Introduction

The aspects of teamwork constitute an object of scientific interest for many researchers. This subject gains particular importance in modern times, when in connection with progressing globalization, people’s increased mobility and the development of technology, creating teams consisting of representatives of many cultures is becoming more and more common. The formation of multicultural teams in a rapidly changing work environment poses new challenges for both managers (leaders) and employees (team members). Therefore, the role of leaders in managing multicultural teams gains significance, as they have to effectively deal with emerging issues resulting from the diversity of cultures (Matveev and Milter, 2004).

There are many problems associated with multiculturalism, including different languages, religions as well as ways of thinking and perceiving reality. However, it should be noted that the ability to manage cultural diversity can provide many benefits to the organization and its members (Giedraitis et al., 2017; Kopertyńska, 2018). Multicultural teams have a definite advantage over monocultural ones, as their members have diverse experiences and different worldviews, which translates into generating a variety of solutions to the analyzed problems (Kuc and Żemigała, 2010).

The aim of this article is to identify differences in the perception of challenges and benefits of working in multicultural teams as perceived by young people (students) from Poland and Romania.

Working in multicultural teams – theoretical background

In the literature, a team is defined as a collective of people who interact regularly in pursuit of set common goals (Katzembach and Smith, 1992). Multicultural teams are task-oriented groups consisting of individuals with different cultural backgrounds (Marquardt and Horvath, 2001). They are interdependent in carrying out their tasks, sharing responsibility for the team’s results (Halverson and Tirmizi, 2008).

Multicultural teams are perceived as an asset to the organization (Williams and O’Reilly, 1998; Stahl et al., 2010). Cultural diversity does not negatively impact team performance (Brannen and Salk, 2000). Multicultural teams are dominated by different perspectives on a particular issue, diverse experiences, different problem-solving and decision-making styles, and smart ideas (Adler, 2002). Therefore, multicultural teams are a key element of organizational structures of both multinational corporations as well as small and medium enterprises (Donnellon, 2006).

The functioning of multicultural teams has many benefits, but it also requires overcoming many difficulties. As past research indicates, because of their diversity, multicultural teams are prone to difficulties including language barriers, misunderstandings, ineffective communication, and differences in communication styles (Mäkilouko, 2004; Adler, 2002; Ramthun and Matkin, 2012; Aritz and Walker, 2014; Hall, 2001; Lisak and Erez, 2015; Sogancilar and Ors, 2018; Szymczak, 2018; Behfar et al., 2006; Szydło et al., 2020). Problems with pronunciation and language fluency create major communication barriers (Matveev and Milter, 2004). Also, work styles and expectations, which vary from culture to culture, can pose difficulties in mutual work (Sogancilar and Ors, 2018; Hall, 2003). A hypothetical lack of acceptance due to the leader’s gender, for example, can also create problems (Hall, 2001). Another aspect is stereotypes and prejudices that cause selective reception of information that exists in the social environment, and simplify views of the world (Sasińska-Klas, 2010). Cultural differences can also undermine the development of group norms (Behfar et al., 2006; Ely and Thomas, 2001; Jehn et al., 1999) and generate conflicts (Kirchmeyer and Cohen, 1992; De Dreu and Weingart, 2003; Kiryluk et al., 2020). There also emerge challenges and difficulties associated with virtual teamwork (Samul et al., 2020; Oertig and Buergi, 2006; Heimer and Vince, 1998; Jarvenpaa and Leidner, 1999).

Multicultural teams bringing together representatives of different nationalities differ from monocultural teams in many respects. The type and scale of problems is different, and so are the ways of solving them effectively (Gadomska-Lila et al., 2011). A multicultural team leader must possess a set of qualities necessary to lead people, such as tolerance, respect, empathy, openness, goal orientation (Kożusznik, 2005). Other important aspects are orientation to development, prospective attitude to the future, encouraging team members to cooperate, getting to know the values and needs of employees, creating an atmosphere of cooperation based on mutual respect, developing knowledge about cultural differences and respecting them, the ability to perceive cultural problems, the ability to overcome cultural stereotypes, as well as developing cultural intelligence (Stańda, 2003; Adamonienė et al., 2021; Piotrowski and Świątkowski, 2000; Burakova and Filbien, 2020; Szpilko, Szydło and Winkowska, 2020; Matveev, 2017; Higgs, 1996; Szydło and Grześ, 2020; Rozkwitalska, 2012; Jesevičiūtė-Ufartienė, Brusokaitė and Widelska, 2020). A leader cannot classify people into his/her own group or a foreign group (Tajfel and Turner, 1986; Pettigrew, 2001; Brewer and Miller, 1996). He/she should set a benchmark for addressing diversity through an open approach, focused on mutual learning and deriving advantage from observed differences. A leader, in accepting diversity, should create an environment that allows team members to appreciate each other’s views. This improves team performance (Sogancilar and Ors, 2018).

Research Methodology

The study was conducted using the method of the diagnostic survey with the CAWI (Computer-Assisted Web Interview) technique. The time frame spanned over the period between January and April 2019, and the location covered two countries: Poland and Romania. A total of 2,100 correctly completed questionnaires were obtained: 1,121 from Bialystok University of Technology in Poland (53.4% of all respondents) and 979 from the Babes-Bolyai University in the Romania (46.6%). The Polish group of respondents was composed of 51.7% women and 48.3% men. The respondents from Romania consisted of 24.1% women and 75.9% men.

The following research problems were formulated:

- What are the differences between the Polish and Romanian respondents in the perception of skills and competencies necessary to work in multicultural teams?

- What differences exist among the Polish and Romanian male and female respondents in the perception of difficulties connected with working in multicultural teams?

- What are the differences among male and female respondents from Poland and Romania in perceived benefits of working in multicultural teams?

The survey form contained 16 questions. This article presents only a part of the obtained results, i.e. those related to the analysed subject. A survey questionnaire prepared in the native languages of participating students was the tool used to carry out the study. The obtained data were subject to statistical analysis using Statistical 13.3 software.

Research Results

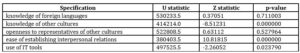

Cooperation in multicultural teams requires various skills and competencies. In the present research, they are examined from the point of view of the Polish and Romanian respondents in relation to five aspects: knowledge of foreign languages, knowledge about other cultures, openness to representatives of other cultures, ease of establishing interpersonal relations and using IT tools.

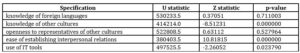

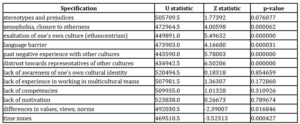

There were statistically significant differences (p<0.05) between the answers provided by the Polish and Romanian respondents in three out of five analysed aspects. They concerned knowledge about other cultures (p=0.000000), ease of establishing interpersonal relations (p=0.000000) and using IT tools (p=0.023790) (Table 1).

Table 1: Differences in skills and competencies necessary to work in multicultural teams in the opinion of Polish and Romanian respondents – Mann-Whitney U test results

Source: based on (Szydło et al., 2020).

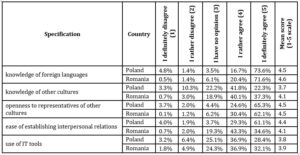

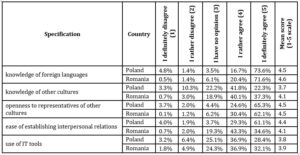

Students from both researched countries considered the knowledge of foreign languages (the average score for Romania – 4.6, Poland – 4.5) and openness to representatives of other cultures (in both cases the average score was 4.5) as the most important factors while working in multicultural teams. In the opinion of 91% of both Poles and Romanians, knowledge of foreign languages definitely facilitates cooperation in a multicultural team (Table 2).

Table 2: Skills and competencies necessary to work in multicultural teams in the opinion of Polish and Romanian respondent

Source: based on (Szydło et al., 2020).

Statistically significant differences were observed in the case of the respondents’ opinions with regard to other assessed skills and competencies. The Romanian respondents (mean score of 4.1) value knowledge about other cultures more highly than the Poles (mean score of 3.7) when working in multicultural teams. On the other hand, Polish respondents (mean score of 4.4) value higher the ease of establishing interpersonal relations than Romanians (mean score of 4.1). The ability to use IT tools is slightly less important for cooperation in multicultural teams according to both Polish (mean score of 3.8) and Romanian (mean score of 3.9) respondents. A detailed distribution of answers is presented in Table 2.

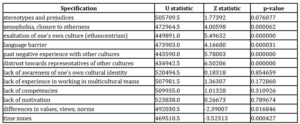

Working in multicultural teams is often associated with various difficulties. In the case of seven out of twelve analysed variables, statistically significant differences (p<0.05) were observed between the Polish and Romanian participants, concerning: xenophobia and closure to otherness (p=0.000062), exaltation of own culture (p=0.000000), language barrier (p=0.000031), past negative experiences with other cultures (p=0.000000), distrust towards representatives of other cultures (p=0.000000), differences in values, views, norms (p=0.016846), and time zones (p=0.000427). No differences in the opinions were identified with regard to stereotypes and prejudices, level of awareness of cultural identity, experience of working in multicultural teams, competence and motivation (Table 3).

Table 3: Differences in perceived difficulties of working in multicultural teams between Polish and Romanian respondents – Mann-Whitney U test results

Source: based on (Szydło et al., 2020).

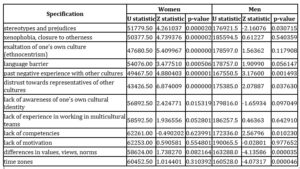

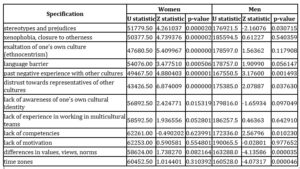

More detailed analyses indicate that there exist differences in the opinions of the Polish and Romanian respondents depending on their gender. In the case of three out of twelve analysed variables, statistically significant differences (p<0.05) were noted in the opinions of Polish and Romanian men and women in the following aspects: stereotypes and prejudices (women p=0.000020, men p=0.030715), past negative experience with other cultures (women p=0.000001, men p=0.001493), and distrust towards representatives of other cultures (women p=0.000000, men p=0.037630). Additionally, as far as the difficulties connected with working in multicultural teams are concerned, statistically significant differences were noted in the opinions of Polish and Romanian women, concerning: xenophobia and closure to otherness (p=0.000002), exalting of one’s own culture (p=0.000000), language barrier (p=0.000506), and awareness of one’s own cultural identity (p=0.015319). In the case of Polish and Romanian men, their opinions were also statistically significantly different in relation to: competence (p=0.010230), values, views and norms (p=0.000035) and time zones (p=0.000046) (Table 4).

Table 4: Differences in perceived difficulties of working in multicultural teams among Polish and Romanian men and women – Mann-Whitney U test results

Both Polish (mean 4.1) and Romanian (mean 4.0) respondents considered language barriers as the most important difficulty while working in multicultural teams. It should be noted, however, that both Polish (mean 4.0) and Romanian (mean 4.0) men considered it as the most significant barrier to working in multicultural teams. The same opinion was expressed by female respondents, where Polish women (mean score of 4.2) considered the language barrier as a more important obstacle to working in multicultural teams than Romanian women (mean score of 3.9).

Next, respondents from Poland and Romania considered stereotypes and prejudice, xenophobia and closure to otherness as a very important obstacle in multicultural teams. It should be noted here that women from Poland (mean score of 4.1) perceive stereotypes and prejudices as a barrier to work in multicultural teams more than women from Romania (mean score of 3.8), as well as men from Poland (mean score of 3.9), and even more as compared to men from Romania (mean score of 3.7). Opinions are similar with respect to xenophobia. Polish women (mean score of 4.1) perceive it as a more serious obstacle to contacts with people from other cultures than Romanian women (mean score of 3.8) as well as Polish (mean score of 3.9) and Romanian men (mean score of 3.9). Also, Polish women (mean 4.0) perceive ethnocentrism as a greater impediment to multicultural cooperation than Romanian women (mean 3.6) and Romanian men (mean 3.7) as well as Polish men (mean 3.8).

Lack of motivation should also be considered as a significant obstacle in the work of multicultural teams, which was rated at the same level by both Polish (mean 3.8) and Romanian (mean 3.8) respondents. Also distrust towards representatives of other cultures is a definite obstacle in undertaking common activities. It should be noted here that Polish women (mean score of 3.9) perceive its negative impact on working in multicultural teams more than Romanian women (mean score of 3.4) as well as Romanian (mean score of 3.6) and Polish men (mean score of 3.7). Similarly, past negative experience with other cultures according to women (mean 3.7) and men (mean 3.6) from Poland make it more difficult to work in multicultural teams than according to women (mean 3.3) and men (mean 3.4) from Romania. According to the Romanian respondents, pejorative experiences from the past are not so important in building multicultural relations.

According to the respondents, issues related to values, views and norms as well as competencies are not very significant barriers. It should be noted, however, that issues related to values and views are more important barriers for Romanian men (mean score of 3.7) and Polish women (mean score of 3.6) than Romanian women (mean score of 3.5) and Polish men (mean score of 3.4).

Issues related to the awareness of one’s own cultural identity, as well as experience in working in multicultural teams in the opinion of the respondents are also not a very important determinant of multicultural teamwork. It should be noted, however, that the issues related to cultural identity are a more significant barrier for Polish women (mean score of 3.3) and Romanian men (mean score of 3.2) than for Romanian women (mean score of 3.1) and Polish men (mean score of 3.1). On the other hand, the functioning of the team in different time zones is perceived by the respondents as the least significant barrier both for Poles and Romanians. A detailed percentage distribution of answers and evaluations of Polish and Romanian respondents (including a breakdown by gender) is presented in Table 5.

Table 5: Difficulties related to working in multicultural teams according to Polish and

Romanian respondents (by gender)

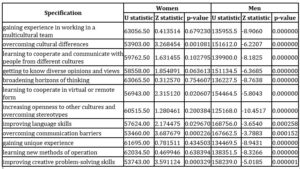

Working in a team consisting of people from different cultures provides various benefits. Statistically significant differences (p<0.05) between responses of Polish and Romanian interviewees were observed in the case of nine out of twelve statements, which concerned: gaining experience in working in a multicultural team (p=0.000000), overcoming cultural differences (p=0.032727), learning to cooperate and communicate with people from different cultures (p=0. 000000), learning about diverse opinions and views (p=0.001300), broadening the horizons of thinking (0.000000), learning to cooperate in virtual or remote form (p=0.001171), increasing openness to other cultures and breaking stereotypes (p=0.000000), gaining unique experience (p=0.000000), and learning new methods of operation (p=0.000000). There were no differences between the opinions of Polish and Romanian respondents in terms of improving language skills, overcoming communication barriers and improving creative problem-solving skills (Table 6).

Table 6: Differences in perceiving the benefits of working in multicultural teams in the opinions of Polish and Romanian respondents – Mann-Whitney U test results

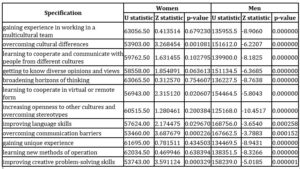

More detailed analyses indicate that there exist differences in the opinions of Polish and Romanian respondents depending on their gender. In the case of five out of twelve analysed variables, statistically significant differences (p<0.05) were found in the opinion of Polish and Romanian men and women in the following aspects: overcoming cultural differences (women p=0.001081, men p=0.000000), learning to cooperate in virtual or remote form (women p=0. 020607, men p=0.000000), improving language skills (women p=0.029670, men p=0.000258), overcoming communication barriers (women p=0.000226, men p=0.000152) and improving creative problem-solving skills (women p=0.000329, men p=0.000001). It should also be noted that in the case of male interviewees, statistically significant differences were noted in all twelve assessed categories in relation to Poland and Romania (Table 7).

Table 7: Differences in perceiving the benefits of working in multicultural teams in the opinions of men and women from Poland and Romania – Mann-Whitney U test results

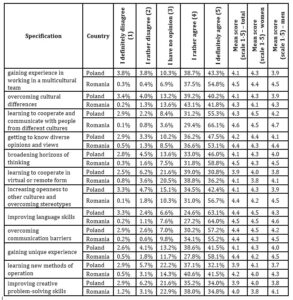

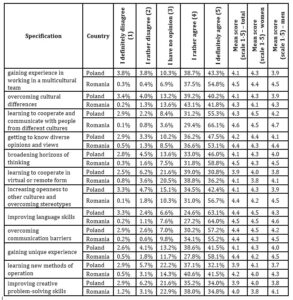

Both Polish and Romanian respondents recognized learning to cooperate and communicate with people from different cultures, as well as improving language skills as the most important benefits of working in multicultural teams. It is of note that increasing cooperation and communication skills in multicultural teams is a more important benefit in the opinion of Romanian men (mean score of 4.7), than Polish (mean score of 4.5) and Romanian women (mean score of 4.5), and even more so than Polish men (4.2). On the other hand, the opportunity to improve language skills is definitely a greater benefit of cooperation with representatives of other cultures for Romanian men (mean score of 4.6) than Polish women (mean score of 4.5) and Romanian women (mean score of 4.5), and even more so than Polish men (4.3) (Table 8).

Table 8: Benefits of working in multicultural teams according to Polish and

Romanian respondents (by gender)

Breaking down communication barriers is also considered as an important benefit by the respondents, which is a greater benefit of working in multicultural teams for Polish women (mean 4.5) and Romanian men (mean 4.5) than for Romanian women (mean 4.3) and Polish men (mean 4.2). Also important for the respondents are issues related to gaining experience in working in a multicultural team (Romanian mean – 4.5, Polish – 4.1) and broadening their horizons (Romanian average – 4.5, Polish – 4.1). Working with representatives of other cultures makes it possible to perceive the world not only through the prism of one’s own culture, which in time shapes the ability to see and appreciate other points of view. At the same time, it should be noted that these benefits are much more appreciated by men and women from Romania than by men and women from Poland.

The situation is quite similar when it comes to getting to know diverse opinions and views (mean score for Romania – 4.4, Poland – 4.2), increasing openness to other cultures and overcoming stereotypes (mean score for Romania – 4.4, Poland – 4.1), gaining unique experience (mean score for Romania – 4.4, Poland – 4.1), and overcoming cultural differences (mean score for Romania – 4.3, Poland – 4.1). Cooperation in a multicultural team increases openness towards different customs, positively shapes attitudes to other cultures, and surpasses conventional thinking and acting. It also enables to break down cultural and communication barriers. It should be noted that improvement in this area is more appreciated by Romanian men and Polish women than Romanian women, and even more so than by Polish men.

The least important benefits of working in multicultural teams were considered in the possibility to learn new methods of operation (Romanian mean – 4.2, Polish – 3.9), learning to cooperate in a virtual or remote form (mean score for Romania – 4.1, Poland – 3.9), and improving creative problem-solving skills (Romanian mean – 4.0, Polish – 3.9). It is worth mentioning that Romanian men and Polish women perceive bigger benefits than Romanian women and Polish men with respect to these issues (Table 8).

Conclusions

Summarizing the results obtained in the framework of the conducted research, it should be first of all noticed that students from both Poland and Romania considered the knowledge of foreign languages and openness to representatives of other cultures as the most important factors while working in multicultural teams.

Both the male and female respondents from Poland and Romania considered language barriers as the key difficulty in working in multicultural teams. However, women from Poland considered the inability to use foreign languages as a more important obstacle to cooperation in multicultural teams than other groups of respondents. Also, the respondents from Poland and Romania considered stereotypes and prejudice, xenophobia and closure to otherness as well as ethnocentrism as very important obstacles in their work. It should be noted here that women from Poland perceive the indicated aspects as a more serious problem in the work of multicultural team than women from Romania, as well as men from both these countries. Other analysed aspects, such as lack of motivation, distrust towards representatives of other cultures, past negative experience, lack of competence and values, views and norms are less important difficulties in working in multicultural teams.

Despite many barriers, working in multicultural teams brings many benefits. The main benefits of working in such teams are learning how to cooperate and communicate with people from different cultures and the possibility to improve language skills. It should be noted that these benefits are more important in the opinion of men from Romania than other respondents. As important benefits, respondents also indicated breaking down communication barriers, gaining experience in working in a multicultural team and broadening their horizons.

After analysing the obtained results it can be concluded that one of the tools increasing effective work of multicultural teams will be first of all trainings in language competence and cultural awareness. Thanks to training courses aimed at developing intercultural competencies, team members will be able to become aware of differences and similarities between them and prevent misunderstandings in the future. This type of training will also contribute to building trust, leading to an open and relaxed atmosphere within the group. It is important that the team is characterized by good relations and openness to other cultures (Szydło and Widelska, 2018).

The obtained results are a contribution to further in-depth research and analysis regarding work in a culturally diverse environment. Therefore, it is worth extending them to other age groups in the future, especially among people actively functioning on the labour market. The comparison of opinions obtained from students with the views of working people may provide valuable information about differences in the perception of work in multicultural teams as well as related problems and needs. This information may be useful in creating teams consisting of representatives of Polish and Romanian cultures, as well as in choosing the scope of training for future and current members of culturally diversified teams. Further research should also take into account the use of foresight methods (Ejdys et al., 2017, 2019; Kononiuk and Pająk, 2019; Szpilko, 2014, 2016), which will allow to build a vision of the future and foster the development of multicultural teams in organizations.

Acknowledgment

The project is financed by the Polish National Agency for Academic Exchange as part of the International Academic Partnerships (project PPI/APM/2018/1/00033/U/001).

Copyright Notice

Authors who publish in any IBIMA Publishing open access journal retain the copyright of their work under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License, which allows the unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction of an article in any medium, provided that the original work is properly cited. No permission is required from the authors or the publishers. While authors retain copyright of their work with first publication rights granted to IBIMA Publishing, authors are required to transfer copyrights associated with commercial use to this Publisher. Revenues produced from commercial sales and distribution of published articles are used to maintain reduced publication fees and charges

References

- Adamonienė, R., Litavniece, L., Ruibytė, L. and Viduolienė, E. (2021), ‘Influence of individual and organisational variables on the perception of organisational values’, Engineering Management in Production and Services, 13 (2), 7-17.

- Adler, N.J. (2002), ‘International dimensions of organizational behavior’, Southwestern, Cincinnati.

- Aritz, J. and Walker, R.C. (2014), ‘Leadership styles in multicultural groups: Americans and East Asians working together’, International Journal of Business Communication, 51 (1), 72-92.

- Behfar, K., Kern, M. and Brett, J. (2006), ‘Managing challenges in multicultural teams, National culture and groups’, Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Brannen, M.Y. and Salk, J.E. (2000), ‘Partnering across borders: Negotiating organizational culturein a German-Japanese joint venture’, Human relations, 53 (4), 451-487.

- Brewer, M. B. and Miller, N. (1996), ‘Intergroup relations’, Open University Press, Buckingham.

- Burakova, M. and Filbien, M. (2020), ‘Cultural intelligence as a predictor of job performance in expatriation: The mediation role of cross-cultural adjustment’, Pratiques Psychologiques, 26 (1), 1-17.

- De Dreu, C.K.W. and Weingart, L.R. (2003), ‘Task versus relationship conflict, team performance, and team member satisfaction: ameta-analysis’, Journal of Applied Psychology, 88 (4), 741-749.

- Donnellon, A. (2006), ‘Leading teams: expert solutions to everyday challenges’, Harvard Business Review.

- Ejdys, J., Gudanowska, A., Halicka, K., Kononiuk, A., Magruk, A., Nazarko, J., Nazarko, Ł., Szpilko, D. and Widelska, U. (2019), ‘Foresight in Higher Education Institutions: Evidence from Poland’, Foresight and STI Governance, 13, 77-89.

- Ejdys, J., Halicka, K., Nazarko, Ł., Kononiuk, A., Olszewska, A. M. and Nazarko, J. (2017), ‘Factor analysis as a tool supporting STEEPVL approach to the identification of driving forces of technological innovation’, Procedia Engineering, 182, 491-496.

- Ely, R.J. and Thomas, D.A. (2001). ‘Cultural diversity at work: the effects of diversity perspectives on work group processes and outcomes’, Administrative Science Quarterly, 46 (2), 229-273.

- Gadomska-Lila, K., Rudawska, A. and Moszoro, B. (2011), ‘Rola lidera w zespołach wielokulturowych [The role of the leader in multicultural teams]’, Przedsiębiorczość i Zarządzanie, XII (4), 7-20.

- Giedraitis, A., Stašys, R. and Skirpstaitė, R. (2017), ‘Management team development opportunities: A case of lithuanian furniture company’, Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues, 5 (2), 212-222.

- Hall, E.T. (2001), ‘Poza kulturą [Beyond culture]’, PWN, Warszawa.

- Hall, E.T. (2003), ‘Ukryty wymiar [Hidden dimension]’, Muza, Warszawa.

- Halverson, C.B. and Tirmizi, S.A. (eds), (2008), ‘Effective multicultural teams: theory and practice’, Springer Science & Business Media.

- Heimer, C. and Vince, R. (1998), ‘Sustainable learning and change in international teams: from imperceptible behavior to rigorous practice’, Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 19 (2), 83-88.

- Higgs, M. (1996), ‘Overcoming the problems of cultural differences to establish success for international management teams’, Team Performance Management: An International Journal, 1 (2), 36-43.

- Jarvenpaa, S.L. and Leidner, D.E. (1999), ‘Communication and trust in global virtual teams’, Organizational Science, 10 (6), 791-816.

- Jehn, K.A., Northcraft, G.B. and Neale, M.A. (1999), ‘Why differences make a difference: afield study of diversity, conflict and performance in workgroups’, Administrative Science Quarterly, 44 (4), 741-763.

- Jesevičiūtė-Ufartienė, L., Brusokaitė, G. and Widelska, U. (2020), ‘Relationship between organisational silence and employee demographic characteristics: the case of Lithuanian teachers’, Engineering Management in Production and Services, 12 (3), 18-27.

- Katzenbach, J.R. and Smith, D. (1992), ‘The Wisdom of Teams: Creating the High-Performance Organization’, Harvard Business Press.

- Kirchmeyer, C. and Cohen, A. (1992), ‘Multicultural groups: their performance and reactions with constructive conflict’, Group & Organization Management, 17 (2), 153-170.

- Kiryluk, H., Glińska, E. and Barkun, Y. (2020), ‘Benefits and barriers to cooperation in the process of building a place’s brand: perspective of tourist region stakeholders in Poland’, Oeconomia Copernicana, 11 (2), 289-307.

- Kononiuk, A., and Pająk, A. (eds), (2019), ‘Projektowanie kariery zawodowej – perspektywa badań foresightowych [Designing careers – a foresight perspective foresight studies]’, Publishing House of Bialystok University of Technology, Białystok.

- Kopertyńska, M.W. (2018), ‘Funkcjonowanie zespołów kulturowych w przedsiębiorstwach – doświadczenia badawcze [The functioning of cultural teams in enterprises – research experiences]’, Management Forum, 6 (2),16-22.

- Kożusznik, B. (2005), ‘Kierowanie zespołem pracowniczym [Management of the work team]’, PWE, Warszawa.

- Kuc, B. and Żemigała, M. (2010), ‘Menedżer nowych czasów. Najlepsze metody i narzędzia zarządzania [The manager of new times. The best management methods and tools]’, Wydawnictwo Onepress, Gliwice.

- Lisak, A. and Erez, M. (2015), ‘Leadership emergence in multicultural teams: the power of global characteristics’, Journal of World Business, 50 (1), 3-14.

- Mäkilouko, M. (2004), ‘Coping with multicultural projects: the leadership styles of Finnish project managers’, International Journal of Project Management, 22 (5), 387-396.

- Marquardt, M. and Horvath, L. (2001), ‘Global teams: how top multinationals span boundaries and cultures with high-speed teamwork’, Davies-Black Publishing, Palo Alto.

- Matveev, A. (2017), Intercultural Competence in Organizations: A Guide for Leaders, Educators and Team Players, Springer, Switzerland.

- Matveev, A.V. and Milter, R.G. (2004), ‘The value of intercultural competence for performance of multicultural teams’, Team Performance Management, 10 (5/6), 104-111.

- Oertig, M. and Buergi, T. (2006), ‘The challenges of managing cross-cultural virtual project teams’, Team Performance Management: An International Journal, 12 (1/2), 23-30.

- Pettigrew, T. (2001), ‘The ultimate attribution error: Extending Allport’s cognitive analysis of prejudice’, Intergroup relations: Essential readings, Hogg, M. A. and Abrams D., Psychology Press, New York.

- Piotrowski, K. and Świątkowski, M. (2000), ‘Kierowanie zespołami ludzi [Managing teams of people]’, Dom Wydawniczy Bellona, Warszawa.

- Ramthun, A.J. and Matkin, G.S. (2012), ‘Multicultural shared leadership: a conceptual model of shared leadership in culturally diverse teams’, Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 19 (3), 303-314.

- Rozkwitalska, M. (2012), ‘Human Resource Management strategies for overcoming the barriers in crossborder acquisitions of Multinational Companies: the case of multinational subsidiaries in Poland’, Social Sciences, 3 (77), 77-87.

- Samul, J., Zaharie, M., Pawluczuk, A. and Petre, A. (2020), ‘Leading and developing virtual teams: practical lessons learned from university students’, Publishing House of Bialystok University of Technology, Białystok.

- Sasińka-Klas, T. (2010), ‘Stereotypy i ich odzwierciedlenie w opinii publicznej [Stereotypes and their reflection in public opinion]’, Mity i stereotypy w polityce. Przeszłość i teraźniejszość [Myths and stereotypes in politics. Past and present], Kosińska-Metryka, A. and Gołaś, M. (ed), Wydawnictwo Adam Marszałek, Toruń.

- Stahl, G.K., Maznevski, M., Voigt, A. and Jonsen, K. (2010), ‘Unraveling the effects of cultural diversity in teams: ameta-analysis of research on multicultural work groups’, Journal of International Business Studies, 41, 690-709.

- Stańda, (2003), ‘Przywództwo kierownicze w wymiarze kultury organizacyjnej [Managerial leadership in the organisational culture dimension]’, Zeszyty Naukowe Akademii Ekonomicznej w Poznaniu, 36, pp. 314-319.

- Szpilko, D., Szydło, J. and Winkowska, J. (2020), ‘Social Participation of City Inhabitants Versus Their Future Orientation. Evidence From Poland’, WSEAS Transactions on Business and Economics, 17, 692-702.

- Szydło, J. and Grześ-Bukłaho, J. (2020), ‘Relations between National and Organisational Culture – Case Study’, Sustainability, 12 (4), 1-22.

- Szydło, J. and Widelska, U. (2018), ‘Leadership values – the perspective of potential managers from Poland and Ukraine (comparative analysis)’, Business and Management 2018: The 10th International Scientific Conference, Vilnius, Lithuania.

- Szydło, J., Szpilko, D., Rus, C. and Osoian, C. (2020), ‘Management of muliticultural teams: practical lessons learned from university students’, Publishing House of Bialystok University of Technology, Białystok.

- Szpilko, D. (2014), ‘The methods used in the construction of a tourism development strategy in the regions. A case study of Poland’, Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences¸ 156, 157-160.

- Szpilko, D. (2016), ‘NCRR – new foresight research method’, smart and efficient economy: preparation for the future innovative economy, Simberova, I., Milichovsky, F.,Zizlavsky, O. (eds), 21st International Scientific Conference on Smart and Efficient Economy – Preparation for the Future Innovative Economy, Brno University of Technology, Brno.

- Szymczak, M., Ryciuk, U., Leończuk, D., Piotrowicz, W., Witkowski, K., Nazarko, J. and Jakuszewicz, J. (2018), ‘Key factors for information integration in the supply chain – measurement, technology and information characteristics’, Journal of Business Economics and Management, 19 (5), 759-776.

- Tajfel, H. and Turner, J.C. (1986), ‘The social identity theory of intergroup behavior’, Psychology of intergroup relations, Austin, W.G. and Worhel, S. (ed), Nelson Hall, Chicago.

- Williams, K.Y. and O’Reilly, C.A. (1998), ‘Demography and diversity in organizations: a review of 40 years of research’, Research in Organizational Behavior, 20, 77-140.