I. Björkman, E. Farndale, S.S. Morris, J. Paauwe, P. Stiles, J. T. and P. M. W. (2007) ‘Global talent management: How leading multinationals build and sustain their talent pipeline’, Fontainebleau: INSEAD, 24.

- State Bank of Vietnam (2012) ‘Policies about human resources development in the banking sector from 2011 to 2020’. GSO Vietnam. [Online], [Retrieved 2018], https://www.gso.gov.vn/Modules/DeedDownload.aspx?DeedID=55

- State Bank of Vietnam (2018) ‘List of commercial banks in Vietnam’, State Bank of Vietnam. [Online], [Retrieved 2018], https://sbv.gov.vn/webcenter/portal/vi/menu/fm/htctctd/nh/nhtm/nhtmcp?_afrLoop=29986636766083095#%40%3F_afrLoop%3D29986636766083095%26centerWidth%3D80%2525%26leftWidth%3D20%2525%26rightWidth%3D0%2525%26showFooter%3Dfalse%26showHeader%3Dfalse%26_adf.ctrl-state%3D16fptoa5r1_4

- Tansley, C. and Tansley, C. (2012) ‘What do we mean by the term “talent” in talent management?’, Industrial and Commercial Training, 43(5), 266–274. doi: 10.1108/00197851111145853.

- Techcombank (2017)’Quality HR resources help banks to sustainably develop’,Techcombank. [Online], [Retrieved 2018], https://sbv.gov.vn/webcenter/portal/vi/menu/fm/htctctd/nh/nhtm/nhtmcp?_afrLoop=29986636766083095#%40%3F_afrLoop%3D29986636766083095%26centerWidth%3D80%2525%26leftWidth%3D20%2525%26rightWidth%3D0%2525%26showFooter%3Dfalse%26showHeader%3Dfalse%26_adf.ctrl-state%3D16fptoa5r1_4

- Thunnissen, M. and Buttiens, D. (2017) ‘Talent Management in Public Sector Organizations: A Study on the Impact of Contextual Factors on the TM Approach in Flemish and Dutch Public Sector Organizations’, Public Personnel Management, 46(4), 391–418. doi: 10.1177/0091026017721570.

- Tran, L. V. and Vu, T. T. (2015) ‘Human resource in Vietnam banking system restructuring’, Scientific Research, 7, 90–98.

- Ulrich, D. and Smallwood, N. (2012) ‘What is talent?’, Leader to Leader, 2012, 55–61. doi: 10.1002/ltl.20011.

- Vinkhuyzen, A. A. E. et al. (2009) ‘The heritability of aptitude and exceptional talent across different domains in adolescents and young adults’, Behavior Genetics, 39(4), 380–392. doi: 10.1007/s10519-009-9260-5.

- Zhu, Y. and Verstraeten, M. (2013) ‘Human resource management practices with vietnamese characteristics: A study of managers’ responses’, Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 51(2), 152–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7941.2012.00057.x.