INTRODUCTION

Since the 1980s, research on family businesses has experienced significant growth in the academic field. Some researchers consider it to be in its adolescence phase (Gedajlovic and al., 2017), while others believe it has reached the “adulthood” stage (Jaskiewicz and al., 2020). Taking into account the involvement of a family in the management of the business, family firms tend to be a place where personal dreams are pursued and family goals are sought (Gersick and al., 1997). In contrast, the family business differs from its non-family counterpart by considering both economic and non-economic factors. It generally pursues family goals, which are considered socioemotional goals.

Indeed, family owners tend to dedicate their entire wealth to the service of the business, and when it comes to making strategic choices or decisions related to growth, for example, they take into consideration family goals that primarily aim to preserve their socioemotional wealth. Therefore, they seek to maintain family control and influence, promote the identification of family members with the business, build social ties, enhance emotional attachment among family members, and ultimately strengthen family ties through intergenerational succession (Gomez-Mejia and al., 2007; Berrone and al., 2012). Thus, in the context of a family business, setting goals is closely related to the concept of socioemotional wealth, which undeniably influences the family business’s internationalization.

In this paper, we aim to measure the relationship between socioemotional wealth (SEW) and the internationalization of family businesses. First, we will conduct a literature review analysis on SEW and internationalization. Then, we will present the research model and hypothesis. Finally, we will analyze the data, discuss the results, and conclude with the contributions, limitations, and future research avenues.

Theoretical Review

SEW

A paradigm potentially dominating the field of family business research in recent years, socioemotional wealth is considered to be the major key to understanding the behaviors of these

“phenomenon” companies, (Berrone and al, 2012). Indeed, this new approach dubbed “Homegrown theory” (Cruz and Arredondo, 2016) has enabled researchers to dig into previously difficult avenues of research and understand the reasons behind previously ambiguous family business choices. Theoretically rooted in the behavioral agency model, “The Socioemotional wealth (SEW)” is thought to predict family business owners’ risk-taking behaviors (Cruz and Arredondo, 2016). Gomez-Mejia and al (2007) referred to the non-economic benefits available to family business owners as socio-emotional wealth. According to the authors, the overriding objective for family members is to preserve this wealth. Thus, when making decisions, managers of a family firm will be guided by a concern for loss or gain in terms of socioemotional wealth. In other words, decisions will be evaluated in terms of their impact on socioemotional wealth. Obviously, decisions that will preserve this wealth will be given priority.

Despite the plurality of works and research on this concept, a universal definition remains absent (Martinez-Romero and Rojo-Ramirez, 2016). This is probably due to its youth. However, its definition is currently at the center of academic debate. While the majority of researchers support the definition proposed by Gomez-Mejia and al, (2007), others consider that the concept remains ambiguous and has blurred boundaries (Miller and Le Breton-Miller, 2014). Nevertheless, all researchers agree on the importance of socio-emotional wealth as the dominant paradigm “in Family Business Research” (Cruz and Arredondo, 2016).

Returning to the first research about SEW, Gomez-Mejia and al (2007) refer to the non-financial aspects of the family business to define socio-emotional wealth, namely, the sense of belonging, emotional attachment, identification with the family business, decision-making imbued with family values, preservation of the family dynasty, conservation of social capital, recruitment based on blood ties rather than skills and finally family altruism. Thus, everything that distinguishes a family business from a non-family business seems to be a dimension of socioemotional wealth.

For their part, Berrone and al (2012) consider that socio-emotional wealth corresponds to a stock of emotional value. They state: “The stock of affect-related value that a family derives from its controlling position in a particular firm”. Similarly, Cruz and al (2012) define socio-emotional wealth from an affective and emotional perspective. Indeed, the authors refer to it as Affective endowment. It represents an affective and emotional endowment likely to influence the performance of the family business. According to Chrisman and al (2007), family business members obtain both financial and non-financial benefits. This non-financial value corresponds to socio-emotional wealth. It can take different forms, depending on the family’s vision of the business and the degree to which this non-financial value contributes to the well-being of family members (Chua and al, 1999). Thus, socio-emotional wealth represents a panoply of nonfinancial advantages and benefits that enable family members to satisfy their affective and emotional needs through their involvement in the company’s management. Finally, it is the importance that owners attach to these non-financial benefits that will determine the choices and objectives of the family business.

Ultimately, family members take advantage of the business to satisfy their social and emotional preferences (Daily and Dollinger, 1992). Thus, family members seek to maximize not financial returns, but rather socio-affective endowment, including esteem, prestige, pride, recognition, affection, identity, self-actualization…etc. Indeed, Gomez-Mejia and al (2010) argue that family business owners are expected to create and preserve socio-emotional wealth at the expense of financial interests. Consequently, their strategic decisions will be guided by an aversion to the risk of losing their socio-emotional advantages. However, some family businesses may have short-term socio-emotional goals such as securing employment for members of the family community, while others set long-term socio-emotional goals such as preparing a succession plan (Chrisman and Patel, 2012).

By way of conclusion, we can define SEW as an emotional value and socio-affective endowment inherent to family businesses, from which all family members benefit, whether they are active or inactive in the business. It reflects the psychological, sociological and emotional dimensions of the family business. Family business owners seek to preserve their socioemotional wealth. Losing this socio-emotional richness implies a loss of intimacy and an inability to meet the expectations of the family community. The following table summarizes the main definitions of socio-emotional wealth.

Table 1 – SEW: Main Definitions

Source: LARIOUI, 2020

Source: LARIOUI, 2020

Internationalization of Family Business

“Internationalization… an active, conscious phenomenon, organized over time with varying degrees of involuntariness and willingness” (Julien and St-Pierre, 2009). Internationalization is a multi-dimensional variable. In this paragraph, different aspects of the internationalization process will be addressed. Firstly, the concept of internationalization will be presented, and the various reasons that motivate companies to venture into international markets will be discussed. Subsequently, the different dimensions of internationalization and the entry modes adopted by companies will be presented.

Internationalization is an interesting concept as it “affects the objectives, culture, structure, and strategy of the firm,” which sometimes hinders their internationalization (Okoroafo and Koh, 2009). Indeed, the nature and characteristics of family firms are particularly tested by their internationalization process (Claver, 2009). Therefore, formulating and implementing an internationalization strategy for family firms is more challenging.

Furthermore, several existing studies affirm that the unique characteristics of family firms influence their international dimension. However, there is no consensus on which of these characteristics facilitate or limit internationalization (Arregle, Hitt, and Mari, 2019).

For example, in a study on the international orientation of major family firms worldwide, (C. Carr and S. Bateman, 2010) concluded that family firms are more internationally oriented than non-family firms, while (Gomez-Mejia, Makri, and Kintana, 2010) arrived at the opposite conclusion. Moreover, stewardship theorists (Davis, Schoorman, and Donaldson, 1997) suggest that the strong identification of family owner-managers with the firm and their commitment to the long-term well-being of the firm and its employees motivate them to act in the best interest of the firm, even in the face of challenges and risks. The stewardship theory thus contributes to explaining the positive influence of family ownership and management on the international scale of a family firm (Deeksha and Gaur, 2013); (Zahra, 2003).

Several studies have examined family firms and addressed the question of their internationalization. (Gomez-Mejia, Haynes, Núñez-Nickel, Jacobson, and Moyano-Fuentes, 2007); (Gomez-Mejia, Makri, and Kintana, 2010), and others (e.g., (F. Chirico, R. Gomez-Mejia, K. Hellerstedt, C. Withers, and M. Nordqvist, 2019)) provide evidence suggesting that family executives are so averse to the loss or reduction of the RSEM (Resource-Based View) that they are willing to give up a portion of the profit to preserve it. However, the effects of this loss aversion on the internationalization of family firms are not clear. (Gomez-Mejia, Makri, and Kintana, 2010) note that “family firms are pulled in two opposite directions.”

The literature suggests that a more nuanced approach to questions regarding the influence of specific attributes on the extent of internationalization of family firms could help resolve some of these contradictions. For example, internationalization requires significant managerial resources (Hitt, L. Bierman, K. Uhlenbruck, and K. Shimizu, 2006), which are often lacking in family firms due to their strong reliance on family leadership and compensation practices (Neckebrouck, Schulze, and Zellweger, 2018).

Conceptual Model and Research Hypotheses

Socio-emotional wealth is one of the key dimensions that explains the heterogeneous nature of family businesses as it encompasses multiple objectives. The dimensions of socio-emotional wealth in family businesses can be differently related to the decision of internationalization in family businesses (Berrone, Cruz, and Mejia, 2012). Indeed, family business owners make decisions with their socio-emotional wealth as a reference point and are primarily averse to losses when it comes to protecting and maintaining this wealth.

The presence of the family greatly influences strategic decision-making. When a family business opts for internationalization, it generally chooses the least risky entry modes, such as exports and imports, to avoid the loss of identity and cultural conflicts. Thus, it prefers to preserve its socio-emotional wealth rather than embark on the internationalization process, and the family operates on a purely emotional register, leading to underperformance of family businesses.

In this subsection, we will detail the relationship between the dimensions of socio-emotional wealth and internationalization.

Identification with the Firm and Internationalization

Research on family businesses has shown that the intertwining of family and business gives rise to an intrinsically unique identity within family businesses (Berrone, Cruz, and Mejia, 2012). The identity of the owner of the family business is linked to the management of the organization, which usually bears the family name (Berrone, Cruz, and Mejia, 2012). This dimension implies that the owning family cares about the human and social relationships maintained with customers, partners, and the entire community. In particular, family businesses seem to be highly concerned about their employees and professionals who are sometimes seen as part of the family sphere. Some studies have shown that the importance of family ownership reduces the likelihood of mass layoffs (Block, 2010), suggesting that family owners care more about their reputation than others, as they are expected to fulfill their social responsibilities. More generally, the business is perceived both by internal and external stakeholders as an extension of the family itself (Berrone, Cruz, and Mejia, 2012).

This socio-emotional objective can have a significant influence on internationalization. On the one hand, it could be expected that the family is encouraged to grow and internationalize the business, which is considered by the owners as an extension of themselves, for example, through the branding of their eponymous products.

H1: Therefore, it can be said that the identity of family business owners leads them to choose full control of the subsidiary instead of shared control so that they can develop their international reputation.

Emotional Attachment and Internationalization

Emotions and emotional involvement are distinctive traits of family businesses, where both the family and business systems must coexist despite their apparent antagonism (Hirigoyen and Basly, 2019). Naturally, emotions and feelings can be positive or negative, leading to different outcomes depending on the context in which they are experienced or expressed. Research has highlighted the impact of certain emotions on the management, governance, and strategy of family businesses (Zahra, 2003; Davis and Harveston, 2016; Poza and Messer, 2001; Rau, 2013). Emotions may be even more significant than economic and financial goals, as some studies have shown that strategic decisions in family businesses can be solely motivated by family considerations reflecting the owners’ commitment to the well-being and/or emotions of family members (Poza and Messer, 2001; Kahn and Henderson, 1992).

While family members can be altruistic (Schulze and William, Toward a Theory of Altruism in Family Firms, 2003) or trustworthy (Cruz, Justo, and De Castro, 2012), they can also exhibit or experience selfishness, opportunism, and narcissism (Ranft and O’Neill, 2001). Additionally, family members may be emotionally attached to their business as they feel psychologically owners (Pierce and Sarason, 1991) and perceive the business as an extension of themselves (Basly, 2019). Conversely, if the emotional costs outweigh the emotional benefits derived from the business, their commitment to the business may weaken, and they may be tempted to sell the business (Rau, 2013). Pursuing this specific goal has a significant impact on internationalization.

Firstly, certain positive emotions such as the owner’s altruism may be favorable to the internationalization of their personal copy, as it helps manage conflicts and mitigate perceived risks (Zahra, 2003). For example, Cadiou, Cadiou, and N’Goma (2017) emphasized the role of trust relationships between the founder and the next generation, primarily based on the latter’s skills (competence-based trust), in determining the climate for managing and resolving conflicts related to significant internationalization decisions. However, internationalization is a strategic choice that can trigger conflicts among family members (Zahra, 2003). In particular, conflicts among shareholders can paralyze the internationalization process, ranging from identifying internationalization opportunities to choices regarding how to exploit these opportunities, thereby inhibiting internationalization (Sciascia, 2012). Generally, the common divergence that may exist between financial and non-financial goals or between business goals and family goals could lead to conflicts regarding the necessity of internationalizing the business (Zahra, 2003). Disagreements among family members can also arise regarding the timing, scope, pace of internationalization, or entry modes to adopt (Zahra, 2003). In short, internationalization can be a decision that challenges the harmony, unity, and emotional well-being of the family. Overall, emotional attachment to the business seems more likely to play a detrimental role in the internationalization of the business as family members may fear the loss of family influence (e.g., if the business is forced to hire external managers or establish cross-border partnerships) and the reduction of the family character of the business, leading the business to maintain complete control over subsidiaries established internationally.

H2: The emotional attachment of family members positively influences complete subsidiary control.

Family Bonds Sustainability through Success

The maintenance of the business for future generations is generally considered as a key objective for family businesses (Kets de Vries M. F., 1993; Zellweger, Kellermanns, Chrisman, and Chua, 2012; Sami and Paul-Laurent, 2019). Many family businesses have longer-term planning horizons (Miller & Breton-Miller, 2006). Preserving the family dynasty, perpetuating family values through the business, and the desire to pass on the business to the next generation promote a “generational investment strategy creating patient capital,” which involves a commitment to strengthening capabilities and the learning of the next generation (Sirmon and Hitt, 2003; Berrone, Cruz, and Mejia, 2012). Consequently, Zellweger, Kellermanns, Chrisman, and Chua (2012) note that the perceived socio-emotional value increases with the duration of the association and the desire for transgenerational longevity, a distinctive characteristic of family businesses. Specifically, according to these authors, the desire of family business owners to possess a sustainable business across family generations affects the price at which the owner is willing to sell the family business. Indeed, the family business seeks to make decisions that will ensure the family dynasty. Thus, family owners often seek to exercise complete control over the decisions made during internationalization to approve those that favor the family dynasty.

H3: Therefore, the sustainability of family bonds through succession drives business owners to choose complete subsidiary control.

We summarize the research hypotheses in the following conceptual model:

FIG. 1: CONCEPTUAL MODEL

In our research, we assume that a family business that opts for internationalization has competent management teams, as a competent management team is capable of quickly identifying business opportunities, planning, and implementing international marketing. Additionally, a competent management team enables the accumulation of knowledge and experience, which increases the chances of successful internationalization.

Similarly, the model assumes that when a family business chooses subsidiary formation in a foreign country, it prefers creating a subsidiary over acquisition. Through this choice, the family business can preserve control over operations abroad and maintain its identity. This choice is also motivated by the need for a gradual commitment of resources (investment spread) and the opportunity to develop market experience through independent means.

Lastly, the model considers that when a family business opts for subsidiary formation in a foreign country, it chooses full control over shared control because it wishes to maintain control over the subsidiary (control preservation) and avoid the loss of identity and cultural conflicts.

Research Methodology

In order to measure SEW, we utilized the REI scale, previously validated by Hauck and al. (2016). As for internationalization, we employed measurement scales that have been empirically tested and validated by several researchers (Arregle and al., 2021) (Basly, 2005) (Basly, 2019).

The research model was tested on a sample of 51 Moroccan family businesses collected through a survey administered to top executives. We chose the family leader as the respondent for our survey because they are more involved in strategic decisions, such as international expansion, on one hand, and they have insights into the objectives and vision of the owning family, on the other hand. Additionally, they possess more information about the intensity of relationships among family members, between family members and non-family employees, and even between the family business and its stakeholders. The collected data were analyzed using SPSS software. Finally, the hypotheses were tested using the partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) method.

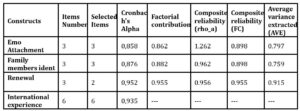

Table 2- Validity and Reliability of Constructs

Source: own’s elaboration

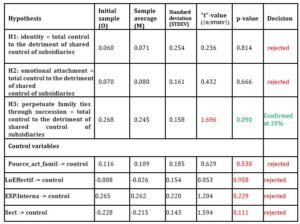

This test represents the structural relationships between constructs and allows for measuring the hypothesized links between independent variables and the dependent variable. Its purpose is to determine the strength of the hypotheses by calculating the probability of error (P value =<5%). Additionally, it should be noted that a hypothesis will be confirmed only if the student’s t-value is greater than or equal to 1.96. To perform this test, we will use the Bootstrapping technique in SmartPLS 4.

Table 3– Path Coefficient

Source: SmartPLS outputs

Source: SmartPLS outputs

In addition, the results provided by PLS (Partial Least Squares) show that our model is significant, as the R² value is greater than 0.1 and equal to 0.213. Furthermore, the Goodness of Fit (GOF) index is above 0.36 and equal to 0.41. Thus, we can conclude that the quality of fit of our model is very satisfactory. Upon examining the results provided by SmartPLS and summarized in the table above (Table 3), it is revealed that none of the hypotheses can be confirmed, as even Hypothesis 6: The more the owning family seeks to perpetuate family ties through succession, the more the family business tends to prefer full control over shared control of subsidiaries in the context of internationalization, which is significant at the 10% threshold, has a student’s “t” value less than 1.96.

Furthermore, the assumed positive impacts of the other variables (H4, H5) on full control of subsidiaries in the context of internationalization have high error probabilities exceeding the minimum threshold of 5%, specifically 81.4% for Hypothesis 4 and 66% for Hypothesis 5. The student’s “t” values for the rejected hypotheses are below 1.96. This led us to reject them based on statistical norms. This implies that the collected observations do not provide sufficient evidence to reject the null hypothesis (H0), which states that there is no correlation between the independent variable and the dependent variable. Regarding the control variables (family ownership, size, international experience, and industry sector), the SmartPLS outputs reveal that none of these variables have a significant effect on subsidiary control. The SmartPLS 4.0 software provides the structural model diagram of our research, as presented below:

FIG. 2: STRUCTURAL MODEL

Source: Smart PLS outputs

Discussion

The purpose of our research was to verify the relationship between the dimensions of socioemotional wealth accumulated by owners of Moroccan family businesses and internationalization through subsidiaries. This relationship was modeled using three independent variables (identity, emotional attachment, and perpetuity) and one dependent variable (total control vs. shared control) within the context of surveyed Moroccan family businesses.

The results from this test of the structural model reveal that only the independent variable “perpetuity” has a positive impact on total subsidiary control. On the other hand, the hypotheses examining the impact relationship between emotional attachment and identification as independent variables have no impact on the total control variable. These results further enrich the conclusions and suggest new avenues for research.

Indeed, the objective of perpetuating family ties through succession seems to have a positive impact on total subsidiary control. Several researchers consider the intention for intergenerational continuity as a criterion for defining a family firm (Ward, 1987; Sharma, 1997; Fayolle, 2009; Basco, 2017).

Previous research on the perpetuity variable in the context of family businesses has shown the importance of this dimension in preserving the values of the company by maintaining family ties between successor generations (Kets de Vries, 1993; Zellweger, 2012; Basly, 2019). Ensuring generational continuity is considered a key objective for family businesses, as they tend to prefer a family member as a successor in the entrepreneurial process, involving the transfer of power, leadership, knowledge, and ownership, even if non-family profiles prove to be more competent. This can be explained by the owners’ desire to preserve the family dynasty (Gomez-Mejia, 2011), which goes hand in hand with the desire to maintain total control over the business.

The outputs from the analyses conducted using SmartPLS allow us to confirm, in the Moroccan context, our initial hypothesis stating the existence of a positive link between the perpetuation of family ties through succession and total subsidiary control, supporting the theoretical postulates put forth by the authors.

The result of the test on the hypothesis of family member identification’s impact on total subsidiary control of the surveyed Moroccan businesses reveals that family member identification has no impact on total subsidiary control. This result challenges the theoretical claims that support a significant relationship between family member identification and total subsidiary control (Berrone, Cruz, and Gomez-Mejia, 2012; Block, 2010). However, our results align with the statements made by authors such as Zahra (2003) and Zellweger (2013). Considering these results, we can reject our theoretical hypothesis.

Finally, for the hypothesis testing the relationship between emotional attachment as an independent variable and total control as a dependent variable, our results show the absence of a significant relationship between these two variables. These findings are supported by the statistical results from SmartPLS. Thus, we can confirm that in Morocco, emotional attachment does not influence subsidiary control.

Contributions, Limitations & Research Perspectives

Research Contributions

The first contribution lies in the field of research. Our work is part of a recent research domain in Morocco and addresses a current topic at the heart of the Moroccan economy, namely family businesses. It contributes to explaining the dimensions of socio-emotional wealth that promote or hinder total control at the expense of shared control in the context of the internationalization of family businesses in the Moroccan context, while attempting to complement previous theoretical and empirical work on the internationalization of family businesses. Our contribution lies in the mobilization of a rich theoretical framework consisting of agency theory, behavioral agency theory, resource-based theory, network theory, and various enrichments derived from the socio-emotional wealth paradigm. This diversity is due to the complexity of the subject and its multidimensional nature. The combined theoretical framework we have utilized provides a comprehensive and multidimensional explanation of the impact of socioemotional wealth on the internationalization of family businesses in Morocco. Our research also differentiates itself by the complementary use of two software programs: SPSS software for scale purification and Smart PLS 4.0 software for validating the measurement model and testing structural relationships.

Lastly, from a managerial perspective, our research contributes to explaining the specificities of Moroccan family businesses and their internationalization. These businesses are concerned with preserving their socio-emotional wealth at the expense of decision-making. In this sense, we recommend that Moroccan family businesses ensure that decision-making is not detrimental to the interests of the company and all stakeholders.

Research Limitations

Far from being perfect, this work has attempted to highlight certain aspects of socio-emotional wealth and the internationalization of Moroccan family businesses. The obtained results and research contributions are subject to a number of limitations. The first limitation is related to the size of our sample. Faced with the difficulty of finding a reliable database of Moroccan family businesses with international subsidiaries, we had to identify them ourselves: contacting data providers, visiting companies, contacting professional associations, using the ASMEX directory, OMPIC, contacting the CGEM and the Exchange Office. This resulted in a limited sample size. This restriction can only limit the generalization of the results obtained to the entire population of family businesses with international subsidiaries.

Similarly, the results would have been more significant if they had been compared to the behavior of family businesses operating in contexts relatively similar to the Moroccan context. Conducting research in this direction, however, requires significant financial resources and a very high time budget. Additionally, we limited ourselves solely to subsidiary formation as the ultimate strategy for internationalization. However, there are other strategies, such as exporting, offshoring, outsourcing, etc. Certainly, these limitations can be beneficial for triggering further research, which is indeed necessary to complete the process of understanding the relationship between socio-emotional wealth and the internationalization of family businesses. The non-inclusion of other variables influencing socio-emotional wealth at the international level is also theoretically questionable. Other internal variables specific to family businesses can shed better light on the issue, such as generation, age of the business, among others. Incorporating these variables may be relevant in future research since the intensity of socio-emotional goals, namely identity, emotional attachment, and the longevity of the family business, can vary depending on these contextual data. As family businesses are still led by their founders, older companies have a higher likelihood of developing high socio-emotional wealth.

Perspectives and Future Research Directions

The first research direction involves introducing the temporal dimension into the analysis, a dimension often overlooked in previous studies on the internationalization of family businesses. Indeed, various studies related to the internationalization of family businesses have relied on synchronic methodological approaches, analyzing a sample of companies at a specific point in time. However, in our view, internationalization is inherently dynamic and characterized by a strong temporal aspect. Therefore, it would be interesting to adopt a diachronic approach (longitudinal study) to better understand the strategies and, most importantly, the process of internationalization of family businesses.

References

- Angué. (2018). Réseaux et processus d’internationalisation dans le secteur des sciences du vivant. Management international / International.

- Arregle, J. L., Chirico, F., Kano, L., & Schulze, W. S. (2021). Family firm internationalization: Past research and an agenda for the future. Journal of International Business Studies.

- (2017). “Where Do you Want to Take Your Family Firm?” A Theoretical and Empirical Exploratory Study of Family Business Goals.

- (2005). L’internationalisation de la PME familiale : Une analyse fondée sur l’apprentissage organisationnel et le développement de la connaissance. Thèse de Doctorat.

- (2019). Familiness, socio-emotional goals and the internationalization of French family SMEs.

- Berrone, P., Cruz, C., & -Mejia, L. R. (2012). Socioemotional Wealth in Family Firms: Theoretical Dimensions, Assessment Approaches, and Agenda for Future Research. Family Business Review, 25(3), 258-279.

- Block, J. (2010). Family management, family ownership and downsizing: evidence from S&P. Family Business Review, 1-22.

- Boellis, A., Mariotti, S., Minichilli, A., & Piscitello. (2016). Family involvement and firms establishment mode choice in foreign. Central Archive at the University of Reading.

- Cadiou, C., Cadiou, K., & N’Goma, F. (2017). Performance and Defense of the Family Unit: The Value of Emotional Capital. International Management, 22(1), 87–99.

- Carr, C., & Bateman, S. (2009). International strategy con-figurations of the world’s top family firms. ManagementInternational Review, 733-758.

- Charreire, S., & Huault, I. (2003). Cohérence épistémologique et recherche en management. Xième Conférence de l’Association Internationale de Management Stratégique.

- Chen, H.-L. (2011). Internationalization in Taiwanese family firms. Global Journal of Business Research, 15-23.

- (2010). Modèle d’Uppsala et implantation des firmes multinationales agroalimentaires. Revue française de gestion.

- (2010). How to Write Up and Report PLS Analyses.

- Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach for structural equation modeling. Modern methods for business research.

- Claver, E. R. (2009). Family firms’international commitment: The influence of family-related factors. Family Business Review, 125-135.

- (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (2nd ed.).

- Cox, D., & Snell, E. (1989). Analysis of Binary Data. 2nd Edition, Chapman and Hall/CRC, London.

- Cruz, ; Justo, ; De Castro, . (2012). Does family employment enhance MSEs performance? Integrating socioemotional wealth and family embeddedness perspectives. Journal of Business Venturing, 27, 62-76.

- Davis, P. S., & Harveston, P. D. (2016). Internationalization and Organizational Growth: The Impact of Internet Usage and Technology Involvement Among Entrepreneur-led Family Businesses. Family Business Review.

- (1997). Market. Etudes et Recherches en Marketing. Nathan.

- Chirico, R.Gomez-Mejia, L., K.Hellerstedt, C.Withers, M., & M.Nordqvist. (2019). To Merge, Sell or Liquidate? Socioemotional Wealth, Family Control, and the Choice of Business Exit. Journal of Management, Forthcoming.

- (2009). L’entrepreneuriat familial, un champ en devenir.

- Fernández, & Nieto, M. (2006). Impact of ownership on the international involvement of SMEs. Int. Business Stud., 340-351.

- Gomez-Mejia. (2011). The Bind that Ties: Socioemotional Wealth Preservation in Family Firms.

- Gomez-Mejia, Haynes, .Núñez-Nickel, Jacobson, & Moyano-Fuentes. (2007). Socioemotional wealth and business risks in family-controlled firms: Evidence from Spanish olive oil mills. Management and Entrepreneurship.

- Gomez-Mejia, L. R., Makri, M., & Kintana, M. L. (2010). Diversification Decisions in Family-Controlled Firms. Journal of Management studies, 47(2), 223-252.

- Gómez-Mejía, R., L., Haynes, K. T., Núñez-Nickel, M., Jacobson, K. J., & Moyano-Fuentes, J. (2007). Socioemotional Wealth and Business Risks in Family-controlled Firms: Evidence from Spanish Olive Oil Mills. Administrative Science Quarterly, 52(1), 106-137.

- Habbershon, T. G., & Williams, M. L. (1999). A Resource-Based Framework for Assessing the Strategic Advantages of Family Firms. Family Business Review, 12(1), 1-25.

- (2017). Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling.

- Hauck, J., Suess-Reyes, J., Beck, S., Prügl, R., & Frank, H. (2016). Measuring socioemotional wealth in familyowned and -managed firms: A validation and short form of the FIBER Scale. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 7(3), 133-148.

- Hirigoyen, s., & Basly, s. (2019). The 2008 financial and economic crisis and the family business sale intention: A study of a French SMEs sample. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 571-594.

- Hitt, M. A., L.Bierman, K.Uhlenbruck, & K.Shimizu. (2006). The importance of resources in the internationalization of professional service firms: The good, the bad, and the ugly. Academy of Management Journal.

- Hosmer, D., & Lemeshow, S. (1989). Applied Logistic Regression. john Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York.

- STEINEROWSKA-STREB. (2021). INTERNATIONALIZATION OF POLISH ENTERPRISES. S I L E S I A N U N I V E R S I T Y O F T E C H N O L O G Y P U B L I S H I N G H O U S E.

- Kahn, J. A., & Henderson, D. A. (1992, Septembre 1). Location Preferences of Family Firms: Strategic Decision Making or “Home Sweet Home” ? Family Business Review.

- Kellermanns, F. W., & Eddleston, K. A. (2007). Family Perspective on when Conflict Benefits Family Firm Performance. Journal of Business Research.

- Kets de Vries. (1993). The dynamics of family controlled firms : The good and the bad news.

- Kets de Vries, M. F. (1993). he dynamics of family controlled firms: The good and the bad news. Organizational Dynamics, 59–72.

- Kontinen, T., & Ojala, A. (2012). Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 39-55.

- Kontinen, T., & Ojala, A. (s.d.). Internationalization Pathways of Family SMEs: Psychic Distance as a Focal Point. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development.

- Kraus, S., Harms, R., & Fink, M. (2010). Entrepreneurial marketing: moving beyond marketing in new ventures. International Journal Of Entrepreneurship And Innivation Management.

- Larioui, L. (2020). Les objectifs socio-émotionnels des PME familiales : Impact sur l’efficacité du conseil d’administration ou de gérance. Hassan 2nd University. Morocco.

- Larioui, L. (2020). Board Effectiveness in Small and Medium-Sized Family Businesses: A Socioemotional Wealth Approach. Academic Conference Family Business in the Arab World “Family Business in emerging, developing, and transitional economies”. American University of Sharjah. 4 – 5 Nov. Shrajah. UAE.

- Laufs & Schwens, C. (2014). Foreign market entry mode choice of small and medium-sized enterprises: A systematic review and future research agenda. International Business Review, 1109-1126.

- Lawrence, W., & Luostarinen. (1988). Internationalization: Evolution of a Concept. Journal of General Management, 155-171.

- Liu, X., Xua, W., Pan, Y., & Duc, E. (2015). may have underestimated dissolved organic nitrogen (N) but overestimated total particulate N in wet deposition in China. Science of The Total Environment, 300-301.

- Martínez-Romero, M., & Rojo-Ramírez, A. (2016). SEW: Looking for a definition and controversial issues. European Journal of Family Business, 6(1).

- (1992). A Primer for Soft Modeling.

- Miller, D., & Breton-Miller, I. L. (2006). Family Governance and Firm Performance: Agency, Stewardship, and Capabilities. Family Business Review, 73 -87.

- Neckebrouck, J., Schulze, W., & Zellweger, T. (2018). Are family firms good employers ? American Psychological Association.

- Pierce, G., Sarason, I., & Sarason, B. (1991). General and relationship-based perceptions of social support : are two constructs better than one ? . Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

- Poza, E. J., & Messer, T. (2001). Spousal Leadership and Continuity in the Family Firm. Family Business Review, 25-36.

- Rammal, H. G., Cavusgil, T. S., Knight, G., & Rose, E. (2014). International Business: The New Realities.

- Ranft, A., & O’Neill, H. (2001). Board Composition and High-flying Founders : Hints of Trouble to Come ?

- Rau, S. B. (2013). Emotions Preventing Survival of Family Firms: Comments on Exploring the Emotional Nexus in Cogent Family Business Archetypes: Towards a Predominant Business Model Inclusive of the Emotional Dimension. Entrepreneurship Research Journal, 425-432.

- Sami, B., & Paul-Laurent, S. (2019). Familiness, socio-emotional goals and the internationalization of French family SMEs. Journal of International Entrepreneurshi.

- Schulze, & William. (2003). Toward a Theory of Altruism in Family Firms. Journal of Business Venturing.

- Sciascia, S. (2012). The role of family ownership in international entrepreneurship: exploring nonlinear effects. Small Business Economics.

- (1997). Determinants of Initial Satisfaction with the Succession Process in Family Firms: A Conceptual Model.

- Simon, H. (1996). Hidden Champions: Lessons from 500 of the World’s Best Unknown. Harvard Business School Press .

- Sirmon, D. G., & Hitt, M. A. (2003). Managing Resources: Linking Unique Resources, Management, and Wealth Creation in Family Firms. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 27(4), 339-358.

- (2004). A global goodness-of-fit index for PLS structural equation modelling.

- Wang, & al. (2010). Potential and flux landscapes quantify the stability and robustness of budding yeast cell cycle network. roc Natl Acad Sci USA.

- (1987). Keeping the Family Business Healthy: How to Plan for Continuous Growth, Profitability, and Family Leadership.

- (2009). Using PLS Path Modeling for Assessing Hierarchical Construct Models: Guidelines and Empirical Illustration.

- Wubben ; Boerstra ; Dijkman. (2012). Internationalisatie: groeien over grenzen.

- (2003). International expansion of U.S. manufacturing family. Journal of Business Venturing, 495 – 512.

- (2003). International Expansion of US Manufacturing Family Businesses: The Effect of Ownership and Involve-ment. Journal of Business Venturing.

- (2012). Building a Family Firm Image: How Family Firms Capitalize on Their Family Ties.

- (2013). Why Do Family Firms Strive for Nonfinancial Goals? An Organizational Identity Perspective.

- Zellweger, Kellermanns, Chrisman, & Chua. (2012). Family Control and Family Firm Valuation by Family CEOs: The Importance of Intentions for Transgenerational Control. Organization Science, 23(3).

- Zellweger, T., & Dehlen, T. (2012). Value is in the Eye of the Owner : Affect Infusion and Socioemotional Wealth among Family Firm Owners. Family Business Review, 25(3), 280-297.