Introduction

Economic and industrial globalization has increased international competition and imposed the need for a continuously evolving legal system, which should both cover and anticipate the multitude of changes in the global economy. A number of trends have contributed to the accelerated globalization of industry and the integration of the economies (Hamner, 2002). The increase in the number and values of mergers and acquisitions comes to sustain this statement and it can be connected to the merger waves which took place during 1983-2016. Given the period of time which is under consideration in this paper, we take into account the last three waves, with their peak in 2007 (1.781 M&As, with a total value of 18.623 billion EUR), 2011 (592 M&As, with a total value of 17.700 billion EUR) and 2016 (1.003 M&As, with a total value of 18.090 billion EUR) (IMAA, 2017). Given the numbers just presented, the need for merger control appeared, in order to propose remedies or prohibit the mergers that hinder competition and are large enough for this effect to be harmful for the society. When determining the competitive impact of a merger, the competition authority takes into account expected synergies put forward by the merging firms (efficiency defense) (Ormosi, 2012; Lagerlöf and Heidhues, 2005). The common factor of the two legal instruments – merger remedies and efficiency defense – in many jurisdictions is that they both have to be initiated by the merging parties. Both instruments will be detailed in the paper.

The European merger control and its importance in granting effective competition in the European Union

The European Union acknowledges the importance of M&As through the regulations which are created and applied for the purpose of facilitating or controlling these types of transactions across the 28 member states. The involved companies encounter many legislative and administrative difficulties in the community. It is therefore necessary, with a view to the completion and functioning of the single market, to lay down community provisions to facilitate the carrying-out of mergers, domestic or cross-border, between various types of companies, governed by the laws of different member states.

There are two major regulations regarding mergers that take place in the EU:

– the Directive 2005/56/EC on the cross-border mergers of limited liability companies, which merge under the national law of the member states. According to the directive, the company taking part in a cross-border merger complies with the provisions and formalities of the national law to which it is subject and at least one of the merging companies is subject to the law of a member state. The directive sets out the procedures for cross-border mergers, including: the common draft terms of the merger, for example, names and registered offices of the merging companies and those proposed for the resulting merged company, including the publication of draft terms; preparation of a report by the management of the merging companies explaining the economic and legal aspects and impact of the proposed merger for the benefit of both members and employees; preparation of an independent expert report on the implications of the merger; approval by the general meeting of the merging companies of the common draft terms (Directive 56/EU, 2005);

– Regulation (EC) No. 139/2004 on the control of concentrations between undertakings, which is referring to the mergers with a community dimension. The law requires that firms proposing to merge apply for prior approval from the Commission, taking into account some criteria: mergers transcend national borders; the combined business exceeds a worldwide turnover of over EUR 5.000 million and a Community-wide turnover of over EUR 250 million, unless each of the undertakings concerned achieves more than two-thirds of its aggregate Community-wide turnover within one and the same Member State (Regulation 139, 2004: art.2).

The two mentioned regulations form together the European Union merger control law. Referring to the second regulation from now on, its main purpose is to ensure that the involved companies will not concentrate enough power so they will affect the free market or harm the interests of community, the consumers, the society as a whole, or the economies in which the companies activate, while granting the effective competition in the EU. Although the main objective of the concentrations of the undertakings is to increase market share, strengthening the negotiation power of the resulting entity, the negative effects on the competitors or customers must be avoided. The most extreme cases which can appear are the situations of monopoly or oligopoly (limited or inexistent competition can lead to higher prices than a market with more participants, where the price is objectively established by the demand and supply). There are authors who consider that mergers are a characteristic of the oligopolistic industries (Hazdeline, 2016; Collie, 2003).

The Merger Remedies in the European Union: Purpose and Implications

The White Paper “Towards more effective EU merger control” from 2014 has drawn attention to the most important change in the new Regulation from 2004: the SIEC test (the new substantive test in European mergers control), which determines whether or not “a concentration which would significantly impede effective competition, in particular by the creation or strengthening of a dominant position, in the common market or in a substantial part of it” (Regulation 39, 2004: Article 2(2) and (3); Röller and de la Mano, 2006). As the result of the assessment of the Commission, the involved companies may propose remedies (also known as commitments) in order to meet specific competition objections raised by the Commission (Cook et al., 2015).

The notion of remedies is found in direct correlation to mergers and acquisitions which must pass a test imposed by a regulatory committee/commission. Mergers remedies are used in competition policy in the European Union and the United States of America seem to follow a relatively similar pattern. In the case of the first, the remedies are split into two categories: structural remedies and behavioral remedies. Structural remedies are referring to divestitures, as preferred approach for solving competitive problems with mergers. On the other hand, behavioral remedies proscribe anticompetitive behavior of the merger companies, and regulate the future conduct of the parties, like changing the prices that a company may practice (Ezrachi, 2006; Cook et al., 2015). Another approach on the remedies belongs to Motta et al. (2002), who consider that the remedies can be categorized in structural (divestiture of an entire ongoing business or only of some assets) and non-structural (constraints on the merged firms’ property rights, engagements by the merging parties not to abuse of their assets). Further, Parker and Balto (2000) distinguish between behavioral measures and contractual arrangements, the latter referring to licensing intellectual property or to closing supply arrangements, which can sustain the concentration and generate future synergies.

If the remedies are proportionate to, and entirely eliminate those competition concerns, they can issue a merger clearance decision, declaring the concentration compatible with EU law. This can be done:

– at the end of phase I investigation, to avoid phase II (Regulation 39, 2004: Article 6(2)). Phase I involves gathering information about the merging companies, and using questionnaires for competitors, customers, and other market participants. The purpose of the questionnaires is to clarify the conditions for competition and the role of the merging companies on the market (European Commission, 2013). For example, in the case of Holcim/Lafarge concentration, the clearance was obtained in phase I, remedies referring to removing overlap between the merging companies in several markets, as a result of the survey (Cook et al., 2015).

– at the end of phase II investigation, to avoid prohibition (Regulation 39, 2004: Article 8(2)). Phase II is an in-depth analysis of the merger’s effect on competition and requests gathering more information than the previous phase. Also, in this case, the Commission asks for an analysis of the expected synergies that the companies would achieve when merged. To be taken into account, the aforementioned synergies must be verifiable, merger specific and passed-on to customers (European Commission, 2013). If these efficiencies are sufficient to out-weigh the anticompetitive effects, the Commission approves the merger. In the absence of efficiency gains, anticompetitive mergers may also receive regulatory approval if parties to the merger offer a settlement package (merger remedy) to the regulatory authority, which modifies the notified merger transaction, as a result of which the anticompetitive effects are eliminated (Ormosi, 2012).

There were voices who have contested the role of the Council Regulation no. 139/2004. As a response to the European Commission’s public consultation with regard to the proposed requirement for notification (the aforementioned “Towards more effective EU merger control”), the form of the notification and the timing for such notifications, many stakeholders have criticized the European Commission’s proposal, inter alia by stating that the acquisitions could be caught by the prohibition of anti-competitive agreements under Chapter 1 “Rules of competition”, Section 1 “Rules applying to undertakings”, article 101 from the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (Balitzki and Pugh, 2016).

For the accuracy of the research, we consider necessary to specify that the M&As which are the subject to the present study were compatible with the EU merger control law (European Commission, 2017).

Research Design and Methodology

Through an empirical, descriptive research, we will study the mergers and acquisitions with a community dimension from the European Union, for the 2005-2016 period of time, aiming at identifying and presenting the characteristics of the studied phenomenon. The data regarding mergers and acquisition were collected from the Zephyr database. One important characteristic of the dataset is that it covers a large fraction of companies, across all industries. Further, it provides information on both listed and unlisted companies. This feature of the data allows for a wide degree of observations in our sample.

The search strategy took into consideration the deal status (completed-assumed, completed-confirmed, rumored, announced), the deal type (merger, acquisition), the geography criterion (European Union enlarged – 28 countries, as acquirer or target or vendor), for 2005-2016 period of time. As a result of the search, a number of 8.105 transactions were generated.

In addition, the following transactions were eliminated:

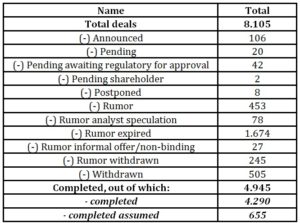

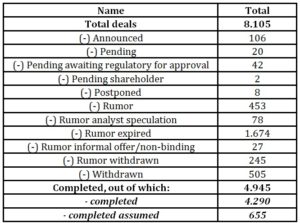

- The transactions with other deal status than “completed-assumed” and “completed” were eliminated (3.160 transactions). The transactions that were eliminated and their status are presented in Table 1.

Table 1: The eliminated transactions from the Zephyr database

Source: Zephyr database 2005-2016 (Bureau Van Dijk)

The sample analyzed consists of 4.945 completed mergers and acquisitions, involving target companies (from the European Union and outside the European Union) and acquirer companies (from the European Union and outside the European Union). This number, relative to the total number of records, represents 61%;

- We eliminate the domestic and cross-border mergers and acquisitions that involved a target and an acquirer company from outside the European Union (641 transactions). These transactions were included in the database because the vendor of the securities was from the European Union, but they are of no interest for our study.

- We eliminate the transactions from 2017 (123 transactions), because the year is not completed, and our research takes into account the 2005-2016 period of time.

The mergers and acquisitions of a controlling interest which are to be analyzed are in number of 4.181 and were applying the provisions of the Regulation no. 139/2004 on the control of concentrations between undertakings.

For the data collection, we used the observation method, considered useful to highlight the characteristics of the participating companies and understand the motivations behind the mergers and acquisitions.

The Results of the Research

The analysis of the M&As with community dimension from the European Union necessitates a wide range of criteria: the geographical distribution of the transactions, from a general view (Eastern and Western Europe) to a particular one (country level, considering the European Union enlarged), the values of the transactions, at European and at country level, the values of the transactions, for target/acquiring companies, according to FTSE classification.

The Geographical Distribution of the M&As In the European Union

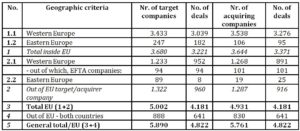

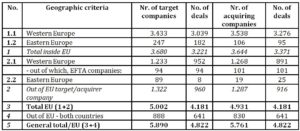

The starting point of our research takes into account the geographical criterion, in order to describe the M&As between companies located in the countries from the European Union and reflects the distribution of the deals and the companies involved (target and acquiring), based on the division between Western and Eastern Europe. Taking into discussion Table 2, we notice the fact that the values and number of transactions are significantly larger for Western Europe, comparative to Eastern Europe. The number of companies involved is later divided between the 28 member countries of the European Union enlarged

Table 2: The number of companies and deals based on the geographical criteria

Source: Own processing after Zephyr database (Bureau Van Dijk)

Table 2 presents the distribution of the companies involved in a merger or an acquisition in which one company is from the European Union (Western or Eastern) and the other one is either from UE or from outside EU (including Iceland, Liechtenstein, Switzerland and Norway). The four countries form together the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), but the last three are united with the European Union in the European Economic Area (EEA), which is an internal market that enables the free movement of goods, services, capital and persons in an open and competitive environment (EEA, 2014). The mergers that involve only companies from these states are controlled by the EFTA Surveillance Authority, which can find infringement of the competition rules, imposes fines and assesses the concentration between undertakings (EEA, 2016). Thus, they don’t apply European regulations on the matter. As a consequence, we took in the analysis the transactions that involved one of these countries and at least one member state of the EU (94 transactions, in which a target company from these countries was involved and 101 transactions, which involved acquiring companies from EFTA):

– Iceland – 2 transactions (one target company and one acquiring company);

– Liechtenstein – 3 transactions (2 target companies and 1 acquiring company);

– Norway – 58 transactions (37 target companies and 21 acquiring companies)

– Switzerland – 132 companies (54 target companies and 78 acquiring companies).

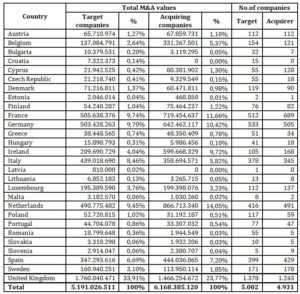

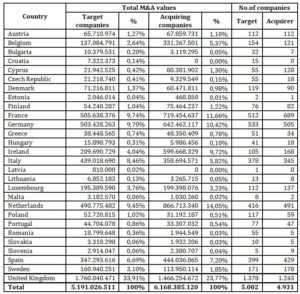

In Table 3 we present the number of companies and the value of M&As (target and acquirer) for the 28 member states of the European Union enlarged.

Table 3: Total value of the transactions and number of companies involved, grouped by target/acquirer – thousand dollars

Source: Own processing after Zephyr database (Bureau Van Dijk)

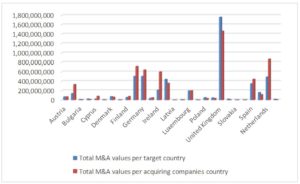

As it can be noticed from Table 3, the most representative values belong to the countries which are among the first members of the European Union (United Kingdom, France, Germany and Netherlands). The percentages of the transactions, in the total, for the mentioned countries represent 33,91% (United Kingdom – target companies), 23,77% (United Kingdom – acquiring companies), 9,74% (France – target companies), 14,05% (Netherlands – acquiring companies), 9,70% (Germany – target companies), and 11,66% (France – acquiring companies)

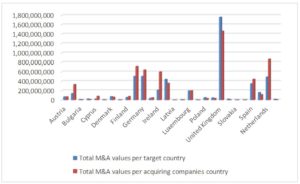

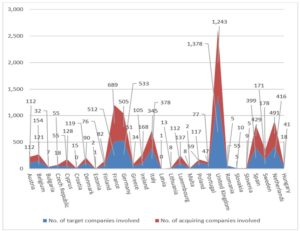

Based on the information in Table 3, we conducted a comparative analysis of the M&A values, taking into account the target companies and the acquiring ones by country, as presented in Figure 1.

Fig. 1: Total values of M&As, for target and acquiring companies, considering the 28 member states of the EU

Source: Own processing

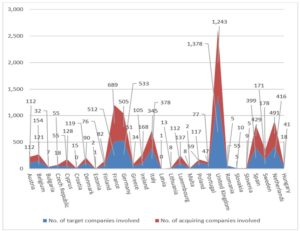

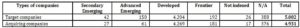

In Figure 2, we reflect the number of companies involved in M&As transactions from the European Union. The numbers are correlated with the ones presented in Table1.

Fig. 2: Number of companies involved in M&As (target and acquirer)

Source: Own processing

As we can observe from Figure 2, the largest number of transactions belongs to the United Kingdom which is followed closely by Germany and France. Thus, the situation is comparative with the one presented in the Table 3.

The Analysis of the M&As According To FTSE Classification

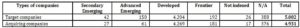

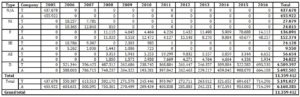

From a different point of view, the M&A phenomenon can be analyzed in a correlation with the classification of the European Union countries, taking into account the FTSE Russell criteria, for 2005-2016 period of time. In Table 4, we find the distribution of the companies from UE according to FTSE classification. At the end of the year 2016, the developed countries were Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Portugal, United Kingdom, Spain, Sweden, Netherlands, advanced emerging were Czech Republic, Greece, Hungary and Poland, frontier economies were Bulgaria, Cyprus, Croatia, Estonia, Lithuania, Latvia, Malta, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia. We have to mention the fact that these countries were analyzed according to their classification in each year for the 2005-2016 period of time.

Table 4: The distribution of the companies from the European Union, according to FTSE classification

Source: Own processing after Zephyr database (Bureau Van Dijk)

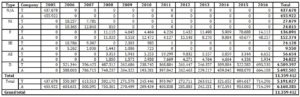

The distribution of the values of M&As for target companies and acquirer companies, according to FTSE classification, is presented in Table 5. The data correspond to the 2005-2016 period of time and the total amounts are correlated with the ones in Table 3.

Table 5: The values of the transactions, grouped by FTSE classification – million dollars –

Legend: D – developed; AE – Advanced emerging; SE – Secondary emerging; F – Frontier; NI – Not indexed; N/A – Not available; T – Target; A – Acquirer.

Source: Own processing after Zephyr database (Bureau Van Dijk)

As it can be noticed, the most significant transactions are made by the developed countries (4.509.397 million dollars for target companies, respectively 5.492.502 million dollars for acquirer companies). For the year 2005, there isn’t a FTSE classification available.

Conclusions

The subject of this study is represented by the mergers and acquisitions published in the Zephyr database for the 2005-2016 period of time. Out of the 8.105 results of our search, we considered as relevant for our topic of research 4.181 transactions, in which companies for the European Union enlarged (28 countries) were involved. As a result of the analysis, we conclude that the largest volume of transactions belongs to the developed countries, especially the United Kingdom, France, Germany and Netherlands, which were between the initiators of the European Union, by signing the Treaty of Rome in 1957. From the 2006, the FTSE Russell classification was available, so we considered timely to present the values for the main categories of economies (developed, advanced emerging, secondary emerging, frontier and not indexed) and we noticed that the most significant transactions, both as in number and value, are those which involved the developed countries.

References

- Balitzki, Anja, Pugh, R. (2016), Mind the Gap? An Analysis from a German Competition Law Perspective of the European Commission’s Proposal to Review Non-Controlling Minority Shareholdings Under European Merger Control Law, International Review of Intellectual Property and Competition Law, 47 (5), 595-616.

- Cook, C., Frisch, S., Novak, V., (2016) Recent developments in EU merger remedies, Journal of European Competition Law & Practice, 7 (5), 341-365.

- Council Regulation (EC) No 139/2004 of 20 January 2004 on the control of concentrations between undertakings, published in the Official Journal of the European Union no. 24/29.01.2004, 1-21

- Directive 2005/56/EC of the European Parliament an of the Council of 26 October 2005 on cross-border mergers of limited liability companies, published in the Official Journal of the European Union no. 310/25.11.2005, 1-9.

- Directive 68/151/EEC on co-ordination of safeguards which, for the protection of the interests of members and others, are required by Member States of companies within the meaning of the second paragraph of Article 58 of the Treaty, with a view to making such safeguards equivalent throughout the Community, published in the Official Journal of the European Union no. 65/14.03.1968, 41-45

- EEA (2014), The EEA Agreement: Final act, Official Journal of the European Union, no. 170, 31-37.

- EEA (2016), The two-pillar structure of the EEA – surveillance and judicial control, Subcommittee on Legal and Institutional Questions. [Online]. [Retreived March 02, 2018], http://old.efta.int/sites/default/files/documents/eea/16-531-the-two-pillar-structure-surveillance-and-judicial-control.pdf

- European Commission (2017), Mergers cases, [Online], [Retrieved February 28, 2018], http://ec.europa.eu/competition/elojade/isef/index.cfm?clear=1&policy_area_id=2

- European Commission (July 2013), Competition: Merger control procedures. [Online]. European Union, [February 20, 2018], http://ec.europa.eu/competition/publications/factsheets/merger_control_procedures_en.pdf

- Ezrachi, A. (2016), Behavioral Remedies in EC Merger Control – Scope and Limitations, World Competition, 29 (3), 459-479.

- Hamner, K. (2002), The globalization of law: merger control and competition law in the United States, the European Union, Latin American and China, Journal of Transnational Law and Policy, 11, 385-402.

- Hazdeline, T. (2017), Mixed pricing in monopoly and oligopoly: theory and implications for merger analysis, New Zealand Economic Papers, 51 (2), 122-135.

- IMAA (2017), Number and value of M&A in Europe, [Online] Institute of Mergers, Acquisitions and Alliances, [March 3, 2018] https://imaa-institute.org/mergers-and-acquisitions-statistics/

- Lagerlöf, J., Heidhues, P. (2005), On the desirability of an efficiency defense in merger control, International Journal of Industrial Organization, 23 (9-10), 803-827.

- Motta, M., Polo, M., Vasconcelos, H. (2002), Merger remedies in the European Union. [Online]. Symposium on “Guidelines for Merger Remedies – Prospects and Principles”, Ecole des Mines, Paris. [Retrieved January 17-18, 2018]. Available: ftp://ftp.igier.unibocconi.it/homepages/polo/RemediesMPV10.pdf

- Ormosi, P. (2012), Claim efficiencies or offer remedies? An analysis of the litigation strategies in EC mergers, International Journal of Industrial Organization, 30 (6), 578-592.

- Parker, R., Balto, D. (2000), The Evolving Approach to Merger Remedies. [Online]. Antitrust Report, [Retrieved February 10, 2018]. Available: https://www.ftc.gov/public-statements/2000/05/evolving-approach-merger-remedies

- Roller, L.H., de la Mano, M. (2006), The Impact of the New Substantive Test in the European Merger Control. [Online]. European Commission. [Retreived February 5, 2018]. Available: http://ec.europa.eu/dgs/competition/economist/new_substantive_test.pdf