Introduction

Brief Literature Review

Education system plays an important role in promoting equality of chance, diversity and intercultural dialogue principles mostly within higher education institutions by stimulating students to be tolerant and to respect other people. This paper argues for an alternative view on cross-cultural dialogue and intercultural competence within the framework of a global knowledge-based society and economy. The global knowledge-based society implies not only moving from one place to another but also adapting and integrating people into a national and international context. Such integration and adaptation policies need specific measures in order to encourage and make the most of the intercultural contact between new-comers and locals.

The lack of specific policies for supporting intercultural dialogue may lead to acculturation. Acculturation as a concept represents a dual process of culture, psychological and behavioral changes. Berry J. (2005) states that diversity and cultural diversity in particular have a major impact on behavior, attitudes and personality of individuals in situations of intercultural contact.

Cross-cultural dialogue is not only becoming an adaptation problem but also a problem of ethics.

Ethical principles, as well as all other forms of culture, are humanly produced and culturally transmitted. By engaging in intercultural contact with different cultures, we gain a more objective view than if people only lived and promoted their own culture. The same process can work in reverse: people from other cultures may learn from our experiences and in the dialogue process different traditions and beliefs are likely to be adopted or assimilated.

Evanoff pleads for a synergetic view of a “third cultures”, which integrates the positive aspects of each of the original cultures in novel ways. “If ethical norms are cultural creations, then they can also be revised in response both to newly emerging problems and to new perspectives gained through cross-cultural contact” (Evanoff, R., 2006, page 427). Cross-cultural contacts and interactions offer the framework for new contexts of dialogue in which the norms that will govern interactions do not yet exist and hence must be created. Bouville M. (2008) considers that diversity and intercultural dialogue are also problems of ethics in the context of respecting equality of opportunities (Pless, N. M., Maak, T., 2004) consider that diversity is a cultural problem and therefore a matter of norms, values and expectations.

Bennett’s (1993) developmental model of intercultural sensitivity had identified six stages that individuals typically go through in the process of acquiring an integrated perspective. The ethnocentric stage assumes that differences are not recognized (denial), or differences are perceived but individuals believe that one culture is superior to another (defense), or differences are neglected or minimized (minimization). Within the ethno relative stage differences are recognized in a relativist way (acceptance), or differences are slightly becoming adopted (adoption), or individuals plead for bicultural perspective which use multiple frames of reference (integration). Individuals acquire a bicultural perspective by integrating some of the ideas and values of the other culture into their own way of thinking. Diversity and intercultural management becomes more important for almost all multinational and national organizations. In today’s world a lot of important companies had introduced specific policies for managing diversity. Diversity management should be viewed as an investment rather than a cost; therefore it is aimed to satisfy both economic and social goals.

Intercultural competences and intercultural dialogue request also an international co-operation in education. Within a multicultural learning environment the dissemination of the results of an international co-operation in education can be done by following the “3Ps” of knowledge dissemination as suggested by Holsapple (2003, p.112): Pull, Push, Point.

- Pull refers to individuals going to a knowledge repository and requesting explicit information.

- Push, refers to information being sent to one or more individuals as it becomes available e.g. via intranets.

- Point, refers to receiving instructions on where to find knowledge.

We suggest also the inclusion of an additional “P” for “Person”, being the individual expert who possess the respective knowledge and can provide further help. By applying these principles, mostly by using ITC tools we believe that it might be possible to strength co-operations and dialogues between cultures that traditionally experience mostly barriers in communication.

The European expansion to Asia was driven by the desire for spices and Asian luxury products. Its results, however, exceeded the mere exchange of commodities and precious metals. The meeting of Asia and Europe signaled not only the beginnings of a global market but also a change in lifestyle that influences our lives even today.

Long-distance trade played a major role in the cultural, religious, and artistic exchanges that took place between the major centers of civilization in Europe and Asia during antiquity.

We believe that a strengthening of Europe-Asia relationships is today an urgent priority. It can be initiated by the public system but it needs to be implemented by a dynamic and committed European and Asian civil society’. The objectives specified in the document “Towards a New Asia Strategy” which was approved by the European Council at Essen in December 1994 and by the European Parliament in the Summer of 1995, are to raise the EU’s profile in Asia and enhance mutual understanding and, more importantly, to strengthen the EU’s economic presence in the region.

If we want to increase business, political, and educational contacts, and if we want to support this process with the idea of cultural rapprochement and at the same time keep costs down, its seems that we have to do it in an integrated, coherent way. This means that the European countries should work together in a joint, long-term policy. One of the main constituents of this policy should be the setting up in all Asian countries of one or more fully fledged European centers where, business, academic, and cultural representatives actively promote European interests. These should be manned by European Asia specialists/researchers in all kinds of fields. They should act as intermediaries and facilitators for business, arts, and academic contacts. The Asian countries should be invited to establish similar centers in Europe. Fully fledged integrated centers in Asia should also function as initiators of all types of activities, as clearinghouses for massive fellowships programmes for Asian students, managers, researchers and artists in Europe; as consultants for European and Asian companies who could initiate new business, academic and cultural contacts. We consider that regarding the strengthening of mutual understanding between Europe and Asia, one obstacle standing in the way of enhanced understanding is the tendency to deal with Asia as a cultural entity. This has often prevented Europe from understanding the special characteristics of the three major sub-regions (South, East, and Southeast Asia) not to speak of those of individual countries and areas.

Nowadays the tremendous developments in Asian countries demand from Europe a thorough knowledge of the differences and the idiosyncrasies of each country, state, or area. Taking into account the dynamics and diversity in Asia, we consider that each of the European countries have to be actively engage in its own individual relationships with Asian countries and each academic institute or business company have to initiate its own individual contacts with counterparts in Asian countries. Furthermore, high priority should be given to the youth of both regions. In order to ensure optimal benefit and maximum coherence in the long term, exchanges of large groups of qualified young persons in all fields must be considered to be of crucial importance. In order to assist the adjustment of cultural perceptions and policy approaches to the new global knowledge-based society conditions, high level meetings and senior exchange programs have already been set into motion. Other measures could be: the organization of region-wide, pre-university level exchange programs; training and mobility programs specially dedicated to the university level; virtual and real-life networking and alumni associations. Under these circumstances we consider that in education and in most scientific fields international collaboration is unavoidable. This can be envisaged as pooling resources and create sufficient critical mass to make a meaningful contribution, sometimes as sharing unique historical collections or special laboratory facilities, and developing complementary research and educational capacities. For each of these purposes, there is huge scope for increased collaboration between European countries and between Europe and Asia mostly by:

- Establishing large, integrated centers in the most important cities both in Europe and Asia. The planned ASEM Asia-Europe Foundation to be set up in Singapore with contributions from Asian and European countries for the promotion of think-tanks, peoples, and cultural groups is a good, although modest and belated start;

- Mounting of an extensive exchange programme for young specialists in all fields (from universities as well as from vocational institutions; from companies and non-governmental organizations);

- Restructuring of the individual, national educational systems into an European system such as the European Higher Education and the European Research Areas;

- The introduction of a curriculum which provides access to non-Western values, concepts, and ideas.

The Asia Committee of the European Science Foundation (in Strasbourg) is willing and capable to function as an intermediary and catalyst in these activities. We strongly believe that if we want Europe to be an equal partner in global matters in the twenty-first century we should actualize a strong Asian presence in Europe and secure Europe’s presence in Asia. The EU’s communication on its New Asia Strategy and likewise its recent communication on the Asia-Europemeeting in Bangkok, the so called ‘ASEM‘, are stated again almost completely in terms of business interests.

Within the ten lines only devoted to non-mercantile issues in the EU Communication on ASEM, the idea of building bridges between civil societies is described as: ‘a major challenge in our drive to overcome existing gaps in communication, understanding and cultural dialogue.

A strengthened mutual awareness of European and Asian cultural perspectives will be a key supporting element in strengthening our two-way political and economic linkages’ (The Asia Committee of the European Science Foundation, 2010). The recent “Chairman’s Statement” on the Asia-Europe meeting in Bangkok pays some specific attention to the cultural line. We consider that the underlying motivations behind the EU’s recently enhanced interest in Asia stem from an unambiguous combination of anxiety and greed. Anxiety born of the fact that in the next century Asia will account for more than half of the world population and might become the world’s most powerful region in an economic, and possibly also in a political, respect. Cultural dimensions can be helpful.

The political and / or the business relations seem to create a more appropriate context for the higher education environment mostly in the context of globalization, given the fact that the access to education has became more and more an international issue.

According to Hofstede and Hofstede (2005, 371) cross-cultural studies bring about a paradigm shift (Kuhn 1970) in how we understand people behavior at a national, international and global level. In contrast to much descriptive research into differences between cultures (e.g. Hofstede and Hofstede 2005; Schwartz 1992), little material is published dealing with the context of multicultural learning environments. Hofstede’s (2005) five cultural dimensions are: Power Distance (PDI); Individuality (IDV); Masculinity (MAS); Uncertainty Avoidance (UAI); Long or Short term Orientation (LTO).

- Power Distance relates to the emotional distance between people. A high Power Distance (PDI) would indicate a strong sense of hierarchy and acceptance of one’s role within it, while a culture with low PDI would tend to regard others as equal, worthy of consultation and assuming little success in playing on the power one might have over the other.

- Individuality versus Collectivism (IDV) relates to the ties individuals have within their society. They are loose in individualist societies and stronger in collectivist societies, and expressed by a reliance on group norms and conformity to visible, behavioral standards in the latter.

- Masculinity versus Femininity (MAS) relates to role patterns between genders. A society would be consideredfeminine if the roles between the genders were not clearly distinct and in which modesty, tenderness and quality-of-life issues would characterize the approach to life and society.

- Uncertainty Avoidance (UAI) describes the level of ambiguity a society is prepared to live in. A society would be high on this scale if they relied on written rules, clear statements and discernable patterns but feel uncomfortable if such patterns are not obvious.

- Long-Term Orientation (LTO) denotes attitudes on the importance of past, present and future. A short-term orientation relates to the present and past, while the opposite orientation cares particularly for the future. For the former, Hofstede (2005, 210) cites such virtues as respect for tradition, preservation of face and fulfilling obligations.

Using the cultural dimensions Hofstede pointed out that common sense takes a precedence over rationality for the Asian. “Rationality is abstract, logical, analytical whereas the spirit of common sense is more human and in closer contact with reality” (Hofstede, 20005, p. 230). Usability is mostly influenced by the Western culture that strongly retains the value ofrationality. Instead the Asian culture focus on values such as virtue.

Asia in the Eyes of Europe and Romania

„Asia in the Eyes of Europe” project offers an opportunity for Asia and Europe to look for their understanding of one another, through examining European public, media and opinion leader’s attitudes, knowledge and perceptions of Asia (http://www.irsea.ro/Asia-in-the-Eyes-of-Europe-research-project/). The project has evolved from the ongoing initiative, „The EU through the Eyes of Asia”, which has carried out research looking at the perceptions of the EU in Asia across 12 research locations since 2005. The „Asia in the Eyes of Europe” research project provides comparability to the findings of the „EU through the Eyes of Asia”.

The project was aimed to improve the understanding of Asia in Europe and to create a platform to enable civil society, business, researchers, teachers, students, policy makers, media and a broad range of stakeholders to understand one another better. The two year research project was carried out with a multi-level and multi-faceted methodology designed to carry out a representative sample of eight EU countries. It had examined the perceptions of Asia in Europe in three distinct arenas:

- Public Opinion: The public opinion survey has been carried out in June and July 2010 across eight EU countries with varying samples of 2000 or 1000 respondents depending on the size of population. Countries included were: Austria (1000), Belgium (2000), Denmark (1000) France (2000), Germany (2000), Italy (2000), Romania (1000), United Kingdom (2000). The public opinion survey was carried out in collaboration with the „European Identity” project by the London School of Economics.

- Media Analysis: The Media analysis was trying to gauge the representations of Asia in European media over a period of three months from September to November 2010. The research looked at three media outlets in each location: a national reputable newspaper with the highest readership; a national popular newspaper with the highest readership and the most popular TV news broadcast (Public Service Broadcaster if applicable). An additional aspect of the media analysis was the inclusion of a European-level media analysis tracking news from media such as Euro News and European Voice.

- Opinion Leader interviews: The interviews were seeking to access the perceptions of Asia amongst European Opinion leaders adding to the validity and the scope of the data collected. The interviewees had been drawn from four sectors, namely: business; politics; media; civil society/academia. Specially trained researchers were seeking to carry out interviews with approximately 12 interviewees in each location and with a view to interviewing Brussels-based EU opinion leaders.

The project has conducted a public opinion survey of 13,000 respondents in collaboration with an ongoing research initiative of the London School of Economics (LSE). The media research has provided daily analysis of 29 national media outlets across Europe — including BBC, Le Monde, Zeitung, Euro News and others. The last element of the research project is to collect the perceptions of Asia amongst opinion leaders from the media sector in each of the countries.

Asia in the Eyes of Romania

The Romanian Institute for Euro-Asian Studies (IRSEA) had been nominated to conduct a research in Romania during 2010 and 2011 about the local perceptions of the Asian continent. IRSEA is a researching partner for the “Asia in the Eyes of Europe” research project developed by Asia Europe Foundation (ASEF) with the financial support of the European Commission. Through its studies and research activities, IRSEA contributes to better understanding and cooperation between people in Europe and Asia, cultivating and promoting Asian cultural values in European countries and European values in Asia. By its studies IRSEA intends to contribute to:

- The consolidation of the mutual understanding, deeper engagement and cooperation between peoples of Europe and Asia;

- The promotion of Asian cultural values in Europe and those of Europe in Asia;

- The affirmation of democratic and ethical principles and free movement of ideas in Arts, Science, Economy, Education and Politics in the two regions.

IRSEA is collaborating with students, graduate students (PhD or Masters) in conducting research projects and its academic activities. Among the metaphors presented in Romania most have a positive statistical significance: the writers use metaphors most of the time in an admiration fashion regarding the Asian people. Asia (especially the Asian economy and culture) appears to be quite a force: (“the Asian kitchen has conquered us”, “Asian products have invaded the IT&C market” etc.). Total of 133 pieces of news, with the majority (75%) of articles originating in Adevarul, followed by Libertatea (17%) and TVR News (7%). Most of the articles have been written by local correspondents, with only minor percentages written by foreign correspondents. There have been instances of articles being translated from foreign newspapers. There have been significant differences between the framing categories of different outlets: while Adevarultreated “Economy”, “Politics” and “Social Affairs” almost equally, Libertatea focused mainly on “Social Affairs”, and theTVR News on “Politics”. The keywords have been evaluated as neutral in the majority (>70%) of the articles, regardless of the news source. Adevarul leaned in the direction of a positive evaluation of Asia (22% positive versus 7% negative).Most of the mentions had been minor (a trend that was present regardless of the medium: 88% in Adevarul; 91% inLibertatea and 78% in the TVR1 – TV news), often consisting of a single key word in the whole article. The most frequently mentioned country was by far China.

There have also been frequent mentions of Japan, India and South Korea. Individual countries have been mentioned much more frequently (e.g.: in the case of China, terms such as “China”, “Chinese” etc. have been often mentioned more than 5 times per day — compared to the average of 1,5 times/day for “Asia/Asian”. Asian institutions of higher education have also been presented or advertised frequently.

We consider that education in general and higher education institutions in special have a key role for the improvement of the cooperation and dialogues between Europe and Asia and particularly for the strength of Eurasian inter university dialogues and co-operation. In order to contribute to this development we believe that intercultural education and intercultural competences have to be developed.

Intercultural Education, Intercultural Competences and Intercultural Dialogue in Higher Education

Nowadays universities need to have a specific behavior like organizations to remain competitive and to permanently upgrade their curricula to the specific requirements of the labor market. Some authors indicate that participation in intercultural education can result, mostly in the short-term, in changes to individual attitudes and cross-group relationships (Dessel, Rogge, and Garlington 2006; Rozas 2007; Vasques Scalera 1999). While there are studies (Halualani, 2008) that reflect how culturally different students define, make sense of, and experience intercultural interaction at a multicultural university in the US, they are not centered on intercultural competencies. Stier J (2006) argues that intercultural communication might be seen as an academic discipline and that the education systems have to support Education for Intercultural Communication.

In order to develop Euro Asian interuniversity dialogues and co-operation we consider that it is crucial to promote a constructive intercultural dialogue within universities for contributing to their development and performing successfully in the long-run. Universities that function within a multicultural framework should promote “cultural respect” for all persons involved in intercultural communication, regardless of their origins and cultural choices. Intercultural competence and intercultural effectiveness are crucial today. Intercultural competence can be divided into: content-competencies andprocess-competencies (Stier 2003).

- Content-competencies encompass a one-dimensional or static character and refer to knowing a specific aspect.

- Process-competencies consider the dynamic character of intercultural competence and its interaction context(Hall 1976; Stier, 2004).

The knowing how-aspect of intercultural competence engages both intrapersonal and interpersonal competencies. Intrapersonal competencies involve cognitive and emotional skills of individuals, copying with diverse feelings – xenophobia, frustration, ethnocentrism (Gudykunst 2003). Interpersonal competencies refer to interactive skills being aware of owner’s own interaction style (communication competence) and adequately responding to contextual meanings (situational sensitivity). Intercultural communication education should enhance students understanding of the dynamics of intercultural interactions. It should enable them to obtain intercultural competence. Intercultural Programme’s StudentOutcomes refer to meta-competences and extend beyond „knowing that” and „knowing how”-aspects of culture. Instead they are about „knowing why” and or even „knowing why one knows why”. The Features of Academic Curricula and Teaching Orientations (FACTO) make up a fertile ground for intercultural learning and acquisition of intercultural competences (Stier 2006).

Curricula Internalization and Culturally Affected Curricula

Within the framework of a global knowledge-based society and economy it had been developed the curriculum internationalization – the process of integrating an international, intercultural or global dimension into the purpose, functions or delivery of higher education. Curriculum internationalization needed to prepare graduates for the international labor market. Our research on curricula internalization is based on a survey comprising 135 students from the Academy of Economic Studies Bucharest (AESB) and 56 students from Politehnica University of Bucharest (PUB).

It was conducted in the first quarter of 2010. With respect to the structure of respondents we mention that: the average age is: 20 years on AESB and 23 years on PUB; respondents are fourth year students and first year students and for all of them their studies take place in English. The academic curricula in their university are designed in order to be compatible with those of similar universities in Europe. In order to ensure comparability and compatibility:

- The same or similar subjects are taught and there are applied similar teaching techniques;

- Teachers use internationally recognized books;

- There is a focus on the development of business, management, marketing, accounting, mathematics, law, political science, finance and economics skills.

According to our survey, students consider that Curricula Internationalization means:

- Standardization including however cultural differences;

- The same curricula for all countries in order to make it easier for students to go and study abroad;

- Offering more perspectives for studying abroad by teaching in foreign languages etc.

- Including international information and examples of best practices in the curricula;

- A set of common subjects and examinations tools.

Considering why such measures are not applied yet our students express their opinion according to which:

- Countries and particular experiences of universities are too much different to make them adopt the same standards;

- It is technically too difficult to make all universities change their curricula for a standardized one;

- There are too many constraints for certain subjects.

Suggestions made by our students include:

- The use of a foreign language for teaching;

- The same information should be presented, but the teaching methods should be adapted to the environment and mentalities of that country;

- Better established education standards;

Curriculum internationalization requires international standards for accreditation of universities that can provide curricula internationalization. Accreditation organizations have their own model of curricula. These models are the standards for accredited programs. Standards are universalizing and even globalizing by nature. What this paper suggests is that the curriculum reflects cultural patterns of the society in which it is offered. No matter how structured a curriculum may become in accord with accrediting bodies and established standards, cultural influence prevails. As an example, a Romanian professor of management will implicitly incorporate Romanian social constructs and culture into his/her teaching of business management, thereby, potentially altering the context of the standard. Likewise, an American professor implicitly incorporates notions of American business culture with respect to American markets in the context of an objective standard. And for sure a Chinese professor will incorporate Chinese culture and values.

Business education accreditation through international accreditation organizations such as AACSB Internationalincorporates standards for faculty, students, curriculum, institutional support and governance-all based on the American educational model. While this provides a consistent context for quality business academic programs, it does so under standardization basis without significant inclusion of cultural variation with respect to the socio-cultural backgrounds of the faculty and students. The presumption of achieving recognized quality academic programming is attained throughstandardization based on the American educational system – not through an indigenous localized educational system.

Furthermore, the inclusion of Eastern European countries such as Romania into the European Union has complicated the issue. The recent members of the European Union have been/are in process of migrating from an Eastern European socio-cultural-economic frame towards that of a more Western European model. These countries with their associated economies and business context incorporate, to a certain degree, the international “big business” context to which accreditations like AACSB International is directed.

However, these countries, like most countries of the world have a majority of business activity that is localized inpredominantly small and middle sized businesses that serve the local and regional economy. The challenge is to modify global business curricula that are currently directed to big international business standardized practice to be compatible and useful for localized regional culturally framed businesses.

Our research on Two Romanian Universities: Academy of Economic Studies Bucharest and Politehnica University of Bucharest

With the aim of understanding the implication of intercultural dialogue and intercultural capabilities in the context of equal learning opportunities among students and being able to provide an accurate interpretation of results we had performed a qualitative research in two prestigious universities in our country. We focused our research on the English section fromthe Faculty of Business Administration (FBA) that offers courses taught in foreign languages (English, French and German) and functions within the Bucharest Academy of Economic Studies(AESB). In order to discover if the subjects taught make any difference we also considered the Faculty of Engineering in Foreign Languages (FEFL), the English section, at “Politehnica” University of Bucharest (PUB).

We applied the questionnaire method for both universities on 135 students from AESB (all belonging to the FBA faculty) and 56 students from PUB (coming from Faculty of Engineering in Foreign Languages – FEFL). There is the same sample as in the case of curriculum internalization with the average age of 20 years old on AESB and corresponding 23 years old on PUB. The questionnaire was addressed to students from the first year to fourth year students.

We present briefly some of the results of our survey. The assumptions of the applied research methodology are: equality of chance is respected; intercultural education implies intercultural contact for both faculties; intercultural sensitivity & intercultural competences can be achieved for both faculties.

The primary source of data was a 28-question survey that focuses on students’ knowledge, attitudes and experiences regarding multicultural education. The questionnaire had two parts: the first part took into account the characteristics of our respondents (such as: faculty, year of study, nationality, age), while the second part was centered on the students’ opinion and perception on intercultural dialogue and intercultural competences accumulated in university. Twenty-five of these survey questions were multiple choice questions and three of them were open questions. One of the 28 questions is interpreted through the Likert scale.

The open questions: (1) provide solutions for respecting and promoting an equal opportunities climate in universities; (2) provide suggestions for universities as to how sustain intercultural dialogue and cultural diversity in a multicultural learning environment and (3) identify what kind of competences are important resources for the potential employer.Multicultural training is considered as an opportunity to stimulate students’ ability to work effectively with various cultural identities. For the Faculty of Business Administration (FBA) had participated first year business undergraduate students, mainly of Romanian nationality (94%), with foreign students’ in our survey from: Kuwait (3%), Moldavia (3%). For the Faculty of Engineering in Foreign Languages (FEFL) students were fourth year and first year undergraduates, mainly of Romanian nationality (70.9%), with foreign students’ in our survey from: Nigeria (8.33%), France (12.5%), Iran (4.16%); Cameroon (4.16%)

The survey was asking if students had interactions with students of other nationalities and citizenships than Romanian. All respondents confirmed that they had interaction with foreign students. Thus, 42% said that they interacted with a number of 1 to 10 foreign students; 26% interacted with 11 to 20 foreign students; 22% with more than 30 and 10% with 21 to 30 foreign students. The interactions have been with various nationalities such as Nigerian, Spanish, Pakistanis, Taiwanese, French, German, American, Russian, Dutch, Turkish, Greeks, Portuguese, Austrian, Italian, Arabs, Egyptian, Iranian etc. The circumstances under which the FBA students declared that they interacted with foreign students were university activities. For the FBA students university activities represent a large proportion – 57%, while 5% is on job experience and 38% personal experience.

Regarding the engineering students, 39% declared that they interacted with foreign students in university activities, while 34% indicated personal experience and 26% job experience.

The circumstances presented offer a broader range of information regarding their experience, their openness to intercultural dialogue, their interaction preferences and their native inclination to be open to such intercultural communication through different experiences.

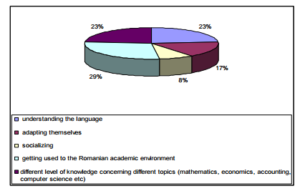

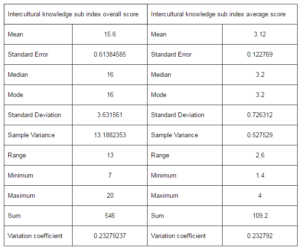

When asked to identify the main difficulties that foreign students faced within the educational environment, the answers were: “understanding the language” (18% FBA and 33% FEFL); “adapting” (18% FBA and 13% for FEFL); “socializing”(10% FBA and 4% FEFL) “getting used to the Romanian academic environment” (31% FBA and 26% FEFL) and “different level of knowledge concerning different topics” (23% FBA and 24% FEFL). Figure 1presents the results for the hall survey on both universities.

Figure 1.Difficulties Experienced by Foreign Students in Our Education System.

Around 60% of students from both universities agreed on the fact that the equal opportunities climate is not affected; the other 40% considered that equality climate is affected mainly by students’ difficulties. Although this percentage is lower than 60%, it shows that there is still much to do in order to ensure equality climate in both universities. When asked how these difficulties perturb equality climate students exemplified: different competencies achieved; not all the materials are in English; different levels of knowledge so different chances; there might be conferences or workshops in Romanian which they do not understand. Different countries request different skills and levels of knowledge. It seems that sometimes it is quite hard to adapt to team work; their results at school are influenced by their emotional well-being which in turn is influenced by the problems of socializing and understanding the language.

When asked to provide solutions, students suggested: socializing programs; extra learning classes for foreign students; mandatory lessons of Romanian; being part of a team; guiding councils. Asked which are the policies or measures taken by universities or faculties to help improve or solve such difficulties the responses were: 36% from FBA and 29% from FEFL felt that “special preparation programs are necessary”; 28% from FBA and 36% from FEFL identified as solution “promoting courses to boost intercultural dialogue and intercultural competence and sensitivity focusing on the cultural specificity of each student”, 21% FBA and 16% FEFL chose “disseminating materials with useful information” 20% form FBA and 14% FEFL thought that “organizing workshops” will be the solution. For the question “How much does your university/faculty focus on supporting management of diversity and equal opportunities?” the answers were: “a lot” (14% FBA, 4% FEFL), “to some extent” (46% FBA and 22% FEFL), “have no knowledge of it” (26% FBA, 39% FEFL), and “not enough” (14% FBA and 35% FEFL). Asked to identify in which situation students consider that they are equally treated, most of respondents chose exams (FBA 27%, FEFL 23%) and teaching methods (FBA 27%, FEFL 25%). There were also other available responses such as: university support; teacher attitude at seminars or laboratories and university facilities (accommodations, cafeteria, libraries etc).

The answers reflect a certain degree of inequality. We should mention that foreign students identified unequal treatment most of all with respect to the university support (FBA 13%, FEFL 20%) and university facilities (FBA 14%, FEFL 14%).

Asked about their opinion on intercultural collaboration in homework and projects students consider that: “each of them have to learn from others” (63%FBA, 52% FEFL), “they will do all their best so that foreign colleagues feel integrated” (37% FBA, 33% FEFL), “they will have to work harder to cover for the foreign colleague’s part” (0%FBA, 15%FEFL), or “they do not enjoy working in multicultural teams” (0% FBA, 0% FEFL).

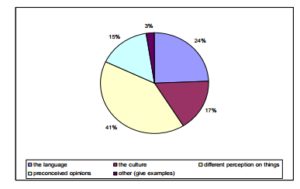

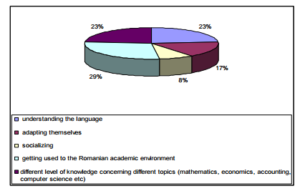

Respondents added communication difficulties encountered in the relationship with foreign students, 20% FBA and 31% FEFL identified the “language”, 45% FBA and 34% FEFL identified “different perception on things”, 15% FBA and 16% FEFL identified “prejudice”, 20% FBA and 13% FEFL identified the “culture”. Complete results are presented in the figure 2.

Figure 2. Communication Difficulties Encountered in the Relationship with Students of Other Nationalities & Citizenship

Asked about the importance of studying all the subjects in a foreign language for intercultural communication students rated the following: “university studies in a foreign language help us socialize more easily” (28%FBA, 28% FEFL), “we are much more open to communication” (26% FBA, 21% FEFL), “we feel better prepared to face any future challenges related to intercultural dialogue” (35% FBA, 33% FEFL), “university studies in a foreign language help us only to improve our language skill” (11% FBA, 16% FEFL).

The next question reflects the importance of certain components of intercultural competence. Students were asked to rate from 1 to 4 (where “1” represents least important and “4” most important) the following components of intercultural competence: cultural empathy; cross-cultural awareness; flexibility; foreign language; adaptability to intercultural environments; respect for other cultures; interpersonal skills; cross-cultural communication skills; cooperation between people from other cultures; appropriate and effective behavior. A complexity index will be presented bellow based on the analysis of this item. The highest score was achieved by “respect for other cultures” (34 times rated “4”), followed by foreign language (29 times rated “4”) and flexibility (22 times rated “4”). The “2”, “3” and “4” categories were considered positive attitudes towards intercultural competencies, 93% of respondents rated components using these three values.

When asked about the possible positive impact of studying in a foreign language on students’ future career, respondents from both faculties consider in a proportion of 94% FBA and 96% FEFL that their future career will be positively influenced by studying all subjects in a foreign language. The importance of studies in a foreign language for intercultural communication in the university was assessed as follows: 30% FBA and 32% FEFL identified “better communication skills adapted to global markets and to intercultural environment”; 27% FBA and 28% FEFL identified “better skills in the field of study due to the international content of the academic curricula”; 17% FBA and 23% FEFL chose “high level of knowledge and skills acquired due to international content of the academic curricula”; 15% FBA and 12% FEFL felt that “professors’ international experience will be translated into better knowledge and skills”; 11% FBA and 5% FEFL considered that “professors’ international experience will be translated into better teaching methods”.

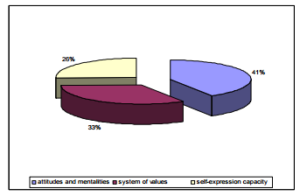

Around 83% of the students in FBA and 92% of the students in FEFL said they identified differences in attitude, mentality and behavior at students of other nationalities.

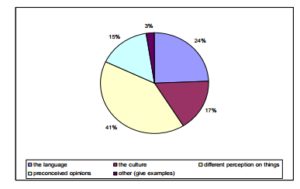

Those having identified differences said that these differences consisted in “attitude and mentality” (45% for FBA and 36% for FEFL), “system of values” (33% for FBA and 32 % for FEFL) and “self-expression capacity” (22% for FBA and 32% for FEFL). According to the respondents’ opinion, working and studying in a culturally diverse environment favorable to intercultural dialogue can lead to: “more opportunities to manifest in a creative way” (30% for FBA and 32% for FEFL); “use of the innovation and creativity potential in a more operational way” (28% for FBA and 36% FEFL); “resourceful work outcomes, including career and personal development” (42% for FBA and 32% FEFL).

Figure 3. Differences in Attitudes, Mentality and Behavior at Students of Other Nationality/Citizenship than Romanian

The percentage of the Asian students is quite low in the structure of our sample. So we could not focus yet on the Euro Asian intercultural dialogues. But as teachers interacting both with European and Asian students we consider that for our future research it will be quite interesting to focus on this dimension.

When we work on projects based on team and trust building we try to mix the structure of the team and always the Asian students made the difference in a quite significant way. European students and mostly Romanian students like to integrate the Asian students within teams.

Our survey offers a multidimensional perspective over the knowledge, attitude and experiences regarding multicultural education.

Convinced about the complexity of our research topic we tried also to develop a complexity index of intercultural competences that might be useful for future development of this kind of research.

The Complexity Index of Intercultural Competences

As mentioned previously, J. Stier’s work revealed both the content-competencies (that refer to knowing the history, language, custom, symbols and taboos) and the process-competencies (related to intercultural competences that are much more dynamic and quite difficult to be identified).

Starting from this point of view we divided the components of intercultural competences into categories: intercultural sensitivity and intercultural knowledge. For the first category it was assigned a sub index of Intercultural Sensitivity (IS). IS takes into account: cultural empathy; cross-cultural awareness; adaptability within intercultural environment; respect for other cultures and flexibility.

For the second category it was assigned a sub index of intercultural knowledge (KI). KI takes into account: foreign language; cooperation between people from different cultures; cross cultural communication skills; interpersonal skills: appropriate and effective behavior.

We tried to investigate if one of the two sub indexes is rated as much more important than the other. Respondents were asked to rate the IS and KI components on a Likert scale from “0” until “4”. This methodology is aimed to determine a complexity index of intercultural competences. The correlation between the two sub indexes and the complexity index(CIn) of intercultural competences can be defined based on the following relation

CIn = IS + KI

Hypothesis:

- Intercultural sensitivity sub index (IS) and intercultural knowledge sub index have equal weights in the overall complexity index of intercultural competence.

- It takes both sensitivity and knowledge on intercultural dialogue to prepare and value intercultural interactions.

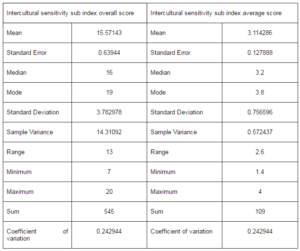

For the IS sub index we calculated the overall score and an average score that helped us to compare these values with the values of the Likert scale. The overall score of the sub index is calculated by summing the individual scores from each respondent and the overall value is divided by number of respondents. For the average score we divided the overall score of the sub index with the number of the components of the intercultural sensitivity on a scale of 5. For the sample from Politehnica University of Bucharest the IS sub index the overall score is 15.57 and the average score is 3.11.

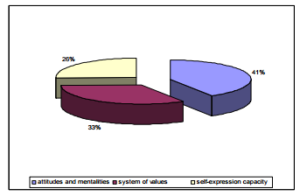

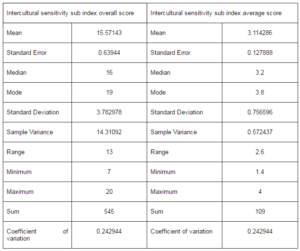

These results show that most students consider that all the components of the intercultural sensitivity are appreciated as important. Next we calculated for the intercultural sensitivity sub index the median, mode, mean, standard deviation and the coefficient of variation. The results are presented in table 1.

Table 1. Indicators for the Intercultural Sensitivity Sub Index, Overall Score and Average Score

The value of the coefficient of variation is less than 0.35, meaning that the series is relatively homogeneous and that the central tendency indicators are quite representative. For the IS sub index, adaptability within intercultural environment has the highest weight and the highest sore, followed by flexibility and cross cultural awareness.

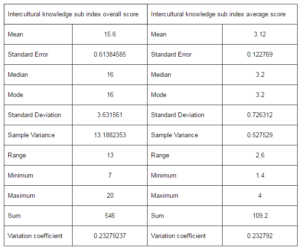

For the KI sub index (that included: cooperation between people from different cultures; foreign language; cross-cultural communication skills; interpersonal skills; appropriate and effective behavior) the overall score is 15.6 and the average score is 3.12. This average score shows that most students consider that intercultural knowledge is important.

For the intercultural knowledge sub index we had also calculated median, mode, mean, standard deviation and the coefficient of variation. Results are presented in table 2.

Tabel 2. Indicators for Intercultural Knowledge Sub Index, Overall Score and Average Score

The value of the coefficient of variation is again less than 0.35, meaning that the series is relatively homogeneous and the central tendency indicators are quite representative.

In the KI sub index, foreign language has the highest weight and the highest sore, followed by cooperation between people from different cultures.

The complexity index of the intercultural competences shows that it takes both components (knowledge and sensitivity) to interact and meet the optimum environments such as to convert resources and intercultural diversity into key sources for a sustainable competitive advantage. The next question was dedicated to identify the importance of specific aspects of equal opportunities and diversity within an institutional and organizational context. There had been provided seven possible benefits of equality of opportunity and diversity. Respondents were asked next to assess them on a scale starting from unimportant and evolving to very important. We were interested to identify among the analyzed variables, which were rated as being considered to be more important. The possible benefits were: promoting a positive work environment driven by innovation; promoting diversity and mutual respect; flexibility and ability to adapt quickly in solving the problems faced; better management of differences between people; the decrease in the perception of discrimination; implementing an organizational culture of diversity; stimulating creativity. Students considered that promoting a positive work environment driven by innovation should be the most important benefit of applying the principles of equal opportunities and diversity (96%), followed by promoting diversity and mutual respect (95%), flexibility and ability to adapt quickly in solving the problems faced (92%). At the end of the questionnaire students were invited to provide some recommendations in relation to ensuring equal opportunities, diversity and intercultural dialogue within the university. Among the most frequent recommendations provided by students we mention:

- Faculty management staff should ensure adequate conditions to implement the principles of equal opportunities for all students.

- Universities would provide special programs to support equal opportunities and they will also establish a multicultural and multiethnic program, where all students and teachers should be involved, providing the possibility of interactions among people belonging to different ethnicities and nationalities.

- Organizing special events such as a special day for each minority group where every ethic/national group can come up with specific habits, traditions, food.

- Encourage multicultural teamwork within projects and seminar activities.

- Promote a favorable environment that might contribute to both professional and personal development of each student with a strong focus on creativity.

Based on the analysis of qualitative data collected within the survey we can draw the following main ideas:

- By investigating intercultural sensitivity and intercultural competences considered within a complexity index we found that respondents appreciate that we have to take both components into consideration in order to value intercultural dialogue. Intercultural sensitivity sub index value was smaller than intercultural knowledge sub index.

- In Romania research dedicated to intercultural dialogue are on the beginning. The majority of respondents appreciated the initiative of our research project and had welcomed it; they also provided and offered suggestions and recommendations for improvement.

Conclusions

We consider that Romanian universities have to think more of becoming part of an international networking by being actively involved within some international co-operation educational Programmes mostly on the Master and PhD level. These Programmes could be specially designed for the use of the co-operation members. This approach should enable all the members to have easy access to all types of searchable documents (e.g. co-operation publications – existing and/or newly and commonly developed – relevant texts, emails, and web pages, interesting scanned documents, news and developments of the co-operation.

An informal discussion room (even a virtual one) as a knowledge creation area should be available where constantly sessions of joint work, understanding/explanations of procedures, questions and answers, discussions of interesting topics, experimenting and sharing of feelings can flow freely. This knowledge creation area is regarded as an arena to share tacit knowledge.

While business education currently prides itself in its attempt to incorporate global perspectives, business curricula can be argued to be, in reality, at a local level. “We have to think globally, but act locally” This is, in part, due to standardization attempts driven by accreditation that provides a homogenized solution in a varied and cultural driven world. The inclusion of cultural dimensions in the business education model might enrich potential for successful global application and understanding. While a case can be made for successful business practice and the teaching of such regional and national cultural implications of managerial style and governance, it must be assessed and incorporated in the business practice. For instance, the use of a US or UK management textbook in a Romanian business class does not necessarily result in Romanian managers managing in a US or UK management style. The Romanian managers will execute in a regionalized culturally impacted manner thus mutating the homogenized business model. If this in fact is the case, the cultural dimensions as argued by Hofstede and Hofstede (Hofstede and Hofstede, 2005) should be a foundational component of the global business model. The paper supports a research model of a business curriculum through the inclusion of Hofstede and Hofstede’s work. Future research has to develop a comprehensive model. Our research results suggest for both universities that students are open to support intercultural competence & sensitivity. They argued their answers mostly based on the fact that multinational companies prefer experienced employees, who are more open-minded, tolerant and open to diversity. We suggest the following measures to be taken in universities: promoting intercultural collaboration between students, especially during academic activities; assigning a person or a fellow student to guide and help foreign students; ensuring equal treatment in all university facilities; being more involved and open towards solving students’ difficulties; implementing a Code of Practice for intercultural communication and intercultural sensitivity.

Acknowledgment

The paper disseminates a part of the results obtained within the national research project “Parteneriate/Partnership 92116”.

References

Bennett, M. (1993). ‘Towards Ethnorelativism: A Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity,’ in R.M. Paige Editor Education for the intercultural experience Yarmouth Intercultural Press pp 21-71

Google Scholar

Berry, J. (2005). “Acculturation: Living Successfully in Two Cultures,” International Journal of Intercultural Relations, vol 29, pp 697-712

Publisher – Google Scholar

Bouville, M. (2008). “Is Diversity Good? Six Possible Conceptions of Diversity and six Possible Answers,” Science and Engineering Ethics, Vol 14, Issue 1 pp 51-63

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Burčik, V., Kohun, F. G. & Skovira, R. J. (2007). “Analyzing the Effect of Culture on Curricular Content: A Research Conception,” Issues in Informing Science and Information Technology Volume 4

Publisher – Google Scholar

Dessel, A., Rogge, M. E. & Garlington, S. B. (2006). “Using Intergroup Dialogue to Promote Social Justice and Change,”Social Work Journal, Vol 51, no. 4 pp 303—315

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Dooley, R. (2003). ‘Four Cultures, One Company: Achieving Corporate Excellence through Working Cultural Complexity,’Organization Development Journal, 21(2), pp 52-66.

Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Drucker, P. F. (1997). “The Global Economy and the Nation-State,”[Online] Foreign Affairs, vol 76, no 5.[Retrieved July 30, 2011], http://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/drucker.htm

Publisher

Evanoff, R. (2006). “Integration in Intercultural Ethics,” International Journal of Intercultural Relations, Vol 30 pp 421-437

Publisher – Google Scholar

Halualani, R. T. (2008). “How Do Multicultural University Students Define and Make Sense of Intercultural Contact? A Qualitative Study,” International Journal of Intercultural Relations, Vol 32, pp 1-16

Publisher – Google Scholar

Hofstede, G. (2001). “Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations across Nations,” Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Hofstede, G. H. & Jan Hofstede, G. (2005). “Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind,” New York: McGraw-Hill.

Publisher

Huang, L., Lu, M.- T. & Wong, B. K. (2003). ‘The Impact of Power Distance on Email Acceptance,’ Journal of Computer Information Systems, 44(1), pp 93-101.

Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Kim, D., Pan, Y. & Park, H. S. (1998). ‘High- versus Low-Context Cultures: A Comparison of Chinese, Korean, and American Cultures,’ Psychology & Marketing 35, pp 31-37

Megle, R. (2010). ‘Media Analysis,’ Romania, Romanian Institute for European-Asian Relations

Pless, N. & Maak, T. (2004). “Building an Inclusive Diversity Culture: Principles, Processes and Practice,” Journal of Business Ethics, Vol 54, pp 129—147

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Poglia, E., Mauri-Brusa, M. & Fumasoli, T. (2007). “Intercultural Dialogue in Higher Education in Europe,” University of Lugano.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Rozas, L. W. (2007). “Engaging Dialogue in Our Diverse Social Work Student Body: A Multilevel Theoretical Process Model,” Journal of Social Work Education , Vol 43, no. 1, pp 5—29.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Stening, B. W. & Hammer, M. R. (1992). “Cultural Baggage and the Adaptation of Expatriate American and Japanese Managers,” Management International Review 72(1), pp 77-89.

Publisher

Stier, J. (2004). “Intercultural Competencies as a Means to Manage Intercultural Interactions,” Journal of Intercultural Communication, Issue 7.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Stier, J. (2006). “Internationalisation, Intercultural Communication and Intercultural Competence,” Journal of Intercultural Communication, Issue 11, pp 1-12.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Suciu, M. C. (2009). ‘Cultural Diversity, Intercultural Dialogue and Intercultural Effectiveness,’ IBIMA Conference, 4-5 January 2009

Suciu, M.- C. & Trocmaer Neagu, A.- M. (2009). “Students Perception on Gender Equality at the POLITEHNICA University of Bucharest,” Annals of DAAAM for 2009 & Proceedings of 20th DAAAM International Symposium,

Publisher

Suciu, M. C., Trocmaer Neagu, A. M. & Ivanovici, M. (2010). ‘Ethics and Moral Issues within a Multicultural Learning Environment, Intercultural Dialogue, Intercultural Sensitivity and Intercultural Effectiveness,’ Proceedings of QMHE, 2010

Trompenaars, F. & Woolliams, P. (2003). ‘Business across Cultures,’ Chichester, England: Capstone.

Google Scholar

Vasques Scalera, C. M. (1999). ‘Democracy, Diversity, Dialogue: Education for Critical Multicultural Citizenship,’University of Michigan

Google Scholar

http://www.asef.org/index.php?option=com_project&task=view&id=668.

http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/bizchina/201007/19/content_10125806.htm

Publisher

http://www.irsea.ro/

Publisher

http://www.irsea.ro/Asia-in-the-Eyes-of-Europe-research-project/

Publisher