Introduction

The importance of studying the employee communication between them is well documented (Jablin, 1979). These are situations where employees are satisfied with the communication between each other, do not complain about work, show loyalty, determination, and identify with the organization (Kramer, 1995). Many topics have been implemented so far regarding the issue of communication between employees. However, communication professionals deviate from basic concepts related to unexplored or not sufficiently researched topics (Daniels et al., 1997). These topics include certain traits, such as Machiavellianism, also communication traits, such as communication motives. Their relationship to employee satisfaction with their communication between employees has not been studied yet (Anderson, Martin, 1995). The fundamental principles of the theory of motives claim that people have specific needs, and that the fulfillment of these needs drives them to communicate; in other words, people’s motives for communicating influence their communicative choices and the way they communicate (Rubin, 1979, 1981). Motives for communicating are relatively stable features explaining why one chooses to communicate, which influences the way of communication. Motives affect people to communicate interpersonally to reach goals.

Theoretical basis

Living things communicate through sound, speech, body movements, and gestures in the best possible way to make others recognize their thoughts, feelings, problems, happiness, or any other information. Plants communicate through characters; animals communicate through sounds and movements to show the situation in which they find themselves. Human communication is different from others. Communication principles are based on a combination of old oral and written traditions. In organizations, marketers communicate with clients and employees, and with the public, they communicate through the exchange of information. The reason is to influence someone to behave in a certain way (Annan-Prah, 2015). According to Firdausi, Shaik and Tiwari (2020), communication is the basis of the existence and survival of people and organizations. It is a process that creates and shares thoughts, information, facts, views, and feelings among people to reach a common understanding. Employers in any business type implement effective communication that creates connections that build and strengthen relationships and increase productivity. In every industry, sector, or profession, communication includes handwritten words, e-mail, online messaging, online transactions, and social media, also nonverbal features such as body language, voice tone, and recognizing the appropriate way to interact in a variety of situations. According to Annan-Prah (2015), workplace communication is a process that involves a transfer and accurate replication of ideas secured by feedback to initiate actions to achieve organizational goals. In this communication, the sender is competent to send the idea; the recipient can accept or interpret that idea. This communication concerns the sharing of information between the business subject and its stakeholders, such as clients, employees, consumers, and suppliers, for the commercial benefit of the organization. This communication is carefully scheduled, organized, and expressed or compiled according to clear objectives.

A condition for a well-functioning company seems to be an utterly committed staff. Social intelligence plays an influential role in this context, and it also includes communication and empathy for employees. In today’s global work environment, stability, loyalty, and commitment are not enough to ensure the desired relationship between performance and positive work results (Frankovský, Zbihlejová, and Birknerová, 2015). Successful workplace communicators are open, approachable, supportive of others, adaptable, and emphasize what is necessary to accomplish in any situation. Employees at all levels of the organization need communication skills to understand formal and informal communication from their leaders, managers, and supervisors. Organizational culture, and the way people behave at work, are influenced by formal and informal interactions. Formal communication deals with information that passes through various channels, from management to employees and vice versa. It takes place in small groups at project teams, in working groups and in meetings, or in other small groups. Informal business communication takes place in any direction and can occur at all levels and areas of the organization. Consequently, successful communicators must choose the appropriate method or channel to send their message (Dwyer, 2019).

According to Perry and Miller (2018), the goal of communication is to bring a message to others clearly and unambiguously. It requires the efforts of the sender and recipient. It is a process that can be full of mistakes, and the recipient may misinterpret messages. It can cause immense confusion, unnecessary effort, and missed opportunities if not revealed. Communication is only successful if both, the sender, and the recipient, understand the information that results from the transmission. When it comes to communication skills, we also talk about the importance of withdrawing obstacles. Communication barriers can appear at every stage of the communication process (consisting of the sender, message, channel, recipient, feedback, and the context) and are the potential for misunderstanding and confusion. The aim should be to reduce the frequency of obstacles at each stage of the process with clear, concise, accurate, and well-planned communications and express our views without misunderstanding and confusion to be an effective communication means. Communication skills are significant in the workplace. The importance is visible in good and quality communication that avoids misunderstandings and conflicts. It creates productive work and performance that affects the company’s results. The importance of communication skills for effective organizational performance in the workplace cannot be overemphasized. Managers sometimes understand the importance of communication skills to increase the effectiveness of internal communication between management and employees. Insufficient communication is often the cause why employees leave work or look for other opportunities. Clear communication is a crucial part of optimizing employee and employer satisfaction. Therefore, it is not recommended to underestimate the importance of communication skills in all situations.

Various studies are working to improve communication skills. The research by Skrynnikova and Grigorieva (2019) deals with the peculiarities of improving written communication skills in the interactive environment of multinational companies. The authors examine the rhetorical and linguistic features, the language implementations, and strategies used by Russian business communicators when writing business letters in English and compare them with samples of business letters from native English speakers. Communication in the company with existing and potential partners, competitors, consumers, and the public is the basis of any effective activity of the company. In the context of a multinational company, communication in a multilingual environment becomes multipolar, where interpersonal professional communication and communication skills between employees are particularly significant for a company’s financial viability. According to the study, 11% of respondents lost the chance to run a successful business due to a lack of communication and language skills, and at least 50% of respondents thought they would need to acquire additional language and communication skills in the next period. According to the study, communication in English allows companies to integrate their branches and products into all regions of the world, compete successfully in global markets, and attract the best professionals. Incorrect or insufficient communication skills can result in intercultural conflicts and disruption of communication. Also, ignorance of the cultural characteristics of the host country presents many problems, although it does not affect all departments of society. The employee does not have to master cultural knowledge to the full but should have a clear idea of fundamental theories of culture.

According to Glossner (2019), the central identifications of Machiavellianism in psychology indicate that someone with the characteristics of Machiavellianism tends to exhibit many of the following tendencies: he focuses only on his ambitions and interests, prefers power to relationships, uses flattery, low level of empathy, avoids emotional attachment, rarely reveals his intentions, has trouble recognizing his own emotions. We often encounter manipulation in a work or school environment. For example, telling a coworker that we feel okay when depressed is a technical manipulation because it controls the partner’s understanding and response to us. Many people perceive manipulation negatively when it damages the physical, emotional, or mental health of a person who is being controlled.

A Machiavellian personality is manipulative and strategic. If there is a goal, the individual can very cleverly think about how to achieve it, regardless of the feelings of other people involved. Often these personalities use manipulative behavior to get what they want. They also use various scams and exploitation, often acting as non-emotional. Machiavellianism tends to be a more common source of trust for men, but it can affect anyone at any age. We can find the behavior of these personalities charming and engaging. They are trying to achieve their goals without becoming the center of attention. They are often cold-hearted, calculated, and cynical toward others and use people to their advantage (Frankovský, Birknerová, and Tomková, 2017a; Gokbayrak, 2021). The personality traits of marketers are essential. Various studies indicate that there is a need for a better understanding of employee involvement played by the personality in the organizational environment in the human resources sector. On the other hand, personality is considered a valid indicator of an individual’s performance and behavior. Machiavellians usually hold leadership positions within the organizational environment from which they manipulate and control others. They are less willing to follow the rules and procedures and focus on power over others. Machiavellians are usually sensitive to the social and organizational context, and if necessary, they can change tactics from cooperation to competition (Czibor and Bereczkei, 2012). Machiavellians can also spread rumors about their co-workers, hide important work information, or find sophisticated ways to denigrate their colleagues. However, despite their harmfulness, Machiavellians are characterized by manipulation flexibility strategies, from withdrawal to cooperation, depending on the context. Their goal is to gain personal benefits (Baron and Greenberg, 2003).

Methods

It is not easy to observe and measure unethical behavior in people. However, many are more willing to provide accurate information for anonymous research through paper and pen or a computer-controlled questionnaire than to conduct a face-to-face interview. The paper deals with research where communication skills and Machiavellianism of employees in the workplace in terms of selected socio-demographic data were determined. The research was carried out by a questionnaire focused on the analysis of communication skills of employees and the detection of Machiavellianism in employees within a selected sample of respondents.

The goal of the paper is to analyze the differences between the attributes of communication skills and Machiavellian expressions used by employees and their selected socio-demographic characteristics. There were specified mutual differences in residence, gender, marital status, and education of employees. Based on the goal, four hypotheses were formulated:

Hypothesis 1: There are statistically significant differences in the examination of selected attributes of communication skills and selected attributes of Machiavellian manifestations in employees in terms of residence.

Hypothesis 2: There are statistically significant gender differences in the examination of selected attributes of communication skills and selected attributes of Machiavellian manifestations in employees.

Hypothesis 3: There exist statistically significant differences in the examination of selected attributes of communication skills and selected attributes of Machiavellian manifestations in employees in terms of marital status.

Hypothesis 4: There are statistically significant differences in the examination of selected attributes of communication skills and selected attributes of Machiavellian manifestations in employees in terms of the highest level of education.

The first part of the questionnaire focused on fundamental demographic data. The second part of the questionnaire was focused on research, which was carried out in the form of two methodologies.

The first methodology, which focused on the employees’ communication skills, was a standardized Questionnaire of communication skills, compiled by Birkner and Birknerová (2015), adapted for the purposes of the topic. During the research, their methodology was used and analyzed respondents’ opinions on the assessment of their communication skills. The questionnaire contained 41 questions related to communication skills with a responding scale from 1 to 6 (1 – certainly no, 2 – no, 3 – rather than yes, 4 – rather yes than no, 5 – yes, 6 – certainly yes).

Factor analysis using the Principal Component Analysis method with Varimax rotation extracted four factors that characterize the attributes of communication skills. Together, these factors explain 54.064% of the variance. In terms of content, the factors were characterized as follows:

Empathy – respondents who have a high score in this attribute like to help others, perceive the emotions of others as if they were their own, try to empathize with the position of others, and can listen and understand other people. Reliability of items Cronbach’s Alpha – 0.703.

Feedback – high-scoring respondents require feedback from their colleagues, they think it is effective in communication, and they listen to the feedback but pay attention to its sincerity. Reliability of items Cronbach’s Alpha – 0.693.

Active listening – respondents with a high score in this attribute often nod when they listen to others, look them in the eye, let them speak because what others say is important to them, and have the ability to listen actively at a high level. Reliability of items Cronbach’s Alpha – 0.678.

Asking Questions – respondents with a high score in this attribute are familiar with questioning techniques because they consider it consequential, not leaving time for others to think about the answers, preferring open-ended questions. Reliability of items Cronbach’s Alpha – 0.593.

The second, CASEDI questionnaire, is a methodology compiled by Frankovský, Birknerová, and Tomková (2017b) to identify Machiavellian manifestations in business and managerial behavior. Three factors were extracted by factor analysis: calculation (CA), self-assertion (SE), and diplomacy (DI). The new CASEDI methodology contains statements that relate to the opinion of the respondent on manipulation between people. The individual items of the questionnaire were inspired by the publication The Prince by Nicollo Machiavelli (2007). A more detailed description of individual factors is stated in subchapter 5.5.1. The questionnaire contains 17 items, to which respondents answered using the scale: 0 – definitely no, 1 – no; 2 – rather than yes; 3 – yes rather than no; 4 – yes, 5 – definitely yes.

Factor analysis using the Principal Component method with Varimax rotation extracted three factors that confirmed the existence of the assumed factor structure of Machiavellian manifestations in business behavior. These factors were characterized as follows:

Caginess – respondents who have a high score in this factor believe that people’s control must be maintained at all costs. These respondents believe that it is necessary to tell others what they want to hear and to gain knowledge so that they can be used to control others. Cagey people are of the opinion that when two are competing, it is necessary to recognize whose victory is more beneficial, but in any case, it is beneficial to base their power on the control of other people. Cronbach’s alpha: 0.760.

Self-promotion – respondents who have a high score in this factor believe that only such a person is reliable, who relies on himself and his own strength. A successful person must always keep in mind that he must avoid allies stronger than himself. This factor also adheres to the view that whoever helps another to grab power, cuts the branch on which he sits. And then the one who wants to stay in power must consider all the necessary measures in advance and take them all at once so that he does not have to return to them later. Cronbach’s alpha: 0.521.

Diplomacy – respondents who have a high score in this factor are characterized by a constant collection of information, which can later be used for their own benefit. Skillful diplomacy is used to control others, and false and indirect communication is preferred. Respondents surround themselves with capable people and society in general and show them generosity and recognition at the right time. Cronbach’s alpha: 0.696.

The analyzed data were obtained by the online questionnaire method and snowball selection. As part of the implementation, 156 respondents were contacted, of which 58 (37%) were men and 98 (63%) were women. The average age of the respondents was 38,12 years, of which the youngest respondent was 20 years old, and the oldest respondent was 69 years old. According to residence, 79 (51%) employees were from the city and 77 (49%) employees were from the countryside. The distribution of respondents based on marital status was: 60 employees were single, and 96 employees were married. According to education, 112 (72%) employees had a secondary education, and 44 (28%) employees had a university degree.

Results

Hypothesis verification 1: We assume that there are statistically significant differences in the examination of selected attributes of communication skills and selected attributes of Machiavellian manifestations in employees in terms of residence.

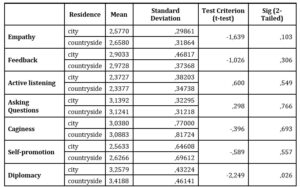

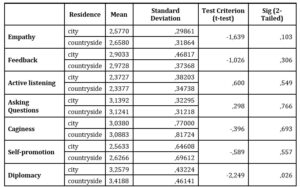

Selected attributes of communication skills and selected attributes of Machiavellian manifestations in employees in terms of residence are described in table 1.

Table 1: Verification of Hypothesis 1

(Source: Authors’ own processing)

T-test, the mathematical-statistical method, was used to compare the differences in selected attributes of communication skills and Machiavellian manifestations in employees from the city and the countryside. The attribute of Machiavellian manifestations: Diplomacy, was recorded with statistically significant differences in terms of residence of respondents. Higher average values were measured for employees living in the countryside. These rural workers, rather than urban workers, realize that they can only be successful if they adapt to changing conditions. Rural workers tend to use elements of skillful diplomacy. In other attributes, there was no recorded statistical significance in terms of residence.

Hypothesis 1 is confirmed because of the assumption that there are statistically significant differences in selected attributes of communication skills and Machiavellian manifestations in employees in terms of residence has been confirmed.

Hypothesis verification 2: We assume that there are statistically significant gender differences in the examination of selected attributes of communication skills and selected attributes of Machiavellian manifestations in employees.

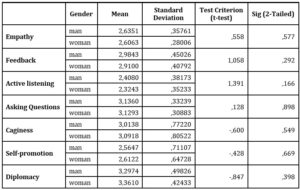

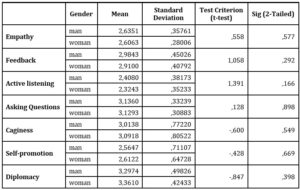

Selected attributes of communication skills and selected attributes of Machiavellian manifestations in employees in terms of gender are described in table 2.

Table 2: Verification of Hypothesis 2

(Source: Authors’ own processing)

T-test was used to compare the differences in men and women in selected attributes of communication skills and Machiavellian manifestations in terms of their employment. In terms of gender differences, there was no recorded statistical significance in any of the attributes of communication skills and Machiavellian manifestations.

Hypothesis 2 is unconfirmed because there was no recorded statistical significance in any of the attributes of communication skills and Machiavellian manifestations in terms of gender.

Hypothesis verification 3: We assume that there exist statistically significant differences in the examination of selected attributes of communication skills and selected attributes of Machiavellian manifestations in employees in terms of marital status.

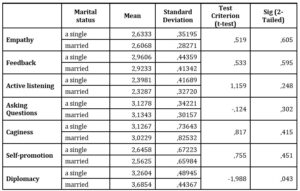

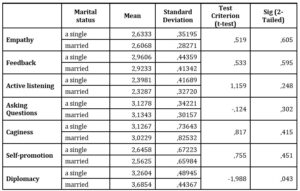

Selected attributes of communication skills and selected attributes of Machiavellian manifestations in employees in terms of marital status are described in table 3.

Table 3: Verification of hypothesis 3

(Source: Authors’ own processing)

T-test was used to compare the differences in selected attributes of communication skills and Machiavellian manifestations in married employees and single employees. The attribute of Machiavellian manifestations: Diplomacy, was recorded with statistically significant differences in terms of marital status of employees. Higher average values were measured in married employees. These employees surround themselves with capable people and constantly gather information to use it to their advantage. In other attributes, there was no recorded statistical significance in terms of marital status.

Hypothesis 3 is confirmed because the assumption that there exist statistically significant differences in selected attributes of communication skills and Machiavellian manifestations in employees in terms of marital status has been confirmed.

Hypothesis verification 4: We assume that there are statistically significant differences in the examination of selected attributes of communication skills and selected attributes of Machiavellian manifestations in employees in terms of the highest level of education.

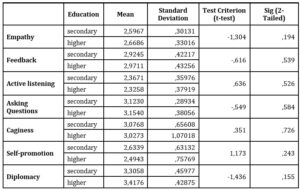

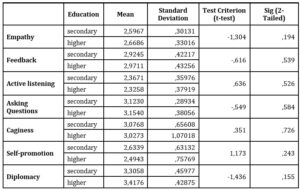

Selected attributes of communication skills and selected attributes of Machiavellian manifestations in employees in terms of the highest level of education are described in table 4.

Table 4: Differences in selected attributes of communication skills and Machiavellian manifestations in employees in terms of education

(Source: Authors’ own processing)

T-test was used to compare the differences in employees with secondary and the highest level of higher education in selected attributes of communication skills and Machiavellian manifestations. In terms of educational attainment of respondents, there was no recorded statistical significance in any of the attributes of communication skills and Machiavellian manifestations.

Hypothesis 4 is unconfirmed because there was no recorded statistical significance in any of the attributes of communication skills in terms of the highest level of education.

Discussion

In the context of communication skills and Machiavellian manifestations, the existence of statistically significant differences in selected attributes of the issue among employees who reside in the city, or the countryside, was examined. Higher average values in terms of Machiavellian manifestations were recorded for rural employees with the diplomacy attribute. It has been found that rural workers, rather than urban workers, realize more often that they can only be successful if they adapt to changing conditions. Rural workers tend to use elements of deft diplomacy.

Machiavellianism is founded completely on practicality, manipulation, exploitation, and deviousness, and is devoid of the traditional virtues of trust, honor, and decency. Words ethical and unethical are overlooked in the definition of Machiavellianism. Besides, Machiavellian-type behavior can be considered amoral (Fraedrich et al., 1989). High-Machs (people with high Machiavellianism) employ aggressive and devious methods to achieve goals without regard for the feelings, rights, and needs of others (Wilson et al., 1996). High-Machs manipulate more, win more, persuade others more (Schepers, 2003), have higher performance (Aziz et al., 2002), higher job strain, lower job satisfaction (Gemmill and Heisler, 1972), steal more, aggress more against an apologetic confederate (Harrell, 1980), and are more often rejected as social partners for most relationships (Wilson et al., 1996) in comparison to Low-Machs. These results could be compared to those of Bruner and Goodman (1947). Although their research concerns the economic background, it is also related to job satisfaction and manipulation. Research suggests that people from smaller or poorer economic backgrounds value money highly and overestimate its strength as their wealthy counterparts. In Singapore, employees with financial problems are obsessed with money.

By examining statistically significant differences in terms of gender in selected attributes of communication skills and Machiavellian manifestations in employees, we did not record any statistically significant difference in any of the selected attributes. Anderson and Martin (1995) reported that full-time workers communicated with superiors about needs associated with satisfaction, affection, and inclusion; and female workers expressed the needs associated with affection and relaxation. According to Lajčin, Sláviková, Frankovský, and Birknerová (2014), research on gender differences belongs to the fundamental research focus in the social sciences. The study of gender differences also plays a meaningful role in research aimed at manipulating employees. Research studies of gender differences in employees (Burke and Richardson, 2009; Aluko, 2009) focus more on the issue of stress in the work environment and the specifics of its operation in the context of gender differences. In many studies, the so-called work-family conflict arises more often for women due to the need to combine work and family demands.

Khelerová (2010) adds that an important area of communication skills is non-verbal communication, which dominates in women. It is non-verbal expressions that add emphasis and persuasiveness to pronounced words. Women can make contact with their partners and negotiate successfully through words as well as non-verbal signals. Unlike women, men focus mainly on the result. Women are not as competitive and aggressive as men. According to research by Christie and Geis (1970), men tend to score more in manipulation than women. But according to Rayburn and Rayburn (1996), manipulation scores are lower in men than in women. The results are different. Men are more concerned about career growth and are more likely to engage in unfair practices than the opposite gender (Malinowski and Berger, 1996). Women require kindness and special treatment as well as ethical thinking (Deshpande, 1997). Women like to converse because of good relationships and keep in touch, and men like to converse to find new information (Mikuláštík, 2006).

Since females tend to hold higher moral standards and are more ethical than males, it is apparent that females’ high scores on Machiavellianism may reflect their impression management tactics (Bolino and Turnley, 2003). Men have higher scores on the factor of Machiavellianism and corruption than women, as evidenced by research in the literature on Machiavellianism (Ross and Robertson, 2003). A statistically significant difference was recorded in the attribute of Diplomacy by examining statistically significant differences in selected attributes of communication skills and Machiavellian manifestations in employees in terms of marital status. Higher average values were documented in female and male employees who are married. These employees are capable people and constantly gather information to use it as an advantage. Unmarried people spend more time at work because they do not want to be lonely. Consequently, they have better relationships with other employees. The findings support Anderson and Martin’s (1995b) study that single employees communicate with other employees, including superiors, in a friendly and honest manner.

Čekan (2010) argues that communication is one of the central means of socialization at work. As Průcha (2002) states, socialization is determined by its social environment. The communication skills of individuals vary depending on their social affiliation. This success depends on the socio-cultural environment in which the individual lives and which language code he has acquired (Knausová, 2006). In connection with the issue of communication skills and Machiavellian manifestations, we also examined the presence of statistically significant differences in selected attributes of the researched issue among employees who have the highest secondary or higher education. However, within these differences, we did not document any statistically significant differences in any of the attributes of communication skills and Machiavellian manifestations.

Topol and Gable (1988) stated that those workers who had higher education and a high degree of Machiavellianism had low job satisfaction. We might expect that less-educated employees with a high degree of Machiavellianism may be less satisfied with their work. This relationship may have an impact on why employees with lower levels of education tend to communicate with employees with higher levels of education. The discussion, therefore, focuses on research into the motives of interpersonal communication. Machiavellianism can also be perceived as an interpersonal social competition aimed at achieving dominance (Barber, 1994). Ramanaiah et al. (1994) conducted research between Machiavellian orientation and human behavior. Individuals with a high Machiavellian score tended to manipulate more, persuading others in comparison with individuals with a low Machiavellian score. Highly scoring Machiavellians tended to be distrustful of others and could act unethically. Research suggests that Machiavellian orientation may predict unethical employee actions (Andersson and Bateman, 1997).

Conclusion

In the context of the analysis of manipulation in the work process, we examined statistically significant differences in selected attributes assessing the level of manipulation of leaders in terms of classification in the organization. Within an organizational environment, moral justification may be expressed by individuals who justify their immoral behavior by treating it as a means of salvation, such as other co-workers, from the exploitation of superiors. Research by Mafreia, Holman, and Elenescu (2021) suggests that high levels of Machiavellianism are significantly associated with the cognitive mechanisms that characterize these individuals as manipulative, cynical, secretive, suspicious, and empathy-free. According to Christie and Geis (1970), high Machiavellians differ significantly from low Machiavellians in the fact that high Machiavellians manipulate more, win more, and persuade less in situations where subjects interact face to face with others. The presented research results point to the differences that take place in the field of employment, mainly due to the classification of employees in individual job functions. Theoretical knowledge and research results represent possible views on the field of manipulation in the work process, where it is influential to know especially the definition of types of manipulators, reasons for manipulation, and the strategy of the manipulator. We consider the results of the studies to be a consequential starting point for future studies that will try to define and determine the most important predictors of the moral aspect in the organizational environment. A literature review suggests that high-scoring Machiavellians can manipulate and influence others in many situations and have an advantage over others in achieving their goals.

Acknowledgment

This paper is supported by the grant VEGA 2/0068/19 Attitudes towards Migrants in the Socio-psychological Context.

References

- Aluko, Y. A. (2009). Work-family Conflict and Coping Strategies Adopted by Women in Academia. Gender & Behaviour, 17(1), 2095 – 2122.

- Anderson, C. M., & Martin, M. M. (1995). Why employees speak to coworkers and bosses: Motives, gender, and organizational satisfaction. The Journal of Business Communication, 32, 265.

- Andersson, M. L., Bateman, T. S. (1997). Cynicism in the workplace: Some causes and effects. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 18, 449-469.

- Annan-Prah, E. C. (2015). Basic business and administrative communication. Xlibris Corporation. ISBN 978-1-5035-6882-2.

- Aziz, A., May, K., Crotts, J. C. (2002). Relations of Machiavellian Behavior with Sales Performance of Stockbrokers. Psychological Reports 90(2), 451–460.

- Barber, N. (1994). Machiavellianism and altruism: Effects of relatedness of target person on Machiavellianism and helping attitudes. Psychological Reports, 75, 403-422.

- Baron, A. R., Greenberg, J. (2003). Organizational Behaviour in Organization. Understanding and managing the human side of work. Canada: Prentice Hall.

- Birkner, M., Birknerová, Z. (2015). Communication skills in practice and their gender differences. Economic revue: A scientific journal of the Faculty of Business Administration of the University of Economics in Bratislava based in Kosice. 14(34), 28-40.

- Bruner, J.S., Goodman, C.C. (1947). Value and needs as organizing factors in perception. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 42, 33–44.

- Bolino, M. C., Turnley, W. H. (2003). More than One Way to Make an Impression: Exploring Profiles of Impression Management. Journal of Management 29, 141–160.

- Burke, R. J., Richardson, A. M. (2009). Work Experiences, Stress and Health among Managerial Women: Research and Practice.

- Christie, R., Geis, F. L. (1970). Studies in Machiavellianism. New York: Academic Press.

- Čekan, P. (2010). Reliability of human factors. New Trends in Aviation Development: proceedings of the 9th international scientific conference. Košice: TU, 35-38.

- Czibor, A., Bereczkei, T. (2012). Machiavellian people’s success results from monitoring their partners. Personality and Individual Differences, 53(3), 202–206.

- Daniels, T. D., Spiker, B. K., Papa, M. J. (1997). Perspectives on organizational communication (4th ed. Madison, WI: Brown & Benchmark.

- Deshpande, S. P. (1997). Manager’s Perception of Proper Ethical Conduct: The Effect of Sex, Age, and Level of Education, Journal of Business Ethics 16(1), 79–85.

- Dwyer, J. (2019). The business communication handbook. Australia: Cengage. ISBN 978-0-1704-1949-9.

- Firdausi, A., Shaik N., Tiwari, G. (2020). Communication [online]. Retrieved from: https://www.toppr.com/guides/business-studies/directing/communication/.

- Fraedrich, J., Ferrell, O. C., Pride W. (1989). An Empirical Examination of Three Machiavellian Concepts: Advertisers Vs. the General Public, Journal of Business Ethics 8(9), 687–694.

- Frankovský, M., Zbihlejová, L., Birknerová, Z. (2015). Links between the social intelligence attributes and forms of coping with demanding situations in managerial practice. In 2nd International Multidisciplinary Scientific Conference on Social Sciences and Arts. SGEM 2015, 1(1), 109–115.

- Frankovský, M., Birknerová, Z., Tomková A. (2017a). Analysis of Machiavellian manifestations in business behavior [online]. Retrieved from: http://opac.crzp.sk/?fn=docviewChild0001A679.

- Frankovský, M., Birknerová, Z., Tomková A. (2017b). Machiavellian Business Behavior Survey – VYSEDI (the handbook). Presov: Bookman.

- Gemmill, G. R., Heisler W. J. (1972). Machiavellianism as a Factor in Managerial Job Strain, Job Satisfaction, and Upward Mobility, Academy of Management Journal 15, 51–62.

- Glossner, V. (2019). Darkpsychology. Self Publisher. ISBN 978-8-8353-3535-1.

- Gokbayrak, N. S. (2021). All about machiavellianism [online]. Retrieved from: https://psychcentral.com/lib/machiavellianism-cognition-and-emotion-understanding-how-the-machiavellian-thinks-feels-and-thrives.

- Harrell, W. A. (1980). Retaliatory Aggression by High and Low Machiavellians against Remorseful and Non Remorseful Wrong doers, Social Behavior and Personality 8(2), 217–220.

- Jablin, F. M. (1979). Superior / subordinate communication: The state of the art. Psychological Bulletin, 86, 1201-1222.

- Khelerová, V. (2010). Communication and business skills of a manager. Prague: Grada Publishing.

- Knausová, I. 2006. Problems of language socialization. Verification of the validity of Bernstein’s theory of language socialization in the Czech environment. Olomouc: Votobia.

- Kramer, M. W. (1995). A longitudinal study of superior/ subordinate communication during job transfers. Human Communication Research, 22, 39-64.

- Lajčin, D., Sláviková, G., Frankovský, M., Birknerová, Z. (2014). Social intelligence as a significant predictor of managerial behavior. Journal of Economics, 62(6), 646-660.

- Mafrei, A., Holman, A. Elenescu, A. G. (2021). The Dark Web of Machiavellianism and Psychopathy: Moral Disengagement in IT organizations. Europe’s Journal of Psychology.

- Machiavelli, N. 2007. Vladař. [The Prince]. Prague: Nakladatelství XYZ s.r.o. ISBN 978-80-87021-73-6.

- Malinowski, C., Berger, K. A. (1996). Undergraduate Student Attitudes about Hypothetical Marketing Dilemmas, Journal of Business Ethics 15(5), 525–535.

- Mikuláštík, M. (2006). How to be a successful manager. Prague: Grada Publishing.

- Perry, L., Miller, T. (2018). Business Communication: Skills and Techniques. United Kingdom: ED-Tech Press. ISBN 978-1-83947-205-3.

- Průcha, J. (2002). Moderní pedagogika. Prague: Portál.

- Ramanaiah, V., Byravan N., A., Detwiler F. R. J. (1994). Revised Neo Personality Inventory Profiles of Machiavellian and NonMachiavellian People. Psychology Reports, 937-38.

- Rayburn, J. M. Rayburn L. G. (1996). Relationship between Machiavellianism and Type A Personality and Ethical-Orientation, Journal of Business Ethics 15, 1209–1219.

- Ross, W. T., Robertson, D. C. (2003). A Typology of Situational Factors: Impact on Salesperson DecisionMaking about Ethical Issues, Journal of Business Ethics 46(3), 213–234.

- Rubin, A. M. (1979). Television use by children and adolescents. Human Communication Research, 5, 109/ 120.

- Rubin, A. M. (1981). Uses, gratifications, and media effects research. In J. Bryant & D. Zillmann (Eds.), Perspectives on media effects. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 281-301.

- Schepers, D. H. (2003). Machiavellianism, Profit, and Dimensions of Ethical Judgment: A Study of Impact, Journal of Business Ethics 42, 339–352.

- Skrynnikova, I. V. Grigorieva, E. G. (2019). Enhancing for eignlanguage communication skills in international business environment. Bristol: IOP Publishing. ISSN 1757-8981.

- Topol, M. T., Gable, M. (1988). Job satisfaction and Machiavellian orientation among discount store executives. Psychological Reports, 62, 907-912.

- Wilson, D. S., D. Near Miller, R. R. (1996). Machiavellianism: A Synthesis of Evolutionary and Psychological Literatures, Psychological Bulletin 119, 285–299.