Introduction

Today, Female Entrepreneurship becomes important to economic development. The economic and social benefits of women’s entrepreneurship are very positive for the global economy. Some researchers claim that Female Entrepreneurship could become one of the solutions to the actual economic crisis.

For these reasons, the integration of women in economic development has therefore become a necessity. This explains the increased interest shown by many researchers in the world for the Women Entrepreneurs. The goal is to find ways and means to promote Women’s Entrepreneurship in the world. Thus, the collection of information and data about women entrepreneurs around the world becomes essential to achieve this goal.

According to our literature review, various studies have been dedicated to Female Entrepreneurship around the world. Most of these studies focused on the motivations of women entrepreneurs, their personal characteristics, their relationship with the environment, their management style and the difficulties they face. Some researchers have reported common points to all women entrepreneurs, others researchers point out that some differences exist depending on countries.

Despite the growing popularity of Women Entrepreneurship in Morocco, few studies have been conducted. The lack of knowledge about women’s entrepreneurship in Morocco does not allow us to determine the current situation of the Moroccan female entrepreneur. This lack of information avoids developing and implementing strategies that can help Moroccan women companies to grow more.

The aim of this research is to conduct an exploratory study to present the situation of women entrepreneurs in Morocco. The results of this survey will allow us to identify the profile of women entrepreneurs in Morocco, the characteristics of the companies created and the obstacles they face during the start-up and growth stages of their businesses.

To achieve the above objectives, the study constructed the following research questions:

- What is the profile of women entrepreneurs in Morocco?

- What are the characteristics of the companies they have created?

- What is their relationship with their environment?

- What is the nature of problems faced before, during and after the establishment of their businesses?

- What are the recommendations and solutions to overcome the difficulties encountered?

Theoretical Framework

Definition of the Concept of “Woman Entrepreneur”

Finding a definition of woman entrepreneur is not an easy task since the definitions identified from various schools of thought as well as different areas of research make it difficult to reach a consensus on a distinct definition of female entrepreneur.

Lavoie; (1988) describes the she-entrepreneur, whom he also called the owner-head of company, owner-manager of a company or woman-head of a company, as “A woman who alone or with partners has founded, bought or inherited an enterprise, who assumes the risks and financial, administrative and social responsibilities and participates in its day-to-day management”. In this definition, Lavoie considers purchasing or inheritance to be equally acceptable as founding and establishing a business.

According to Belcourt, Burke and Lee-Goselin Belcourt; (1991) the she-entrepreneur is “a woman who seeks self-fulfillment, financial autonomy and control over her existence thanks to the launch and management of her own business”.

Typology of Women Entrepreneurs

Research in women’s entrepreneurship has prompted a great deal of studies and analyses, proposing ideal types of entrepreneurs. Thus, according to Denieuil; (2005) there are three categories of women-heads of companies:

Women Entrepreneurs: These are women who generally come from wealthy backgrounds, who have certain financial capacities or who possess professional skills or appropriate training. They may also be female heirs who receive the logistic and financial support of the family and take over the family business. They are women entrepreneurs for whom their companies represent a duty of transmission by taking over.

Women engaged in income-generating activities: These are generally individual initiatives from women, the vast majority of whom are disadvantaged. They are women who tend to cope with the difficulties of personal life in a concern for independence and self-fulfillment. The goal of these women is to self-employ and promote their socio-economic integration. Generally, these women have a certain level of knowledge and sufficient training, enabling them to undertake business more easily.

Women who are economically active and who have very limited know-how and training: These are women for whom entrepreneurship does not appear as a choice, but rather a necessity in response to an economic or social breakdown divorce, widowhood, etc.. They are women in a precarious situation whose low incomes serve the satisfaction of basic family needs.

Research on the problems faced by women entrepreneurs

According to several studies, the majority of barriers encountered by women entrepreneurs are categorized into five major issues: 1 access to capital, 2 business performance, 3 networking, 4 training, and 5 work-family life balance. These problems are observed in several countries and experienced by different groups of women entrepreneurs.

Research on access to capital

Lack of initial capital and difficulties in securing financing from financial institutions are often cited as barriers faced by women entrepreneurs. A number of studies Aldrich, 1989 Hurley, 1991 Scott, 1986 Forget, 1997 suggest that financial institutions may be reluctant to support women-led ventures, although women tend to borrow less than their male counterparts. Other researchers have tried to discover the differences between the respective relationships of men and women and their financial institutions. The results of the studies are sometimes contradictory.

According to some studies, women would benefit from unfavourable conditions compared to those granted to men. Thus, Hisrich and O’Brien; (1982) noted in one of their studies that women face difficulties with the banking community, mainly women working in non-traditional sectors.

According to the results of another study conducted in France Orhan; (2001), banks are generally reluctant to lend to small businesses, thus penalizing women entrepreneurs. Lending conditions are more unfavorable for the female entrepreneur. Two variables could be at the source: prejudices of the bankers against the female entrepreneur and the lack of financial skills in the female company. While the studies presented above confirm that women entrepreneurs are discriminated against by banking institutions, other studies show that there is no relative discrimination in access to finance. Thus, according to Riding and Swift; (1990) taking into account size, age, sector of activity and legal status, there is no apparent difference between women and men entrepreneurs and their relationships with financial institutions.

On Performance Research

The performance of firms owned by women has been the subject of several research studies. The literature review shows that the performance of firms varies according to whether they are led by women or by men.

According to several authors, the concept of performance is defined on the basis of three variables: Sales growth, revenue growth and growth in the number of employees. For some authors, if we take these variables into account, there is no difference between the performance of firms owned by women entrepreneurs and those run by their male counterparts. In this sense, Watson; (2003) shows that if we consider variables such as the sector of activity and the age of the firm, there is little difference in performance between the two sexes. The study by Johnsen and McMahon; (2005) reaches the same conclusion. However, according to St-Cyr and Graynon; (2004), the sex of entrepreneurs will not be an explanatory variable of growth, but rather the size of their business that will make it grow or not. St-Cyr and Gagnon; (2003) did not find a positive correlation between the performance of the company and its sector of activity and presented other variables such as participation in business networks, Legal status and form of ownership that would further explain the performance of a company owned by a woman.

Other researchers have been interested in explaining why firms owned by women perform less than their male counterparts. For example, Robichaud, McGraw and Roger; (2005) explain why the causes can be attributed, among other things, to the economic and non-economic objectives that male and female entrepreneurs did set. According to these authors, women entrepreneurs have much lower economic objectives than their male counterparts, thus creating smaller enterprises with less rapid development, the aim being to have the desired quality and lifestyle. In other words, women focus more on personal goals than on financial ones.

Research on Training

Some authors Birley, Al.; (1987) consider that women and men entrepreneurs have similar experience and knowledge, especially in the context of starting up a business, unlike others Lee and Rogoff; (1997) who admit that women entrepreneurs have less knowledge and less management experience.

Menzies, Diochon and Gasse; (2004) report that the training of women entrepreneurs generally does not allow them to create large enterprises and that training in computer science or engineering would allow them to have easier access to larger companies .

Research on Access to Networking

One of the key success factors identified in the success of a woman-run business is its involvement in networks to build peer relationships, develop business opportunities, facilitate access to finance and break the loneliness of the leader.

A number of research reports indicate that women engage less than men in networks. St-Syr; (2001) reports that women tend to underuse networking because of lack of time or interest. Although the data have not been updated, this finding is likely to be still relevant as women entrepreneurs are very busy with the burden of work and family. There is little time left for affiliates to join business networks. Similarly, Cornet, Constantinidis and Arsendei; (2003) explain the low participation of women in the networks as being due to the lack of interest and information.

Research on Family-Work Balance

Concerning the reconciliation between private and professional life, studies have highlighted the difficulties that women entrepreneurs can experience as mothers. Thus, Lee-Gosselin and Grisé; (1990) show that 32% of women entrepreneurs consider that their professional life has deteriorated their personal life and, more particularly, their family and social life. The findings of Schindehutte, Morris and Brennan; (2003) reveal that the business of a woman entrepreneur disrupts her family life. Other authors add that the problem of reconciliation between family and work tends to increase according to the number and age of children. For example, Kirkwood; (2003) shows in her qualitative study of 21 American women that they start their own business only after children enter the school. This confirms the results of Fouquet; (2005), according to which single female directors or widows or divorced women are more creative because they would have fewer family responsibilities.

According to other researchers, maternity can be a factor favoring female entrepreneurship, because it would push women towards the exit of the wage labor. Thus, a new concept is emerging for women entrepreneurs: the Mampreneurship. Several definitions exist in the literature. According to Duberley and Carrigan; (2012), the term Mampreneur refers to any woman entrepreneur who starts a business so that she can both work and look after her young children. These are mothers who create their business during their pregnancy or after the birth of their child. The objective is to better reconcile their life as a mother and their careers- (Froger, 2010).

Female Entrepreneurship in Morocco: a field investigation

Methodology

Within the framework of our study, we adopted a quantitative approach supported by a qualitative approach.

We focused exclusively on women entrepreneurs in the formal sector. We have retained just women entrepreneurs who have created, inherited or taken over a legally registered company with at least a partial ownership and who participate in strategic decisions as well as in day-to-day operational decisions.

The Kompass directory listing women-led enterprises in Morocco was used as a basis for the sample of our study. We were able to create a list of 100 potential respondents working in the following cities: Tangier, Larache, Casablanca, Rabat and Marrakech.

Prior to the survey, potential respondents were contacted by telephone to ensure their collaboration and to count the total sample. A total of 80 people were in favor of our solicitation.

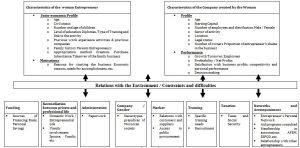

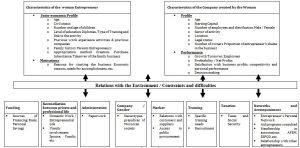

Data collection was conducted using a questionnaire in accordance with the selected analysis model. The model of analysis used to develop the questionnaire is inspired by a number of similar studies : Tracy; (2009,) Kounta; (1997), Lee_Gosselin; (2010), Cholette; (2005). This model is based on 3 components: the Entrepreneur, the Company created and the relations with the environment (Figure 1).

An introductory letter containing the research objectives accompanies each questionnaire. The questionnaire was also available on the Web from Google Forms http://goo.gl/forms/MMWI5SrSje.

The questionnaire consists of 49 questions and includes closed and open questions. The questionnaire is divided into 3 sections. The characteristics of the entrepreneur are discussed first. This section is based on questions on age, civil status, number of children, level of education, type of training, last occupation and previous experiences. In this first section, respondents are also asked to give their reasons for starting a business. In the second section, we are interested in the characteristics of the companies created by the respondents: age, size, location, starting capital, sector of activity and their performance.

Finally, in the third section, we address the constraints and difficulties encountered by the respondents.

A pre-test of the questionnaire was carried out with 5 respondents. This pre-test allowed to validate the wording of the questions as well as the answers choice and to estimate the time required to answer the questionnaire.

After three months of investigation from November 2015 to January 2016, we obtained 80 questionnaires including those of the pre-test.

Figure 1: Theoretical Framework

Results

The Socio-Demographic Profile Of The Participants

The following section describes the socio-demographic profile of women entrepreneurs who participated in our survey. The main variables identified were age, civil status, number of children, academic background, family background and previous experiences.

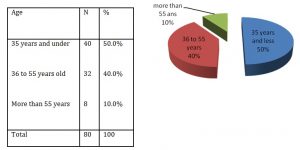

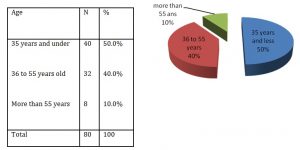

Age

As shown in Figure 2, half of our respondents are under 35 years of age. Those between the age of 36 and 55 represent 40% of our sample. On the other hand, female entrepreneurs of 55 years and more account for only 10% of all female participants. The youngest entrepreneur met was 24 years old and the oldest one 63 years. The average age of our respondents was 39.7 years

Figure 2: Age of Entrepreneurs

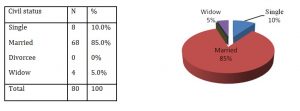

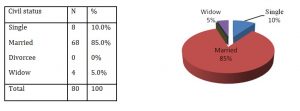

Civil Status & Number of Children

As illustrated in Figure 3, a large majority of our respondents are married (85.0%). Of the

Figure 3: The Civil Status of Entrepreneurs

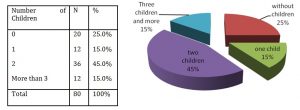

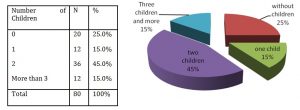

Our respondents who are mothers have 1 to 5 children. 12 women (20%) had only one child, 36 (45%) had two children and 12 women (15%) had a family of three or more children. Only 20 participants (25%) reported that they had no children.

80 women entrepreneurs who responded to the questionnaire, 60 75.0% had at least one child (Figure 4). Our respondents are therefore more married and more mothers.

Figure 4: Number of children per Entrepreneur

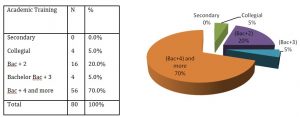

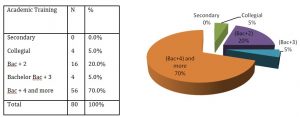

Academic training

The majority of women surveyed have a higher level of education (Figure 5). In fact, 76 women (95%) have a university degree; Bac + 2, Bachelor’s, Bac + 5 and higher. Two

respondents have a college diploma. Moroccan women in general are more and more educated and higher education could theoretically offer them more skills that can be used in their business. We also found that 52 (65%) of the 80 participating women had a specialization in direct relation to the type of activity they perform.

Figure 5: Level of training for Entrepreneurs

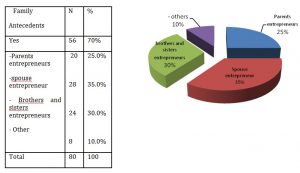

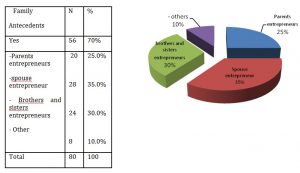

Family Antecedents

The family members of our respondents had a direct influence on the creation of their business. Among our 80 respondents, 56 (70%) say they already have an entrepreneur member in their family circle (Figure 6). In fact, 25% of respondents have a relative in business, 35% have their spouse as entrepreneur and 30% have entrepreneurs among their brothers or sisters.

Figure 6: Presence of entrepreneurs in the family

Previous Experiences

As shown in Figure 7, 68 of our participants (85%) have already worked before starting a business. 52 of them (65.0%) say that the activity of the company created is linked to their previous experience. Thus, it can be confirmed that professional experience is a stepping stone to the creation of a company for a large part of our respondents.

Figure 7: Previous Experiences of Entrepreneurs

The Profile of Created Companies

The section below describes the business profile of our respondents. The main variables observed are age, legal status, personnel, sector of activity, ownership, legal structure and turnover of the company.

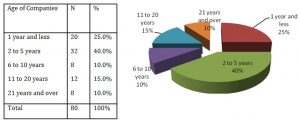

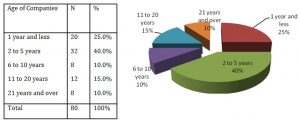

Age of the Companies

As shown in Figure 8, our respondents’ firms are aged 1 to 42 years. 52 out of 80 of our companies (65%) are very young and are under 5 years old and 20 of them (25.0%) are in their first year of operation. Firms aged 21 and over account for only 20% of our sample. The average age of our companies is 8.87 years.

Figure 8: Age of companies

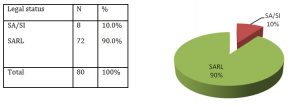

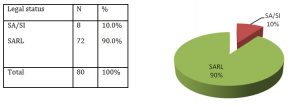

Legal Form

The most common form of our companies is made up of SARL 90% (Figure 9). The choice of this legal form is justified by its simplicity and its adequacy to SMEs as well as the flexibility of its status and the social capital which remains lower with facilities in terms of blocking the creation. However, a lower percentage, 10% of individual companies and public limited companies can be explained by the great demands and the great formalism in the creation and management of this type of company.

Figure 9: The Legal Form of companies

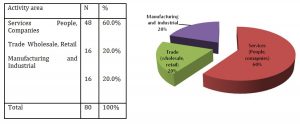

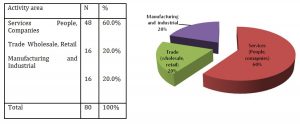

Business Line

As shown in Figure 10, 60% of our respondents’ businesses are concentrated in the service sector. Wholesale and retail trade follow to account for 20%, whilst manufacturing and construction equally account for 20%.

Figure 10: The Business Sector for Enterprises

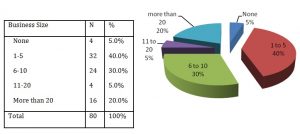

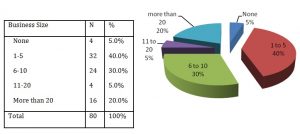

Size of companies

Regarding the size of our businesses, 56 companies (70%) have fewer than 11 employees (Figure 11). 32 companies (40%) are operating with less than 5 employees, 24 companies (30%) have between 6 and 10 employees, Four employ 11 to 20 employees, and 16 (20%) have more than 20 employees. Four of our female respondents have no employees.

Figure 11: Size of Companies

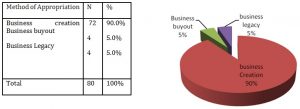

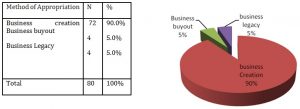

Mode of appropriation

Business ownership remains the mode of appropriation favored by 90% of our respondents (Figure 12). Four of our respondents seized a business opportunity by buying their business. Four others have appropriated their company by inheritance.

Figure 12: Business Ownership

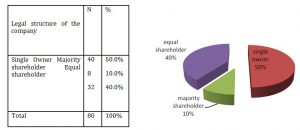

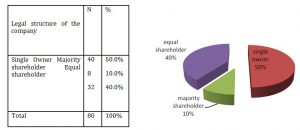

Legal Structure of the Company

Half of our respondents reported that they were sole owners of their businesses (Figure 13). The company is also used as a legal structure by our respondents 40% as equal shareholder and 10% as majority shareholder.

Figure 13: The Legal Structure of companies

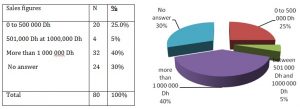

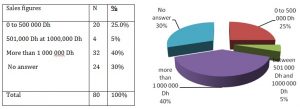

Annual turnover of Enterprises

Our respondents report turnovers that differ greatly from one company to another (Figure 14). Some 40.0% say they have incomes exceeding 1 million DH/100,000 USD, while others (25.0%) report a turnover of less than 500,000 DH/ 50,000 USD. Nevertheless, the average turnover of our respondents’ companies is around 1 455 000 DH per year, 145 500 USD. It should be noted that 24 respondents did not wish to report their annual turnover.

Figure 14: Annual turnover of companies

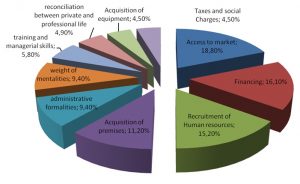

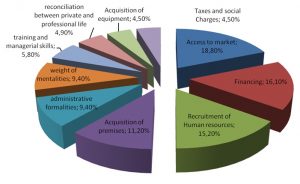

Problems Experienced

We identified ten issues that could be addressed in our research. These include : financing, acquisition of premises, acquisition of equipment, administrative formalities, taxes and social charges, reconciliation between private and professional life, access to the market, recruitment of human resources, training, and the weight of mentalities. Figure 15 presents an overview of the issues faced by our respondents.

Difficulties in accessing the Market represent the main problem faced by our respondents with 18.8%. Indeed, according to our interviewees, the penetration of the economic markets remains a challenge in itself for several of them. Some reported that they were victims of much discrimination in terms of access to business markets and public procurement. Others have claimed a quota for access to public procurement. Selection mechanisms should therefore be modified so that entrepreneurial opportunities generated by women are more likely to have better chances to access different markets.

Then come the difficulties related to the financing with a percentage of 16.1%. Most of our respondents’ business financing 48 out of 80, or 60% is made up of personal and family contributions. 32 out of 80 respondents applied for a bank loan, 20 of which were rejected. The main reason cited by our respondents is related to the guarantees required by the Moroccan banking system. As for the sexist discrimination faced by the Moroccan women entrepreneur when applying for a bank loan, almost all of our respondents (95%) refute any discrimination based on their gender and state that bank decisions are based essentially on the soundness of their files, in particular in terms of guarantees. They find that the guarantees required by Moroccan banks are too high and that unfortunately banks do not take into consideration other criteria such as professional experience, diplomas and skills.

Figure 15: Problems of women surveyed

Difficulties related to the recruitment of qualified resources are experienced by 15.2% of our respondents. 11.2% of our respondents also experienced difficulties related to the acquisition of the premises.

Other participants (9.4%) experienced difficulties related to administrative formalities. Indeed, as everywhere in the world, any business creation in Morocco requires a series of administrative, legal and fiscal acts. The intervention of the administration constitutes in itself a source of difficulties which slow down, weaken or prevent the creation of a company. Corruption, slow administrative formalities and bureaucratic attitudes are all obstacles mentioned by our respondents.

As for the problem related to the weight of mentalities felt by 9.4% of our respondents, they reveal that they suffer on a daily basis from harassment, lack of credibility and reluctance of the various partners, customers, suppliers, etc.. For others, the family environment also seems to be an obstacle, although legally the Moroccan woman is no longer obliged to ask her father or her husband for authorization, for example in the case of repetitive travel or in case of meetings with customers at late hours. These social practices are justified by the traditions and customs that characterize Moroccan society, and which impose on a woman the respect of rules of conduct towards her family and society.

Moreover, according to our study, the reconciliation between work and family life does not seem to represent problems for our respondents. 68 of our respondents (85%) say they can reconcile between the two. Most of our respondents stated that, regardless of the age of their children, reconciling work and privacy remains a daily organizational issue. Our respondents also reported using a housekeeper who would take care of both household chores and their children. Some of our respondents can also rely on their family circle parents and in-laws to keep their children while they work.

Other constraints of lesser importance are also experienced by our participants. These are mainly tax difficulties or those related to the acquisition of equipment.

Conclusion

Our problematic, which is built on a finding of poor knowledge of Moroccan entrepreneurs, led us to a field survey. The objective is to determine the typical profile of the Moroccan entrepreneur, the characteristics of the company created as well as the problems experienced.

According to our findings, the Moroccan entrepreneur is a married woman, aged between 28 and 40 with a number of children ranging from 1 to 2. She has a higher education level. The type of activity she carries out is related to the training she has acquired. She is often surrounded by entrepreneurs of her family, spouse, father or mother, brothers or sisters. She gained experience before embarking on business.

Regarding the profile of the companies created, Moroccan women’s companies are small in terms of turnover and number of employees. They generate an average annual turnover of around 1,455,000 DH / 145,000 USD. They employ an average of about twenty employees. There is a strong concentration of these companies in the service sector. The majority legal form consists of limited liability companies.

Thus, our survey does not escape the observation of other researchers on the profile of the entrepreneurs and the characteristics of the companies created.

At various levels, women entrepreneurs in our sample are confronted with 10 problems: financing, acquisition of premises, equipment purchasing, administrative formalities, taxes and social charges, reconciliation between private and professional life, access to the market, recruitment of human resources, training, and the weight of mentalities.

To our surprise, access to the market remains the biggest problem faced by female entrepreneurs surveyed, while access to financing was considered by previous research to be the main difficulty encountered by women entrepreneurs in Morocco (Afem, 2004: Bousseta, 2010). The results of this research demonstrate that women entrepreneurs in Morocco face a new problem that is less well known in the literature.

It should be noted that this research has limitations, notably the absence of official statistics based on gender, which prevents us from comparing women entrepreneurs with their male counterparts. Another limitation is related to the reluctance of a large number of women entrepreneurs to respond to our questionnaire.

References

- Aldrich, (1989). In pursuit of evidence: sampling procedure for locating new business, journal of business venturing, vol 4,1989, p.367-386.

- Birley, (1987). Do women entrepreneurs require different training ? American journal of small business, summer, 27-35.

- Boussetta, (2011). Entrepreneuriat féminin au Maroc : environnement et contribution au développement économique et social. Investment climate and business environment research report no. 10/11.

- Bouzekraoui & D. Ferhane, (2014). Les obstacles au développement de l’entrepreneuriat féminin au maroc. XXXème journées du développement ATM 2014. Colloque international sur l’éthique, l’entrepreneuriat et le développement. University Cadi Ayad Marrakech. Les 29, 30 et 31 mai 2014.

- Burderre, (1990). Black and white female small business owners in central ohio : a comparaison of selected personal and business characteristics “. Phd thesis, ohio state university.

- Cadieux l, (2002). Le processus de la succession dans les entreprises familiales : une problématique comportant des défis estimables pour les chercheurs, 6° congres international francophone sur la pme – octobre – hec – Montréal.

- Cholette, (2005). Enquête sur les femmes entrepreneures et les travailleuses autonomes en Outaouais, comite de travail sur l’entrepreneuriat féminin en Outaouais novembre 2005

- Cornet, a. & Constantinidis, c , (2004). Entreprendre au féminin: une réalité multiple et des attentes différenciées. Revue française de gestion, 30151, 191-204.

- Ducheneaut, (1997). Les femmes entrepreneurs a la tête de pme, in conference de l’ocde sur les femmes entrepreneures a la tête de pme : une nouvelle force pour l’innovation et la création, Groupe esc rennes, euro pme, avril 1997.

- Eurostat, (2010). Enquête sur les forces de travail, les organisations couvertes sont les sociétés et petites entreprises et les postes couverts les dirigeants, directeurs et gérants, eurostat, 2010.

- Fiducial, (2006). Rapport de l’observatoire fiducial de l’entreprenariat féminin, janvier 2006, http://www.fiducial.fr/

- Forget, (1997). Entreprendre au féminin; rapport du groupe de travail sur l’entrepreneuriat féminin. Quebec: groupe de travail sur l’entrepreneuriat féminin.

- Fouquet,( 2005). Les femmes chef d’entreprise: le cas français », travail, genre et sociétés, n°13, avril, p.31-50.

- Genevieve bel, (2009). Rapport de Geneviève bel, 2009, « entrepreneuriat au féminin », rapport et avis du conseil économique, social et environnemental.

- Hernandez, 1997. Le management des entreprises africaines, l’harmattan, paris.

- Hisrich, (1987). Women entrepreneurs : a longitidunal study “, frontiers of entrepreneurship research, babson college.

- Hisrish, (1991). Entrepreneurs hip: lancer, élaborer et gérer une entreprise, édition. Pp.6162.

- Holmquist, (1990). What’s special about highly educated women entrepreneurs?, entrepreneurship and regional development, 2l, 181-193.

- Hurley, (1991). Incorporating feminist theories into sociological theories of entrepreneurship, paper presented at the annual meetings of the academy of management, Miami, fl.

- Kirkwood, J. & tootell, b, (2009). Is entrepreneurship the answer to achieving workfamily balance? Journal of management and organization, 143, 285, 2009.

- Lafortune, a., St-Cyr, (2000). La perception de l’accès au financement des femmes entrepreneures, rapport d’expertise présente au ministère de l’industrie et du commerce, 2000, 72 pages.

- Lambrecht, (2003). Entrepreneuriat féminin en wallonie, centre de recherche pme et d’entrepreneuriat – universite de liege et centre d’etudes pour l’entrepreneuriat, ehsal, 2003, 231 pages.

- Lavoie, (1984). A new era for female entrepreneurship in the 80s. Journal of small business, pp 34-43, canada.

- Lavoie, (1988). Les entrepreneures : pour une economie canadienne renouvelee, conseil consultatif canadien sur la situation de la femme, ottawa, fevrier 1988, 64 p.

- Lee, (1996). Comparison of small businesses with family participation versus small businesses without family participation:an investigation of differences in goals, attitudes, and family business conflict. Family business review, 9, 423-437.

- Lee, m.s., Rogoff, e. , g. (1997). Do women entrepreneurs require special training?an empirical comparison of men and women entrepreneurs in the united states, journal ofsmall business and entrepreneurship, 141,4-29.

- Lee_Gosselin, (2010). Helene lee-gosselin. Realites, besoins et défis des femmes entrepreneures de la région de la capitale nationale. Février 2010.

- Legare, (2000). L’entrepreneuriat feminin, une force un atout : portrait statistique des femmes entrepreneures. Quebec: gouvernement du quebec, ministere de l’industrie et du commerce, chaire de developpement et de releve des pme.

- O’brien, (1981). “the woman entrepreneur from business and sociological perspective”, frontiers of entrepreneurship research, 1981, 21 to 39.

- Ocde, (2004). Entreprenariat féminin : questions et actions a mener. 2eme conférence de l’ocde des ministres en charge des petites et moyennes entreprises pme, istanbul, turquie 3-5 juin 2004.

- Orser, b. Et foster, m. D (1994). Lending practices and canadian women in microbased business. Women in management review, 95, 11-19, 1994.

- Richer, (2007). L’entrepreneuriat féminin au Québec : dix études de cas Montréal : presses de l’université de Montréal.

- Riding, a. L. Et swift, c, (1990). Women business owners and terms of credit: sorne empirical findings of the canadian expérience. Journal of business venturing, 55,327-340.

- Salmane, (2011). Les femmes chefs d’entreprise au Maroc. 11eme congres international francophone en entrepreneuriat et pme.

- Scott, (1986). Why more women are becoming entrepreneurs. Journal of small business management, 24 4, 37 44.

- St-syr, (2002). L’entrepreneuriat du secteur manufacturier quebecois : caracteristiques et acces au financement, 6eme cifpme, hec-montreal, octobre 2002.

- Tracey, (2009). Les obstacles et les solutions des femmes entrepreneures des régions ressources du Québec. Mémoire présenté a l’université du Québec a Trois-Rivières. 2009

- Watkins, 1983. The female entrepreneur : her background and deteminants of business choice some british data. Frontiers of entrepreneurship research, babson college.

- Welsh, (1982). The information source selection decision : the role of entepreneurial personality characteristics ” journal of small business management.

- Werbel, (2010). Work family conflict in new business ventures: the moderating effects of spousal commitment to the new business venture”, journal of small business management, vol. 483, p. 421-440.

- Zouiten, (2007). L’entrepreneuriat féminin en Tunisie. Dynamiques entrepreneuriales et développement économique. L’harmattan, p 101-117.

- Werbel, 2010. Work family conflict in new business ventures: the moderating effects of spousal commitment to the new business venture”, journal of small business management, vol. 483, p. 421-440