Introduction

Relationship marketing has become a core issue for business in the last few decades because there is a continuing growth of service industries in the economy (Lehitnen, 1996), and customer buying patterns are changing rapidly (Buttle, 1999). Building relationship with customers is crucial for business to sustain competitive advantages (Wong and Sohal, 2002). The application of marketing concepts in education setting is rather low, and research from the relationship perspective in education setting is also minimal (Hennig-Thurau et al., 2001). Therefore, there is a need to have research in education setting from the relationship perspective.

Self-financed or private tertiary education has been growing rapidly in the past few years in different parts of the world. In the past, students did not need to pay tuition fees or paid very low tuition fees for tertiary education. In the most recent decades, students have had to pay higher tuition fees. There has been considerable growth in the number of private universities and there are more self-financed programmes in the tertiary education now than ever before. Tertiary education institutions are receiving little or no government funding. A study on student loyalty using relationship perspective is important to self-financed tertiary education (SFTE) industry.

In relationship marketing, a higher level of relationship commitment will lead to higher intention of the parties remaining in a relationship (Gronroos, 1990; Morgan and Hunt, 1994). This present study borrows the concept from marketing literature, and investigates whether relationship commitment has a positive influence on student loyalty, and some of the determinants (relationship benefits, relationship termination costs, shared values, and trust) influencing relationship commitment in the SFTE context.

This study attempts to test the applicability of marketing concepts within the SFTE industry. The main objectives of this study are twofold. Firstly, this study examines the main direct effect of relationship commitment on student loyalty. Secondly, this study also examines the determinants influencing relationship commitment in education context. This empirical study is conducted within the SFTE context in Hong Kong.

Literature Review

Relationship marketing is gaining recognition over the past few decades. The focus has switched from transactional exchange to relationship exchange (Gronroos, 1994).

Relationship marketing is defined as “attracting, maintaining and in multi-service organizations – enhancing customer relationships” (Berry, 1983). Gronroos (1990) described relationship marketing as “to establish, maintain and enhance relationship with customers and other partners” and this is achieved by “mutual exchange and fulfillment of promises”. Morgan and Hunt (1994) extended the definition to include all forms of relational exchange, such as supplier, lateral, buyer and internal, and suggested “establishing, developing and maintaining successful relational exchanges” is relationship marketing. Having good relationship with customers can enhance competitive edge and profits of the company from higher customer loyalty and lower costs in attracting new customers (Berry, 1995).The key objective of relationship marketing is to maintain customer loyalty (Hart and Johnson, 1999). A loyal customer stays in a relationship will do repeat purchase, say positive word-of-mouth, and therefore generate more financial profits to the company (Buttle, 1996; Hart and Johnson, 1999).

Education is people-based. Students are customers of education institutions (Finney and Finney, 2010). A few studies in education field have used Morgan and Hunt’s (1994) model to discuss the relationship between students and their education institutions (Adidam et al., 2004; Holdford and White, 1997; Hennig-Thurau et al., 2001). Building relationship with students is important to enhance student loyalty. A loyal student provides predictable financial resources for tertiary education institutions, especially the self-financed type. This study examines student loyalty using relationship perspective in the context of SFTE.

Student Loyalty

Loyalty is “a deeply held commitment to rebuy or repatronize a preferred product/service consistently in the future” (Oliver, 1999). Early research on customer loyalty has been focused on consumer goods (Gremler and Brown, 1996), with emphasis on behavioral approach (de Ruyter et al., 1998). Behavioral approach refers to repeat purchasing behaviors (Gremler and Brown, 1996; Dick and Basu, 1994). However, the behavioral approach may not give a comprehensive picture of loyalty. With the expansion of service industry in the past few decades, the behavioral approach should be supplemented with the attitudinal approach to reflect relative attitudes towards the product or services (Dick and Basu, 1994). Attitudinal approach is defined as a liking or attitude towards the provider based on satisfactory experience with products or services (Oliver, 1999); customers are more willing to recommend the provider to another customer (Gremler and Brown, 1996).

In the empirical study of Zeithaml et al. (1996), loyalty is found to comprise word-of-mouth and repurchase intention. Repurchase intention implies doing more business with the company in future and considering the company to be the first choice. Word-of-mouth is to say positive things about the company and recommend the company to others.

There is growing interest in studying student loyalty, and student loyalty has become an important concern for tertiary education (Hennig-Thurau et al., 2001; Marzo-Navarro et al., 2005). Some studies on student loyalty (such as Helgesen and Nesset, 2007; Nguyen and LeBlanc, 2001; and Rowley, 2003) have adopted the two aspects of loyalty identified by Zeithaml et al. (1996), that is repurchase intention and word-of-mouth. This study adopts the repurchase intention aspect as student loyalty because this study aims to find out whether the existing associate degree and higher diploma students of SFTE institutions would continue to pursue bachelor degree courses at their current institutions in future.

According to Reichheld (1996), an existing customer cannot be replaced by a new customer, and it is expensive to attract a new customer. On average, a company spends two to twenty-five times as much on attracting a new customer relative to retaining an existing customer (Nauman and Giel, 1995). Customer loyalty is crucial to keep cost low. In education, retaining students can provide solid financial support to the education institution; a loyal student may recommend his/her education institution to friends, and may also continue to support the education institution via donations, financial support or offering placements to existing students after graduation (Hennig-Thurau et al., 2001). Since student loyalty is important, it is worthwhile to examine a key determinant of student loyalty, the relationship commitment, in the next section. Relationship commitment stabilizes behaviors over time, irrespective of the circumstances (Scholl, 1981), and this is a key component of long-term loyalty (Morgan and Hunt, 1994). Some recent studies emphasize the importance of relationship commitment to enhance student loyalty because education is a service and relationship commitment in service industry helps build relationships which, in turn, enhances loyalty. Relationship commitment is found to be a key factor affecting students’ cooperation and propensity to leave in western government-funded tertiary education context (Adidam et al., 2004; and Holdford and White, 1997).

Relationship Commitment

In organizational behavior literature, commitment comprises affective (emotional) and cognitive (calculative) aspects (Allen and Meyer, 1990; O’Reilly and Chatman, 1986). Many marketing scholars borrow the concept of organizational commitment to understand the nature of customer commitment (Fullerton, 2003; Gruen et al., 2000). Affective commitment is customers’ emotional bonding and sense of belonging to the company and customers’ attachment to the company (Fullerton, 2005; Mattila, 2004; Gruen et al., 2000). Cognitive commitment arises from a cognitive evaluation of gains and losses, and benefits and costs of a continued relationship with the company (Geyskens et al., 1996). Cognitive commitment is the extent of the need to maintain a relationship due to significant perceived termination or switching costs (Venetis and Ghauri, 2004).

In service marketing literature, “relationships are built on the foundation of mutual commitment” (Berry and Parasuraman, 1991). In relationship marketing literature, relationship commitment is described as “an enduring desire to maintain a valued relationship” (Moorman et al., 1992). Relationship commitment is considered as a central construct in relationship marketing literature (Morgan and Hunt, 1994), and is defined as “an exchange partner believing that an ongoing relationship with another is so important as to warrant maximum efforts at maintaining it; that is, the committed party believes the relationship is worth working on to ensure that it endures indefinitely” (Morgan and Hunt, 1994). Relationship commitment entails a desire to develop a stable relationship and confidence in the stability of the relationship (Anderson and Weitz, 1992).

This study adopts Moorman et al.’s (1992) concept of relationship commitment as an enduring desire to maintain a valued relationship, and examines relationship benefits, relationship termination costs, shared values and trust as the four key factors affecting relationship commitment because these four factors have been found to have impact on relationship commitment in the context of western government-funded tertiary education (Adidam et al., 2004; Holdford and White, 1997). The following sections examine these four factors in details.

Relationship Benefits

The ability to provide superior benefits and value to customers is a prerequisite when establishing relationship with customers (Ravald and Gronroos, 1996). Morgan and Hunt (1994) examined the relationship between automobile tire retailers and suppliers, a business to business relationship, and said relationship benefits obtained by retailers include product profitability, customer satisfaction, and product performance. Relationship benefits refer to the quality of services and goods relative to other suppliers. Relationship benefits are the superior benefits provided to customers, and these superior benefits are highly valued by customers.

The benefits customers receive from a relationship are risk-reducing benefits and social benefits (Berry, 1995). Bitner (1995) conceptualized relationship benefits in four aspects: reducing stress, simplifying one’s life, enjoying social support system, and precluding the need to change. Benefits addressed by Berry (1995) and Bitner (1995) can be generalized into two types: functional benefits and social benefits (Beatty et al., 1996). In a recent study of relationship benefits in the retail banking industry of Greece, Dimitriadis (2010) suggested that the five types of benefits are: competence, benevolence, special treatment, social and convenience.

Relationship benefits generate positive impact on relationship outcomes, such as, continuation of a relationship (Gwinner et al., 1998; Patterson and Smith, 2001), site commitment (Park and Kim, 2003), commitment to the service business (Hennig-Thurau et al., 2002), commitment in online retailing context (Mukherjee and Nath, 2007), and satisfaction in retail banking (Dimitriadis, 2010; Molina et al., 2007).

In education context, Adidam et al. (2004), and Holdford and White (1997) suggested that students will continue their relationship with their school if the school offers superior benefits in terms of education quality, location, cost of tuition, internship opportunities, better placements and networking opportunities. The higher the relationship benefits obtained by the students, the higher will be the relationship commitment of students to their education institution. This study follows Morgan and Hunt’s (1994) conceptualization of relationship benefits, which has been used by Adidam et al. (2004) and Holdford and White (1997).

Relationship Termination Costs

“Termination costs are all expected losses from termination and result from the perceived lack of comparable potential alternative partners, relationship dissolution expenses, and/or substantial switching costs” (Morgan and Hunt, 1994). Switching costs are defined as the costs of switching from one supplier to another (Burnham et al., 2003; Wathne et al., 2001). Besides, switching costs are conceptualized as customers’ perceptions of the magnitude of additional costs required to terminate the current relationship and secure an alternative (Porter, 1980; Jackson, 1985).

“Expected termination costs lead to an ongoing relationship being viewed as important, thus generating commitment to relationship” (Morgan and Hunt, 1994). Though Morgan and Hunt (1994) see switching costs to be of an economic nature only, switching costs may also comprise psychological and emotional costs (Sharma and Patterson, 2000). Switching costs mean the costs of switching including psychological costs, time and money (Dick and Basu, 1994). Furthermore, the perception of searching costs, such as time and effort to be incurred in selecting a new supplier is also a kind of switching cost (Sharma and Patterson, 2000).

Burnham et al. (2003) described switching costs from three perspectives: procedural switching costs, financial switching costs,and relational switching costs. White and Yanamandram (2007) proposed switching costs include uncertainty costs, pre-switching costs, set-up costs, post-switching costs, and benefit/loss costs.

Findings of Vasudevan et al. (2006), Burnham et al. (2003), and Patterson and Smith (2001) suggest that relational switching cost that involves psychological and emotional discomfort due to breaking of bonds and loss of identity is positively associated with commitment. White and Yanamandram (2007) suggested that in business-to-business service sector, customers are motivated to commit to existing relationships because of the high switching costs as described in the above section.

In education context, Adidam et al. (2004) studied the relationship between students and their school and defined relationship termination costs as the perception of net losses (financial, emotional, or time) that may result from dissolution of the relationship. The perceived costs to a student include both economic and non-economic sides of switching costs. Therefore, it might be the loss of friendships or loss of credits on switching to another educational institution. The losses cannot be made good by the other supplier. Their findings suggest that relationship termination costs have a positive impact on relationship commitment in western government- funded tertiary education institutions. The present study adopts conceptualization of relationship termination costs in Porter (1980).

Shared Values

Different studies have used different names to describe shared values. For instance, Levin (2004) used shared perspective to investigate shared vision and shared language of two parties, while Orr (1990) and Monteverde (1995) used shared perspective to investigate shared language and shared narratives. Tsai and Ghoshal (1998) used shared vision to refer to the common goals or aspirations the organization members share which help members to communicate and exchange ideas freely. According to Schein (1990), values shared between two parties are the underlying assumption.

Further, there is a broader interpretation of shared values by Morgan and Hunt (1994). Shared values are defined as “the extent to which partners have beliefs in common about what behaviors, goals and policies are important or unimportant, appropriate or inappropriate, and right or wrong” (Morgan and Hunt, 1994). It means two parties are having similar perceptions about how to interact with others to enhance their communications and avoid misunderstanding. Shared values will bring more opportunities for two parties to exchange their ideas (Tsai and Ghoshal, 1998). In service industry, shared values is the extent to which a service provider and a client have common beliefs in what services are important or unimportant, appropriate or inappropriate, and right or wrong (Morgan and Hunt, 1994; Levin, 2004).

Parties that share similar values about appropriate behaviors, goals and policies are more likely to be committed to a relationship (Morgan and Hunt, 1994; Holdford and White, 1997; Adidam et al. 2004). In education, Holdford and White (1997) found that students who shared the same goals, ideals and codes of conduct with their school were more likely to commit to a relationship with the school. Adidam et al. (2004) found that the more the staff and students have similar concerns and ideas on important issues, such as work-load, learning behavior and assessments, the more the students will be committed to the relationship. Both studies suggest that the construct of shared values is one of the factors affecting relationship commitment in western government-funded tertiary education. This study adopts the conceptualization of shared values in Morgan and Hunt (1994).

Trust

Trust has been defined in classical studies of psychology, sociology and economics, as relying on one’s word, promise, oral or written statement (Rotter, 1967), expecting the occurrence of an event (Deutsch, 1958), and making beneficial decisions (Gambetta, 1988). The definition of trust has evolved over time and numerous interpretations have been found in marketing literature. Many researchers consider trust a kind of belief or confidence (Crosby et al., 1990; Moorman et al., 1992; Morgan and Hunt, 1994). Besides, trust is related to benevolence, which refers to the service provider’s motives and intentions toward the client (Crosby et al., 1990; Doney and Cannon, 1997).

Reliability is a word usually used in the definition of trust (Schurr and Ozanne, 1985; Crosby et al., 1990; Moorman et al., 1992; Morgan and Hunt, 1994). Reliability refers to one’s promise (Schurr and Ozanne, 1985), and it is also about being consistently good in performance (Moorman et al., 1992; Morgan and Hunt, 1994).Morgan and Hunt (1994) use reliability and integrity together to define and conceptualize trust, and define trust as “when one party has confidence in an exchange partner’s reliability and integrity.” A trustworthy party is one that is considered reliable and having high level of integrity and associating qualities of competence, consistence, fairness, honesty, responsibility, helpfulness and benevolence.

Trust enhances commitment to a relationship by reducing transaction costs in an exchange relationship, reducing risk perceptions associated with the partner, and increasing confidence that short term inequities can be resolved in the long run. Trust has been found to be a factor affecting commitment in many previous studies (Morgan and Hunt, 1994; Gannesan, 1994; Moorman, Zaltman and Desphande, 1992; Kassim and Abdulla, 2006; Liang and Wang, 2007).

A few studies have adopted the Morgan and Hunt (1994) model to study the relationship between students and education institutions, such as Hennig-Thurau et al. (2001), Holdford and White (1997), and Adidam et al. (2004). These studies conceptualize trust as confidence in an exchange partner’s reliability and integrity.

They are based on personal experiences individual students have had with their education institutions. The findings in these studies suggest that trust is one of the factors affecting relationship commitment in government-funded tertiary education.This study follows the abovementioned studies in education, and conceptualizes trust as the one used by Morgan and Hunt (1994).

Relationship between Shared Values and Trust

Morgan and Hunt (1994) suggested that the construct of shared values is an antecedent to relationship commitment, as well as trust. Perceptions of similar values between partners increase the perceived ability of partners to predict the other’s behavior and motives, and therefore increase trust. Higher shared values between partners lead to a higher level of trust.Similar values on what are the right things to do and what are the things worth doing influence one’s choices and actions (Conner and Backer, 1975), and shared values are taken as an antecedent of trust development. Shared values are the key antecedent of trust in online retailing context (Mukherjee and Nath, 2007).

In the government-funded tertiary education context, Adidam et al. (2004) and Holdford and White (1997) also suggested that the construct of shared values is positively associated with trust. When teachers and students are having similar values such as a strong work ethic, students are more likely to attribute challenging examination questions and assignments to the work ethic rather than less desirable attributions.

Having reviewed the concepts of student loyalty, relationship commitment, relationship benefits, relationship termination costs, shared values and trust, the next section examines the research model and hypotheses.

Research Model and Hypotheses

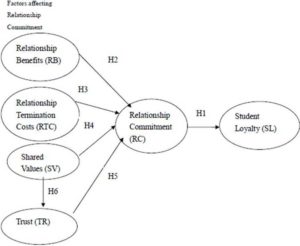

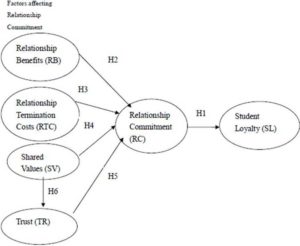

This study proposes the following conceptual model which links student loyalty, relationship commitment, and four factors affecting relationship commitment (Figure1). The research model has two main features. Firstly, it examines the main direct effect of relationship commitment on student loyalty. Secondly, it investigates the factors (relationship benefits, relationship termination costs, shared values, and trust) affecting relationship commitment. This section presents the research model and hypotheses.

Relationship Commitment as a driver of Student Loyalty

Commitment is a key element of long-term loyalty (Morgan and Hunt, 1994). It is found to have positive impact on customer loyalty (Verhoef et al., 2002; Fullerton, 2005). Numerous studies in business setting have validated the commitment-loyalty link (Macintosh and Lockshin, 1997; Caceres and Paparoidamis, 2007; Amine, 1999; Dimitriades, 2006; Wetzels et al., 1998). In tertiary education, enhancing student commitment to the education institution is a top priority of institutions’ managements. Adidam et al. (2004) and Holdford and White (1997) suggested that relationship commitment has a positive impact on cooperation between students and the education institution, and a negative impact on propensity to leave the education institution. Based on the aforesaid literature, the first hypothesis is formulated:

H1: Students’ relationship commitment to the education institution has a significant positive impact on student loyalty.

Relationship Benefits as a driver of Relationship Commitment

Relationship benefits have positive effects on relationship outcomes, such as commitment to service business (Hennig-Thurau et al., 2002), commitment to continue in a relationship (Gwinner et al.,1998), and philanthropists’ commitment to non-profit organizations (MacMillan et al., 2005). Adidam et al. (2004) and Holdford and White (1997) suggested that students will continue their relationship with their education institution if the education institution offers superior benefits in terms of education quality, location, cost of tuition, internship opportunities, better placements and networking opportunities. The higher the relationship benefits obtained by the students, the higher the relationship commitment of students to their education institution will be. Using the aforesaid literature, the second hypothesis is formulated:

H2: Students’ perception of relationship benefits has a significant positive impact on relationship commitment.

Figure 1. Conceptual Model of Relationship Commitment on Student Loyalty

Relationship Termination Costs as a driver of Relationship Commitment

The relationship termination costs-relationship commitment link has been validated in numerous studies in business setting (Porter, 1980; White and Yanamandram, 2007; Dwyer et al., 1987; Sharma and Patterson, 2000). Adidam et al. (2004) defined relationship termination costs as the perceptions of financial, emotional, or time losses that may result from dissolution of the relationship. The costs perceived by students include both economic and non-economic sides of switching costs; therefore, it might be the loss of friends or loss of credits that may have to be incurred when switching to another education institution. Their findings suggest that relationship termination costs have a positive impact on relationship commitment. Based on the aforesaid studies, the third hypothesis is formulated:

H3: Students’ perceptions of relationship termination costs havea significant positive impact on relationship commitment.

Shared Values as a driver of Relationship Commitment

The more the parties share information and communicate, the stronger the relationship between the parties (Anderson and Weitz, 1989; Anderson and Narus, 1990). Shared values are found to have positive impact on relationship commitment (Morgan and Hunt, 1994). Holdford and White (1997) found that students who shared the same goals, ideals and codes of conduct with the education institution were more likely to commit to a relationship with the education institution. Adidam et al. (2004) found that the more the staff and students had similar ideas and positions on important issues, such as work-load, learning behavior and assessments, the more committed the students were to the relationship. Both studies showed that the construct of shared values is one of the determinants of relationship commitment. Based on the aforementioned literature, the fourth hypothesis is formulated:

H4: Students’ perceptions of shared values have a significant positive impact on relationship commitment.

Trust as a Driver of Relationship Commitment

Numerous studies in business setting have validated the link between trust and relationship commitment. Morgan and Hunt (1994) found that trust was one of the determinants of relationship commitment. In a business-to-business environment, trust is an element in building relationship commitment between companies (Caceres and Paparoidamis, 2007). Adidam et al. (2004) and Holdford and White (1997) suggested that trust is one of the determinants of relationship commitment in government-funded tertiary education. Using the aforesaid studies, the fifth hypothesis is formulated:

H5: Students’ trust in the education institution has a significant positive impact on relationship commitment.

Shared Values as a driver of Trust

Previous studies have indicated that the more the values shared between partners, the higher the level of trust created between them. Morgan and Hunt (1994) found that perceptions of similar values shared between partners increase the trust among partners. Adidam et al. (2004) and Holdford and White (1997) suggested that the construct of shared values is positively associated with trust in government-funded tertiary education. Based on the aforesaid studies, the sixth hypothesis is formulated:

H6: Students’ perceptions of shared values have a significant positive impact on trust.

Research Design and Method

This study has a confirmatory approach because the hypotheses in this study are developed on the basis of theories found in previous studies in business settings and government-funded education institutions. The aim of this study is to investigate whether the marketing concepts are supported in SFTE institutions by empirical data. This study uses the questionnaire survey method to collect primary data from students. Respondents of pilot test also indicated that students were comfortable with filling in the questionnaires. This section discusses sampling and data collection, and measurements of constructs.

Sampling and Data Collection

The present study aims to investigate the relationship between relationship commitment and student loyalty and factors affecting relationship commitment in SFTE institutions. The researcher wants to find out whether the current self-financed associate degree and higher diploma students will continue their bachelor degree studies at their current tertiary education institutions. For the purpose of this study, a SFTE institution was identified from the list of tertiary education institutions available on the website of Education Bureau of the HKSAR Government (http://www.edb.gov.hk/). Enrolment of students in this institution accounted for 11.5% (2008/09) of the total number of self-financed associate degree and higher diploma students in all the 21 institutions in Hong Kong. This institution was approached and it agreed to allow the researcher to administer the questionnaire survey to associated degree and higher diploma students at the campus. Convenience sampling technique was used to approach the students because students are the direct customers of education.

Trained student helpers distributed the questionnaire together with a covering message explaining the purpose of the study to students in the identified SFTE institution. A personally administered questionnaire allows student helpers to introduce the survey, provide clarifications on the spot to respondents, and collect the completed questionnaire immediately; it is also less expensive and less time-consuming than interviews because the questionnaires can be distributed to a large number of individuals simultaneously (Cavana et al., 2001).

Participation in the survey was voluntary. The mass survey was conducted in April 2010. 480 questionnaires were distributed. After discarding all invalid questionnaires, 444 valid questionnaires were collected. SPSS 13.0 was used to examine the descriptive frequencies. 60.4% of the respondents were female. 98.2% of the respondents were in the age range of 18 to 25. 40.1% of the respondents were associate degree students and 59.9% were higher diploma students. Almost half of the respondents were studying business courses. 49.3% of the respondents were from the business division, 23.9% were from science and technology division, and 26.8% were from communication and social science division.

Measurements of Constructs

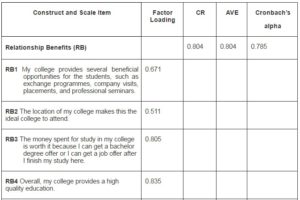

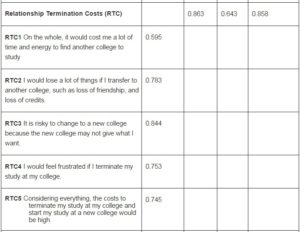

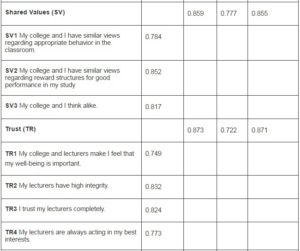

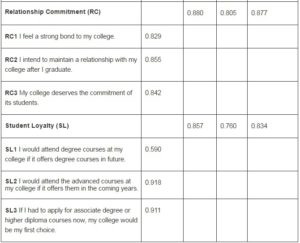

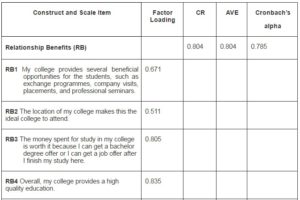

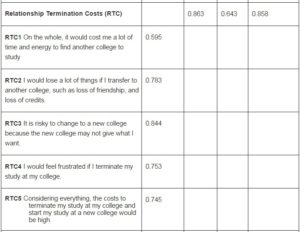

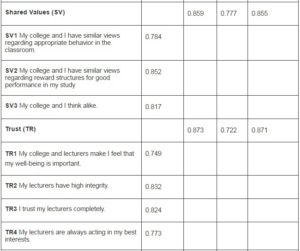

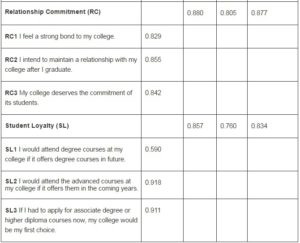

The measures of student loyalty, relationship commitment, relationship benefits, relationship termination costs, shared values and trust relied on existing validated scales in previous research. Table 1 provides the details of these measurements. The 7-point Likert-type scales were anchored by 1 (strongly disagree) and 7 (strongly agree) for all 22 items.

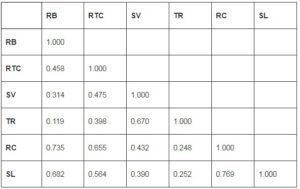

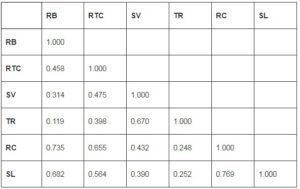

Student loyalty was measured with three items adopted from a previous study in education context (Nguyen and LeBlanc, 2001). Relationship commitment was measured with three items, and trust was measured with four items, adopted from Holdford and White (1997), a previous study in education context. Four items of relationship benefits and three items of shared values were adopted from previous studies in education context (Adidam et al., 2004; and Holdford and White, 1997). This study considers both economic and non-economic sides of relationship termination costs, and 5 items were adopted from Sharma and Patterson (2000). Some wordings are modified to fit the education context. Table 2 provides correlation matrix of the constructs.

Analysis and Results

This study employed two steps to assess the measurement and structural model.

Measurement Model Testing and Results

The confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) reveals that the chi-square for the overall model is 648.15 (df = 194, p-value = 0.00). Other fit indices, including the comparative fit index (CFI = 0.968), normed fit index (NFI = 0.955), relative fit index (RFI = 0.946), incremental fit index (IFI = 0.968), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA = 0.075), are satisfactory because they are better than recommended values. Therefore, the proposed model provides a reasonable explanation of the observed covariance among the six constructs.

Reliability and validity were assessed to ensure the information is trustworthy. The reliability coefficients of the six constructs range from 0.785 to 0.877 (Table 1). These statistics show that the measuring instruments used in this study have high reliability (internal consistency) coefficients for the sample of respondents.

The satisfactory alpha estimates obtained from the reliability test (Table 1) also demonstrate good convergent validity. Further, the significantly high and moderate loadings of indicators in the measurement model also provide sufficient evidence of convergent validity of the constructs, as shown in Table 1 (Anderson & Gerbing, 1998; Dabholker, Thorpe & Rentz, 1996; Patterson et al., 1997). In addition, the moderate to high correlations between constructs (Table 2) also suggest that the measures of the model display a certain degree of convergent validity. (Cronin & Taylor, 1992; Quester & Romaniuk, 1997).

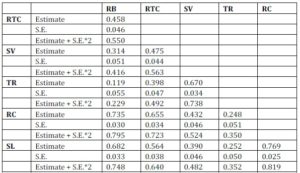

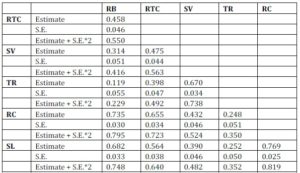

Calculations of the covariance matrix produced values ranging from 0.229 to 0.819 for each pair of construct, which are lower than the recommended level of 1.0 (Dabholkar et al., 1996; Koerner, 2000) (Table 3). Therefore, the result suggests that the constructs are statistically distinct within the CFA model, and provides evidence of discriminant validity.

Table 1 Construct Measures and Confirmatory Factor Analysis Results

Note: All estimates were significant (p<0.001), CR = composite reliability, AVE = average variance extracted

Note: All estimates were significant (p<0.001), CR = composite reliability, AVE = average variance extracted

Table 2 Correlation Matrix of Constructs

Note: All correlations were significant (p<0.05)

Table 3 Covariance Matrixes of the Six Constructs

Another test for discriminant validity is average variance extraction (AVE) (Dabholkar et al., 1996). The results of AVE calculated for the CFA model are presented in Table 1. All values of AVE range from 0.625 to 0.805, exceeding the recommended level of 0.5 (Hair et al., 1998). In conclusion, the results confirm the discriminant validity of the constructs in CFA model. Therefore, the measurement model meets all psychometric property requirements.

Overall Structural Model: Path Analysis and Hypothesis Testing

Using LISREL 8.8, Structural Equation Model (SEM) was used to analyze the structural model (Figure 1). Except for the low p-value and relatively high Chi-square/df ratio (p-value = 0.00, df = 200, Chi-square/df = 3.4), most of goodness of fit indices, including NFI, RFI, IFI and CFI, range from 0.945 to 0.966. All are well above the recommended level of 0.90. In addition, RMSEA of the proposed model is 0.076, which is below the minimum requirement of 0.10 and within the fair fit range of 0.05 to 0.08. These goodness of fit indices indicate that the structural model represents the data structure well.

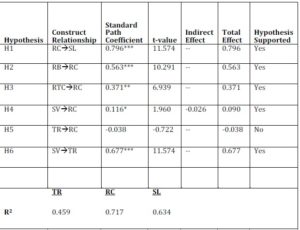

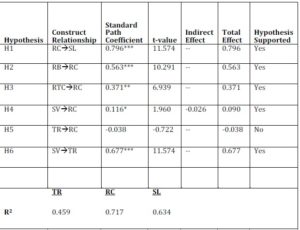

R2 values, path coefficients, and their statistical significance for fitted hypothesized model, and the results of direct, indirect, and total effects of the model are shown in Table 4. R2 values of the constructs are high, ranging from 0.459 to 0.717 (trust, student loyalty, and relationship commitment), which provide adequate evidence of the predictive ability of the model. Each hypothesis was tested by examining path coefficient. All structural paths except hypothesis H5 are significant at the 0.05 level, which suggests that Trust (TR) shows insignificant direct effect on Relationship Commitment (RC), and, therefore, hypothesis H5 should be rejected in the subsequent analysis. In contrast, Relationship Benefits (RB), and Relationship Termination Costs (RTC) show strong influence on Relationship Commitment (RC), as indicated by high to moderate standardized coefficients 0.563 and 0.371, respectively. Hypotheses H2 and H3 are supported by empirical evidence. Shared Values (SV) has a small direct effect (standardized coefficient 0.116) on Relationship Commitment (RC), and an indirect effect through Trust (TR), which gives a total effect of 0.090. Hypothesis H4 is supported. In addition, the high standardized coefficient of 0.677 indicates that Shared Values (SV) has a significant and strong influence on Trust (TR). Hypothesis H6 is supported. Finally, the high standardized coefficient of 0.796 indicates that Relationship Commitment (RC) has a significant and strong influence on the ultimate endogenous variable Student Loyalty (SL). Hypothesis H1 is supported. It can therefore be concluded that hypotheses H1, H2, H3, H4 and H6 are strongly supported with empirical evidence in the proposed model.

Table 4 Testing of the Hypotheses

* indicates significant at p<.05 level;

** indicates significant at p<.01 level;

*** indicates significant at p<.001 level.

Discussion

Having good relationship with customers will enhance competitive edge and increase financial benefits of the company from higher customer loyalty and lower costs of attracting customers (Berry, 1995). Extant research from the relationship perspective in education setting is minimal (Hennig-Thurau et al., 2001). Therefore, this study is one of the earliest attempts to test relationship marketing concepts in education context.

Self-financed or private tertiary education has beengrowing rapidly in the recent past all over the world. Students have to pay high tuition fees for tertiary education. The operation of self-financed education institutions is similar to running a business company, and the students are considered as customers. Managements of SFTE institutions have to focus on enhancing student loyalty in order to get sufficient revenue for running the institutions. Relationship commitment is found to be positively associated with loyalty in business environment in previous studies, such as Caceres and Paparoidamis (2007), Amine (1999), and Morgan and Hunt (1994). In the limited previous research in education environment, relationship commitment is found to be a key factor affecting students’ cooperation and propensity to leave (Adidam et al., 2004; Holdford and White, 1997). This study, therefore, has investigated the association between relationship commitment and student loyalty in SFTE.

As relationship commitment is found to be important in enhancing loyalty, a better understanding of factors affecting relationship commitment is also crucial. Based on literature review, relationship benefits, relationship termination costs, shared values, and trust were chosen as the determinants of relationship commitment. A hypothesized model investigating the association between relationship commitment and student loyalty, and determinants of relationship commitment, is proposed in this study.

The overall structural model is supported by empirical data. Most of the hypothesized relationships are supported; only one hypothesis is not supported (Table 4). Based on SEM analysis of the proposed model (Figure 1), the results of this study support the main direct effect of relationship commitment on student loyalty, and support the direct effects of relationship benefits, relationship termination costs, and shared values on relationship commitment. The results also support that shared values have influence on trust.

However, unlike the common finding in most relationship marketing literature that trust is a determinant of relationship commitment, the direct effect of trust on relationship commitment is found to be insignificant. This result provides a new insight into the relationship marketing area in SFTE context and to the managements of self-financed educational institutions. The primary objective of the sub-degree students is to further their studies in degree courses. Having trust in the education institution does not mean that the students can have a higher chance of getting degrees and, therefore, trust is found to have no relationship with relationship commitment in SFTE.

Relationship building helps education institutions gain competitive advantages. This empirical research provides meaningful and useful contributions to theoretical development of relationship marketing concepts in education context and education management.

Managerial Implications

The findings of this study contribute useful managerial insights for education providers in the SFTE industry. This study shows that relationship commitment has a substantive and positive effect on student loyalty in the SFTE industry. Education providers have to focus on enhancing relationship commitment in order to increase student loyalty.

With the findings of this study, education providers can gain a better understanding of determinants affecting relationship commitment, and thus can plan accordingly to nurture them. Relationship benefits, relationship termination costs, and shared values all positively influence relationship commitment in SFTE, while trust does not. The primary intention of self-financed students is to get degrees, and having trust in education institution does not mean they can get degrees.

Education providers can use the results of the path analysis to understand the preferences of self-financed students (customers) and allocate resources to enhance the determinants affecting the students’ relationship commitment which will increase the students’ loyalty. This will also ensure effective use of education institutions’ resources and focus.

The construct of relationship benefits is the most influential determinant of relationship commitment in the SFTE industry. Relationship benefits include education quality, placements, networking options, internship opportunities, professional seminars and talks, company visits, location of the institution, and cost of tuition, etc. (Adidam et al., 2004). Education providers have to promote and improve these perceived relationship benefits on a continuous basis in order to raise the relationship commitment of students.

The construct of relationship termination costs is the next influential determinant. This provides signals to education providers that students’ perceived costs, both economic and non-economic, are the important consideration in building relationship commitment with the education institution. Education providers have to increase students’ relationship termination costs in order to raise their relationship commitment with the education institution.

The construct of shared values is also a determinant of relationship commitment in the SFTE industry. The more the staff and students have similar values on education issues, such as learning behavior, assessments, and work-load, the more the students will be committed to the relationship with the educational institution (Adidam et al., 2004).

Trust is not a determinant of relationship commitment in the SFTE industry. Therefore, education providers should increase focus on, and allocate more resources to other important factors (relationship benefits, relationship termination costs, and shared values) in order to raise the students’ relationship commitment with education institution.

Limitations and Future Research

The study results have various limitations which indicate several potential areas for future research works. Firstly, the sample was drawn from only one identified SFTE institution. To enhance generalizability of findings, the study can be extended to other SFTE providers. Besides, the study can also be conducted in other countries and other environments.

Secondly, future research can consider conducting a longitudinal study to trace the changing preferences and behaviors of students (customers). The use of multiple time frames allows researchers to track behavioral intentions of students (customers) over time.

Thirdly, future research can consider studying other potential outcomes of relationship commitment. Repurchase intention aspect of loyalty is just one outcome. Other potential outcomes can include students’ willingness to recommend their education institutions to others, and propensity to leave the education institution, and co-operation with lecturers.

Fourthly, the direct effects of relationship benefits, relationship termination costs, and shared values on student loyalty, the mediating role of effect of relationship commitment on student loyalty, and applicability of the KMV model of Morgan and Hunt (1994) in SFTE environment have not been covered in this study. Future research can consider studying these areas.

Finally, the present study has investigated the effect of relationship commitment on student loyalty, and the determinants of relationship commitment. There are some unexplained portions which have not been considered in this study. Future research can consider adding other factors affecting student loyalty, such as, image, brand, reputation, and satisfaction; and adding other factors affecting relationship commitment, such as service quality, and dependence.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

References

Adidam, P. T., Bingi, R.P. & Sindhav, B., (2004). “Building Relationships between Business Schools and Students: An Empirical Investigation into Student Retention,” Journal of College Teaching & Learning, Vol. 1, No. 11, pp.37-48.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Allen, N. & Meyer, J. (1990). “The Measurement and Antecedents of Affective, Continuance and Normative Commitment to the Organization,” Journal of Occupational Psychology, Vol. 63, No. 1, pp.1-18.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Amine, A. (1999). Le Comportement du Consommateur Face aux Variables d’actions Marketing, EMS, Caen.

Anderson, J. C. & Gerbing, D.W., (1988). “Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: a Review and Recommended Two-Step Approach,” Pyschological Bulletin, Vol. 103, pp.411-423.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Anderson, J.C. & Narus, J.A. (1990). “A Model of Distributor Firm and Manufacturer Firm Working Partnerships,” Journal of Marketing.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Anderson, E. & Weitz, B.A., (1992). “The Use of Pledges to Build and Sustain Commitment in Distribution Channels,” Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 29, No. 1, pp.18-34.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Anderson E., and Weitz B.A., (1989). “Determinants of Continuity in Conventional Industrial Channel Dyads,” Marketing Science, Vol. 8, No. 4, pp.310-323.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Beatty S. E., Mayer M., Coleman J. E., Reynolds K. E. & Lee J., (1996). “Customer-Sales Associate Retail Relationships,” Journal of Retailing, Vol. 72, No. 3, pp.223-247.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Berry, L. L. (1995). “Relationship Marketing of Services – Growing Interest, Emerging Perspectives,” Journal of the Academy of Marketing, Vol. 23, No. 4, pp.236-245.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Berry, L.L. (1983). “Relationship Marketing in Berry L.L., Shostack G.L., and Upah G.D. (Eds),” Emerging Perspectives on Services Marketing, pp.25-28.

Berry, L.L. & Parasuraman, A. (1991). Marketing Services: Competing Through Quality, New York: Maxwell Macmillan.

Google Scholar

Bitner, M. J. (1995). “Building Service Relationships: Its All about Promises,” Journal of Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. 23, No. 4, pp.246-251.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Burnham ,T.A., Frels, J.K. & Mahajan, V. (2003). “Consumer Switching Costs: A Typology, Antecedents, and Consequences,” Journal of Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. 31, No. 2, pp.109-126.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Buttle, F. (1999). “The SCOPE of relationship management,” International Journal of Customer Relationship Management, Vol. 1, No. 4, pp.327-336.

Buttle, F. (1996). “SERVQUAL: Review, Critique, Research Agenda,” European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 30, No. 1, pp.8-32.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Caceres, R.C. & Paparoidamis N.G. (2007). “Service Quality, Relationship Satisfaction, Trust, Commitment and Business-To-Business Loyalty,” European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 41, No. 7 & 8, pp.836-867.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Cavana, R.Y., Delahaye, B.L. & Sekaran, UMA (2001). Applied Business Research: Qualitative and Quantitative Methods, John Wiley & Sons Australia, Ltd.

Cronin, J.J. & Taylor, S.A. (1992). “Measuring Service Quality: A Re-Examination and Extension”. Journal of Marketing, Vol. 56, No. 1, pp.55-68.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Crosby, L.A., Evans, K.R. & Cowles, D. (1990). “Relationship Quality in Services Selling: An Interpersonal Influence Perspective,” Journal of Marketing, Vol. 54, July, pp.68-81.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Dabholkar, P.A., Thorpe, D.I. & Rentz, J.O. (1996). “A Measure of Service Quality for Retail Stores: Scale Development and Validation,” Journal of Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. 24, No. 1, pp.3-16.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

de Ruyter, K., Wetzels, M. & Bloemer, J. (1998). “On the Relationship between Service Quality, Service Loyalty and Switching Cost,” International Journal of Service Industry Management, Vol. 9, No. 5, pp.436-453.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Deutsch, M. (1958). “Trust and Suspicion,” Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol. 2, No. 4, pp.265-279.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Dick, A. & Basu, K. (1994). “Customer Loyalty: Toward an Integrated Conceptual Framework,” Journal of Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. 22, No. 2, pp.99-113.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Dimitriades, Z.S. (2006). “Customer Satisfaction, Loyalty and Commitment in Service Organizations: Some Evidence from Greece,” Management Research News, Vol. 29, No. 12, pp.782-800.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Dimitriadis, S. (2010). “Testing Perceived Relational Benefits as Satisfaction and Behavioral Outcomes Drivers,” International Journal of Bank Marketing, Vol. 28, No. 4, pp.297-313.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Doney, P.M. & Cannon, J.P. (1997). “An examination of the Nature of Trust in Buyer-Seller Relationships,” Journal of Marketing, Vol. 61, No. 2, pp.35-51.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Dwyer, R.F., Schurr, P.H. & Oh, S. (1987). “Developing Buyer-Seller Relationships,” Journal of Marketing, Vol. 51, April, pp.11-25.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Finney, T.G. & Finney, R.Z. (2010). “Are Students Their Universities’ Customers? An Exploratory Study,” Education and Training, Vol. 52, No. 4, pp.276-291.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Fullerton, G. (2005). “The Impact of Brand Commitment on Loyalty to Retail Service Brands,” Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences, Vol. 22, No. 2, pp.97-110.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Fullerton, G. (2003). “When Does Commitment Lead to Loyalty ?,” Journal of Service Research, Vol. 5, No. 4, pp.333-344.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Gambetta, D. (1988). “Can we Trust Trust?,” Trust: Making and Breaking Cooperative Relations, Prentice Hall, New Jersey.

Ganesan, S. (1994). “Determinants of Long-Term Orientation in Buyer-Seller Relationships,” Journal of Marketing, Vol.58, April, pp.1-19.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Geyskens, I., Steenkamp, J., Scheer, L. & Kumar, N. (1996). “The Effects of Trust and Interdependence on Relationship Commitment: A Transatlantic Study,” International Journal of Research in Marketing, Vol. 13, No. 4, pp.303-317.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Gremler, D.D. & Brown, S.W. (1996). “Service Quality: Its Nature, Importance, and Implications,” Advancing Service Quality – A Global Perspective, New York: ISQA, pp.171-180.

Gronroos, C. (1994). “From Marketing Mix to Relationship Marketing: toward a Paradigm Shift in Marketing,” Management Decision, Vol. 32, No. 2, pp.4-20.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Gronroos, C. (1990). “Relationship Approach to the Marketing Function in Service Contexts: The Marketing and Organizational Behavior Interface,” Journal of Business Research, Vol. 20, No. 1, pp.3-12.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Gruen, T., Summers, J. & Acito, F. (2000). “Relationship Marketing Activities, Commitment and Membership Behaviors in Professional Associations,” Journal of Marketing, Vol. 64, No. 3, pp.34-49.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Gwinner, K.P., Gremler, D.D. & Bitner, M.J., (1998). “Relational Benefits in Services Industries: The Customer’s Perspective,” Journal of Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. 26, pp.101-114.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Hair, J.F., Anderson, R.E., Tatham, R.L. & Black, W.C. (1998). Multivariate Data Analysis, New Jersey: Prentice Hall Inc.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Hart, C.W. & Johnson, M.D. (1999). “Growing the Trust Relationship,” Marketing Management, Vol. 8, No. 1, pp.8-21.

Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Helgesen, O. & Nesset, E. (2007). “What Account for Student’s Loyalty? Some Field Study Evidence,” International Journal of Educational Management, Vol. 21, No. 2, pp.126-143.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Hennig-Thurau, T., Gwinner, K.P. & Gremler, D.D. (2002). “Understand Relationship Marketing Outcomes: An Integration of Relational Benefits and Relationship Quality,” Journal of Services Research, Vol. 4, No. 3, pp.230-247.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Hennig-Thurau, T., Langer, M.F. & Hansen, U. (2001). “Modeling and Managing Student Loyalty,” Journal of Services Research, Vol. 3, No. 4, pp.331-344.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Hennig-Thurau, T. & Klee, A. (1997). “The Impact of Customer Satisfaction and Relationship Quality on Customer Retention: a Critical Reassessment and Model Development,” Psychology & Marketing, Vol. 14, No. 8, pp.737-765.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Holdford, D. & White, S. (1997). “Testing Commitment-Trust Theory in Relationships between Pharmacy Schools and Students,” American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, Vol. 61, Fall, pp.249-256.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Jackson, B.B. (1985). “Build Customer Relationships that Last,” Harvard Business Review, Nov/Dec.

Google Scholar

Kassim, N.M. & Abdulla, A.K.M.A. (2006). “The Influence of Attraction on Internet Banking: an Extension to the Trust-Relationship Commitment Model,” International Journal of Bank Marketing, Vol. 24, No. 6, pp.424-442.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Koerner, M.M. (2000). “The Conceptual Domain of Service Quality for Inpatient Nursing Services,” Journal of Business Research, Vol. 48, pp.267-283.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Lehtinen ,U. (1996). “Our Present State of Ignorance In Relationship Marketing,” Asia-Australia Marketing Journal, Vol. 4, No. 1, pp.43-51.

Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Levin, D.Z. (2004). “Perceived Trustworthiness of Knowledge Sources: The Moderating Impact of Relationship Length,” Journal of Applied Psychology.

Liang, C.J. & Wang, W. H. (2007). “An Insight into the Impact of a Retailer’s Relationship Efforts on Customers’ Attitudes and Behavioral Intentions,” International Journal of Bank Marketing, Vol. 25, No. 5, pp.336-366.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Macintosh, G. & Lockshin, L.S. (1997). “Retail Relationships and Store Loyalty: a Multi-Level Perspective,” International Journal of Research in Marketing, Vol. 14, No. 5, pp.487-497.

Publisher – Google Scholar

MacMillan, K., Money, K., Money Arthur & Downing, S. (2005). “Relationship Marketing in the Not-For-Profit Sector: an Extension and Application of the Commitment-Trust Theory,” Journal of Business Research, Vol. 58, pp.806-818.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Marzo-Navarro, M., Pedraja-Iglesias, M. & Rivera-Torres, M.P. (2005). “Measuring Customer Satisfaction in Summer Courses,” Quality Assurance in Education, Vol. 13, No. 1, pp.53-65.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Mattila, A. (2004). “The Impact of Service Failures on Customer Loyalty: The Moderating Role of Affective Commitment,” International Journal of Service Industry Management, Vol. 15, No. 2, pp.134-149.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Molina, A., Martin-Consuegra, D. & Esteban, A. (2007). “Relational Benefits and Customer Satisfaction in Retail Banking,” International Journal of Bank Marketing, Vol. 25, No. 4, pp.253-271.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Monteverde, K. (1995). “Technical Dialog as an Incentive for Vertical Integration in the Semiconductor Industry,” Management Science, Vol. 41, No. 10, pp.1624-1638.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Moorman, C., Zaltman, G. & Deshpande, R. (1992). “Relationships between Providers and Users of Marketing Research: the Dynamics of Trust within and between Organizations,” Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 29, No. 3, pp.314-329.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Morgan, R & Hunt, S., (1994). “The Commitment-Trust Theory of Relationship Marketing,” Journal of Marketing, Vol.58, pp.20-38.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Mukherjee, A. & Nath, P. (2007). “Role of Electronic Trust in Online Retailing: a Re-Examination of the Commitment-Trust Theory,” European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 41, No. 9/10, pp.1173-1202.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Nauman, E. & Giel, K. (1995). Customer Satisfaction Measurement and Management: Using the Voice of the Customer,Thomson Executive Press, Cincinnati, OH.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Nguyen, N. & LeBlanc, G. (2001). “Image and Reputation of Higher Education Institutions in Students ‘ Retention Decisions,” The International Journal of Educational Management, Vol. 15, No. 6, pp.303-311.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Oliver, R. (1999). “Whence Consumer Loyalty,” Journal of Marketing, Vol. 63, No. 4, pp.33-44.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

O’Reilly, C. & Chatman, J. (1986). “Organizational Commitment and Psychological Attachment: the Effects of Compliance, Identification and Internalization on Prosocial Behavior,” Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 71, No. 3, pp.492-499.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Orr, J.E. (1990). ‘Sharing Knowledge, Celebrating Identity: Community Memory in a Service Culture,’ Middleton D., and Edwards D (Ed.). Collective Remembering, Sage, London, pp.169-189.

Google Scholar

Park, C.H. & Kim, Y.G. (2003). “Identifying Key Factors Affecting Consumer Purchase Behavior in an Online Shopping Context,” International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management, Vol. 31, No. 1, pp.16-29.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Patterson, P.G. & Smith, T. (2001). “Relationship Benefits in Service Industries: A Replication in Southeast Asian Context,” Journal of Services Marketing, Vol. 15, No. 6, pp.425-443.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Patterson ,P.G., Johnson, L.W. & Spreng, R.A. (1997). “Modeling the Determinants of Customer Satisfaction for Business-To-Business Professional Services,” Journal of Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. 25, No. 1, pp.4-17.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Porter, M.E. (1980). Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors, Free Press, New York, NY.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Quester, P.G. & Romaniuk, S. (1997). “Service Quality in the Australian Advertising Industry: A Methodology Study,” Journal of Services Marketing, Vol. 11, No. 3, pp.180-192.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Ravald, A. & Gronroos, C. (1996). “The Value Concept and Relationship Marketing,” European Journal of Marketing, Vol.30, No. 2, pp.19-30.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Reichheld, F.F. (1996). The Loyalty Effect, Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Rotter, J.B. (1967). “A New Scale for the Measurement of Trust,” Journal of Personality, Vol. 35, pp.651-655.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Rowley, J. (2003). “Retention: Rhetoric or Realistic Agendas for the Future of Higher Education,” The International Journal of Educational Management, Vol. 17, No. 6, pp.248-253.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Schein, F., (1990). “Organizational Culture,” American Psychologist, Vol. 45, No. 2, pp.109-119.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Scholl, R.W. (1981). “Differentiating Organizational Commitment from Expectancy as a Motivating Force,” The Academy of Management Review, Vol. 6, No. 4, pp.589-599.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Schurr, P.H. & Ozanne, J.L. (1985). “Influences on Exchange Processes: Buyers ‘ Toughness,” Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 11, pp.939-953.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Sharma, N. & Patterson, P.G. (2000). “Switching Costs, Alternative Attractiveness and Experience as Moderators of Relationship Commitment in Professional, Consumer Services,” International Journal of Service Industry Management, Vol. 11, No. 5, pp.470-490.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Tsai, W. & Ghoshal, S. (1998). “Social Capital and Value Creation: the Role of Intrafirm Networks,” Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 41, No. 4, pp.464-476.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Vasudevan, H., Gaur, S.S. & Shinde, R.K. (2006). “Relational Switching Costs, Satisfaction and Commitment: a Study in the Indian Manufacturing Context,” Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, Vol. 18, No. 4, pp.342-353.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Venetis, K.A. & Ghauri, P.N. (2004). “Service Quality and Customer Retention: Building Long-Term Relationships,” European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 38, No. 11 and 12, pp.1577-1598.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Verhoef P.C., Franses, P.H. & Oekstra, J.C. (2002). “The Effect of Relational Constructs on Customer Referrals and Number of Services Purchased from a Multiservice Provider: Does Age of Relationship Matter?,” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. 30, No. 3, pp.202-216.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Wathne, K.H., Biong, H. &Heide, J.B. (2001). “Choice of Supplier in Embedded Markets: Relationship and Marketing Program Effects,” Journal of Marketing, Vol. 65, No. 2, pp.54-66.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Wetzels, M., de Ruyter, K. & Brigelen, M.V. (1998). “Marketing Service Relationships: the Role of Commitment,” Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, Vol. 13, No. 4 & 5, pp.406-423.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

White, L. & Yanamandram, V. (2007). “A Model of Customer Retention of Dissatisfied Business Services Customers,” Managing Service Quality, Vol. 17, No. 3, pp.298-316.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Wong, A. & Sohal, A. (2002). “An Examination of the Relationship between Trust, Commitment and Relationship Quality,” International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, Vol. 30, No. 1, pp.34-50.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Zeithaml ,V.A., Berry, L.L. & Parasuraman, A. (1996). “The Behavioral Consequences of Service Quality,” Journal of Marketing, Vol. 60, April, pp.31-46.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct