Introduction

To consider the values and behavior of young employees or students today, means taking an interest in the concerns peculiar to the different generations and the needs and expectations they express. By generation, is meant a group of individuals in a given context together who share the same history and relatively similar experiences. More precisely, a generation designates a sub-category of the population whose members have almost the same age or have lived in the same historical period. They share a certain number of practices and representations owing to having the same age and belonging to the same epoch.

Sociologists have always been interested in the generations as they traverse time. Five types of generations have been distinguished since the Second World War (Bourhis, 2006): the seniors born before 1946; the baby boomers born between 1947 and 1963; generation X born between 1964 and 1977; and generation Y born between 1978 and 1992. This last generation is described as a population of young students or young graduates at the start of their careers. Also known as the Internet or “E” generation they have developed skills in this field while modifying their relations not just to society but also to the professional world; and lastly, generation Z born after 1993.

The purpose of this article is to look more precisely at one of these generations – the generation Y. In France, the expression “Generation Y” means persons born between 1978 and 1992. Invented in 1993 by the magazine Advertising Age, the expression “Generation Y” designates the generation following “Generation X”. Other expressions are commonly used to refer to this generation. In particular, they are called “Echo Boomers” as many of them are the children of baby-boomers or “Children of the millennium” (“Millennials” in English) linked to their date of birth. Americans also use the expression “Digital Natives” to underline the fact that these children were born with a computer or quite simply the diminutives “GenY” or “Yers”.

In France the generation Y comprises about 13 million persons, i.e. nearly 21% of the population (INSEE – Institut national de la stastique et des études économiques – National Institute for Statistics and Economic Studies). It is the most numerous generation since that of the baby-boomers. As a comparison, the Generation Y totals about 70 million persons in the United States and 200 million in Chinai .

i http://lagenerationy.com/2009/03/21/la-generation-y-vue-par-les-drh/.

In a context of retirement age population replacement, studying the generation Y has become essential for business. A labor shortage is foreseen and organizations will increasingly come face to face with recruitment, intergenerational management (Bourhis, 2006), and employee loyalty problems: “highly informed and naturally prepared for the new technologies this generation Y is also an opportunity for enterprises. Faced with the challenge to renew their workforce – which in France will come to a head from 2010-2015 – recruiters are racking their brains working out how to hire them and keep their loyalty” (Relinger, 2008).

The advantage of categorizing by generation type is to enquire into the diversity and differences of each generation’s relations with information and communication technologies (ICT). Thus, generation Y is recognized as being seriously predisposed for everything concerning ICT; that is why in taking an interest in generation Y we place these ICT and e-management issues at the forefront of the enterprises’ concerns. Following the studies of Jacob and Harvey (2005), it is discernable that adaptations are necessary for taking into account the differences potentially existing between generations from the point of view both of managing induction, the work itself, and productivity and of managing commitment, professional development, and conflict management. Hence, our study tends to show e-management tools and methods can be elements organizations can use to manage this new generation.

All the same, there are no settled opinions on the subject and some say the generation is not as different as may be thought. So what about this generation Y? What are its main characteristics that enable it to be described and how do its members behave within organizations? What relations does this generation have with all the ICTs and how may “e-management” be involved? The answers to these various questions will thus make it possible to put a finger on the specificities of this generation’s relationship with the ICTs – if they exist – and so on the principal managerial issues revealed as far as e-management tools and methods are concerned. In short, the question this article discusses may be formulated as follows: what are the characteristics of this “E-Generation” and how can the management tools and methods used in organizations be adapted to them?

The answer to this question means accomplishing two objectives: to define the e-generation’s main characteristics and its behavior at work and to present the implications this may have in terms of administrative and management tools and methods. Accordingly, an exploratory empirical study has been carried out. It consisted of a qualitative survey to determine the profiles of this generation and the working and management methods it would be useful to develop in the light of these profiles. 30 focused interviews were administered to a population of young employees and students and 10 to line-managers and heads of human resources. Totally re-transcribed, these interviews underwent both a computer assisted qualitative data analysis and a manual contents analysis. Thus, it will be possible to use verbatim extracts from the interviews to illustrate the conclusions and analyses of our studyii .

ii Each verbatim will refer to extracts from interviews numbered from 1 to 30 (number of sample interrogated): INTER.1 will concern for example extracts from the report for interview No.1

Taken as a whole, the results of these surveys will throw a light on why the e-generation is such a topical theme and on the principal managerial issues dealing with this generation entails. Indications and solutions to prefer when managing this population are also suggested; since many human resources managers admit to having difficulties in implementing HR practices for young people (Laize, Pougnet, 2007).

We search, therefore, to describe this generation by putting in perspective all the aspects connected to using information and communication technologies and what this implies for organizations (1). Thus, we show that management tools and practices seem more suitable for this e-generation (2).

1. The Generation Y: The Generation of the “E” and the Issues It Represents

In France, the expression “Generation Y” designates the persons born between 1978 and 1992. It is the most numerous generation since the baby-boom (Pouget, 2008). It represents about 21% of the French population (Pouget, 2008).

This generation is mainly characterized “by the fact it was born in contact with the new communication technologies, around which a whole communitarian ideology has developed in which the individual and his community take back their rights, thereby short-circuiting the traditional systems of legitimacy” (Gleyen et al., 2003).

After a presentation of the various characteristics of this generation (1.1) we insist on its representations (1.2) as seen from how it understands the “e” (via the web especially) before identifying the various relations this generation has with work and the Enterprise (1.3) and, lastly, revealing their major issues (1.4).

1.1. The Characteristics of the Generation Y

The aim of this first part is to understand the personal characteristics of the individual members of generation Y. Here we analyze the generation’s essential traits, based on the results of our exploratory survey, through several key queries: who are the new entrants onto the labor market? What are they looking for? What are their needs?

Globally, the members of generation Y have individualistic, consumer, and zapping behaviors (Laize, Pougnet, 2007). As Benjamin Chaminade underlines, on his blog dedicated to the subject, the principal characteristics of Y culture are: individualism, interconnection, impatience, and inventivity. Nevertheless, “the diagnostic is not as obvious as all that. Certain enterprises attribute the same values of enthusiasm and dynamism to the young as before. Others refer to different values” (Rose, 2006: 14).

In this way, two points will be discussed in this first part: the Ys’ new ways of life (1.1.1) and the relations they have with change (1.1.2).

1.1.1. New Ways of Life

Generation Y has changed its way of life fundamentally. Whereas the baby boomers lived to work, the Ys work to live. They seek the best possible balance between professional and private life, being quite prepared – if need be – to change work and region to keep this balance.

“As for me, what counts is work of course but my personal life too. I couldn’t care less about working where I studied so long as I can find this balance”. INTER.2

This is one of generation Y’s characteristics: they are avid for novelty; they are also called the discoverers.

“What I want is to get around – something new – and I don’t want to be bored by my work or else I’ll leave.” INTER.5

Whether in their professional or private sphere they fight against routine and search for new things to feed their adaptive capacities. They are also open to the world and take an interest in different cultures – which makes them more tolerant than generation X. This open-mindedness also holds good for new ways of life: flat-sharing, rent-sharing, etc.

“We must look at generation Y differently – it is magic; it is full of potential”. “They need to work in groups; they are innovative. They produce and love it”. Gino Andreetta, head of HR GO Club Méditerranée iii

iii http://lagenerationy.com/2009/03/21/la-generation-y-vue-par-les-drh/.

These various elements of ways of life concern the sphere of both private and professional life – which constitutes a major issue for the necessary administrative and management practices.

1.1.2. Change

Generation Y is the generation of change: it has no fear of the uncertainty inherent in it. Consequently, it is difficult to keep this generation’s loyalty, both in the enterprise and its consumption habits.

“We were born with change and we young people love it when it moves. You can never tell, you say, but that’s what makes it interesting, you can’t know everything and that adds a pinch of spice to everyday life.” INTER.30

Change is a particular feature of this generation; which is explainable by the economic and social context the generation evolves in: “digitalization” (Internet) and development of family ruptures:

“Those said to belong to this generation are as comfortable with change as fish in water. They create change, going from one brand or job to another. They flourish in ambiguity and uncertainty – environments in which many baby-boomers are not at home at all. Of course, this is an attribute of youth but generation Y aspires to change the world like their parents. Except that this time they hope not to toe the line” (Chaminade, 2007).

The new ways of life this generation favors, as well as, the search for permanent changes is also accompanied by noticeable evolutions in the social representations this population expresses.

1.2. New Kinds of Social Representations

Generation Y perceives human relationships, especially, through computing and digital tools such as Web 2.0. So it is interesting to realize that these tools are not without effects on the perceptions young people may have and the expectations they formulate in both their private and professional life.

1.2.1. Definition of the Web 2.0

Three phases are to be noted in the network’s evolution (Bourliataux-Lajoinie, 2007):

- The Web 0 (~1965-1995): the network establishes itself; not much content exists; access is reserved to the initiated – researchers, the military. The network is supplied by and for its users. The network’s “philosophy” is born: liberty (of exchanges and ideas), gratuity, knowledge pooling;

- The Web 1.0 (1996-2002): the network is stabilized technically; the graphic layer is in place; it is the end of CLI for ordinary members of the public who discover the power of this collaborative tool. Businesses develop communication strategies by searching to make site content profitable, and the notion of pay-for information becomes more important. The dominant logic tends towards site profitability (subscription payment, financing through advertising) and site content control. Businesses use the web as a new institutional or brand communication medium;

- The Web 2.0 (~2003): the profitability based economic model has reached its limits; it is not abandoned but it is obvious it cannot have the network all to itself. The enterprises structure and make available contents generated by net-users for net-users (www.youtube.com). Profits come from functions ancillary to the core of the enterprise’s business. The network is taken in hand by its users. Pooling gives users the whip hand as against the enterprises; blogs and forums serve as public tribunes for consumers’ experiences who become consumer-players on the web. Technically, the break between Web1 and Web2.0 is characterized by the emergence of new languages (in particular flash and ajax) that allow great interactivity by favoring personalization between site and user.

Generation Y has grown up using the Internet and this substantially influences the expectations and needs it expresses – potentially having powerful effects at the managerial level.

1.2.2. Consequences and Effects on Generation Y Representations

The medium’s intrinsic characteristics were quickly adopted by this population: liberty, gratuity and pooling. On this topic, two examples illustrate this adaptation to the web’s fundamental values: illegal downloading of music, and using digital social networks (DSN). The latter is not without influence on how to envisage the management of this population, who paradoxically are individualists but want to belong to communities.

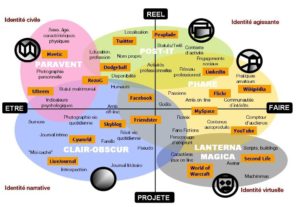

The example of digital social networks is more complicated to analyze – generation Y having begun its professional career and – to a certain extent – its social life with this tool. In his study Cardon (2008) proposes a cartography of digital identity on the DSNs. Two dimensions have been chosen to map the behaviors: self-exteriorization and self-stimulation. Within this framework, both these elements are essential in the management practices businesses will implement for this population; the businesses that will be able to foster these two values through their management practices, tools, and systems and be able to make it known, will best be able to attract this generation and keep it loyal.

The first of these dimensions is directly comparable to studies on perceived image and intended image in marketing; presence on the DSNs is measured here through the exteriorization – indeed the exhibition – of the values in the members’ profiles. This touches on the issue of the image this generation wishes to give of itself through their presence in these DSNs (number of photos registered, tagged, number of friends, etc.). The second dimension is self-simulation; Cardon (2008) defines it as “self-simulation characterizes the tension between the traits that refer to the person in his real life (everyday, professional, with friends) and those referring to a projection or a simulation of the self, virtual in the basic meaning of the term, which allows people to express a part of or a potentiality within themselves.”. The interactions between private and professional life are, therefore, essential for understanding this generation and its effects is important on what the latter express what they expect from enterprises.

With these two dimensions, a typology is presented that makes five segments appear: “The screen, chiaroscuro, the lighthouse, the post-it, and the magic lantern”:

Fig 1. Digital Identity and Digital Social Networks (source: Cardon, 2008).

The detail of these types is interesting in so far as it helps to understand those who belong to them and enable the enterprises to respond to the generation Y’s needs and expectations better. In this way, the management systems can be directed towards suitable methods and tools by taking into account the different values of each of the types according to their principal characteristics:

- The screen: they use the DSNs offering a filter before contact: the typical case is a meetic type network where the adherents pre-select one another through a very complete data sheet ;

- Chiaroscuro: for them the DSNs are an extension of close family and friendly relationships. They only share information with a close circle; they have no desire to exteriorize their life via internet;

- The lighthouse: they exteriorize on the network a lot, show, and display the size of their network of friends, their creations (texts, photos, etc…) and express the wish to share and defend their tastes (Flickr, Myspace, Youtube);

- The post-it: They make their presence on the network very visible but only for their “friends”; they create for themselves a bubble of intimacy (the mutual circle of friends). A strong idea of territory exists – whether physical (via geo-tracking applications such as latitude) or conceptual (a tacit recognition of the individual’s abilities);

- The magic lantern: the most symbolic form of using the DSNs: the user creates his avatar while ignoring all real-life considerations; he becomes what he wants to be. This kind of behavior is very common in Second Life type virtual worlds or Wow iv .type MMORPG v

iv Wow is the acronym for World of Warcraft, this on-line role-play grouped together about 12 million players at the start of 2010.

v MMORPG is the acronym of Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Game, these are on-line games involving thousands of users.

If these different types can orient the enterprises’ management systems (see part 2.), they also strongly affect the relations this generation can have with work and the enterprise.

1.3. Generation Y in its Relations to Work and the Enterprise: Presence of Strong Values

Generation Y’s behavior at work is often summed up as follows: “they want an interesting, evolving, formative job, but reject routine, boredom, and restrictions” (Laize, Pougnet, 2007: 3). According to a study by the APEC (Association pour l’Emploi des Cadres – Association for Managers’ Employment) in 2009 work is a value supporting personal fulfillment for the under 30s.

“Of course, I want to have an interesting job – it’s important for my well-being and those who believe that we young people couldn’t care less are wrong.” INTER.18

“I shall never choose a job that bores me, it must change and move.” INTER.26

In other words, thinking about what this generation expects and needs entails the issue of renewing the human resources management systems inside the enterprise: rethinking how a business is to recruit, integrate, keep loyal, remunerate, and plan the careers of members of this type of population becomes essential.

This generation Y, thus, has many characteristics and values that allow a better grasp and understanding of how it relates to work and the enterprise.

1.3.1. The Strong Presence of Technologies

Prensky (2001) introduces the term “Digital Natives” to speak of this generation for whom the Internet is not a mere tool for information but essentially a means of communication, expression, and encounter for creating social connections. As progress advances, people are attracted by the Internet at an ever more precocious age. These individuals have grown up with the popularization of the personal computer (APEC, 2009).

As a whole, the communication media match the generation Y’s need for instant expression. Members of the generation can use them to say what they feel without worrying about crossing the “t”s and dotting the “i”s. The desire to express overrides the manner – as certain exchanges by SMS or MMS prove.

Furthermore, generation Y has a strong sense of community identity, comparable to tribes. They strengthen this identity as they meet one another; as they go through life these young people keep contact with the people they have met.

“Thanks to facebook or Twitter you never lose anybody. You end up communicating with everyone, everywhere, and whenever; in fact, you travel all over the world with a few clicks.” INTER.22

In order to reach this goal, they take advantage of the social networks arriving on the Internet -Facebook, Myspace, Twitter, etc. The web 2.0 has entailed new practices in communication (APEC, 2009). The Ys say what they think more directly and spontaneously than their elders. These factors are not without effect on the emergence of professional discussion forums and employee blogs that are sometimes taken over by the enterprises themselves.

“When we have something to say we can say it through forums and blogs. We need to say it the way it is – it’s more transparent. And we share the information too.” INTER.17

The rise of the Internet also materializes generation Y’s need to be free:

in a “click” it is where it wants. This need for liberty also makes for harsher relations with parents – though the individuals of this generation stay living with their parents for longer and longer.

“All these digital tools are our way to get away from it all, and what’s more avoid our parents’ authority. It’s our world.” INTER.05

The development in ICTs also inverts the balance of power within the enterprise. Before – “the enterprise trained its workers on the technologies that would later become familiar to the general public. Now, it is often the employees who introduce mobility tools into the firm” (Vincent, 2010: 28).

1.3.2. The Importance of Individualism and Self-Fulfillment

Individualism is one of the “4i” used by Benjamin Chaminade on his blog to define the generation Y:

“individualism appears as a ‘tidal wave’ in contemporary society enveloping key values such as individual freedom, moral autonomy in relation to traditional standards, self-knowledge, and valuing personal well-being” (APEC, 2009: 20). Nevertheless, Rose (2006: 14) nuances these factors: “young people’s individualism stems from society’s increasing demand for strong individual responsibility. Young people tell us how our society has changed”.

Besides, often from single-parent families (phenomenon of break-down in family structure) these only children are used to getting what they want, of being considered, being listened to, and having their needs and desires rapidly and systematically responded to. So the individual is at the centre of attention even if this individual paradoxically needs to become part of Facebook or Linkedin type virtual communities.

A primacy of the personal sphere is also evident, resulting in a strong search for fulfillment. This means trying to achieve a balance between professional and private life, as well as, reconciling individual and collective rhythms. This point is not unrelated to the search for strong sociability at work and close peer relationships in the professional sphere.

“Thanks to the networks, whatever they may be, you can at least say what you do. True, it’s a bit self-centered but at least you can sometimes show you’re different and that you do and say things that aren’t too stupid.” INTER.02

“As for me, work isn’t my life; it’s important, of course, but do you think someone who isn’t happy can be happy in his work? The time when only work counted is over.” INTER.10

All these factors relating to individualism and self-fulfillment explain why this generation has a certain conception of life and relation to work. Work, in fact, is not the only reference in their universe and the sole reference value; one is quite prepared to accept work is not the only source of fulfillment and well-being.

“Generation Y is a paradoxical generation nourishing both a strong desire for autonomy and a refusal to enter adulthood, which manifests strong individualism and ends up in sometimes improbable communities” “This generation imposes its conditions and expects a lot in terms of recognition and quality of life. It wants the enterprise to give it individual solutions, especially as concerns career development”. Yves Desjacques, head of HR, Casino vi group.

vi http://lagenerationy.com/2009/03/21/la-generation-y-vue-par-les-drh/.

1.3.3. The Relation to Time and Space

Despite the reputation for constant fickleness they often have in both their professional and personal life a study by the CEGOS (Commission d’Étude Générale d’Organisation Scientifique) in 2009, reports nearly ¾ of generation Y young people will not leave their enterprise if it meets their expectations and lets them develop.

“It is said we aren’t stable, but that depends because I don’t see why I should change if I’m happy with my firm. If I can combine my personal with my professional life I’ll stay, as soon as I can’t I’ll go.” INTER.19

“So long as the enterprise has things to offer me and takes what I want into account I’ll stay loyal.” INTER.02

The influence of the context of instability must certainly be taken into account (APEC, 2009). They are very much affected by the current insecurity and unemployment (Laize, Pougnet, 2007). The young employees favor internal mobility: changing job within the same sector or enterprise (CEGOS, 2009).

“Even if I’m aware unemployment affects young people I still want to move around. So I’m looking for a firm big enough to be able to get around and not stay in the same job. I’d like to move between different firms but I’m aware circumstances aren’t very favorable.” INTER.13

1.3.4. The Relation to Power

In relations with power and line-management the elements are also quite characteristic. Generation Y is aware of the importance of making a commitment in professional life, especially at its beginning.

“People think we don’t have our feet on the ground, but believe it or not we know we have to work. We’re aware of the importance of putting a lot into our work – our first job especially. Besides, I’m sure we do so more than some others: forget about the clichés.” INTER. 08

Accordingly, they generally express deep respect for their superiors, not for their hierarchical position but for their skills and expertise; attachment to the manager and respect for the hierarchy develop on these bases.

“You know a line-manager is important but for me he has to be competent and then I’ll respect him. I do not see why I shouldn’t ask him for an explanation and point out my disagreement. The relationship should be two-way.” INTER.16

Thus, it is not rare to observe that this generation can openly and directly express its criticisms of line-management. It will obey the more easily if it considers the decision just and relevant. So it is thought that this generation’s respect for their hierarchy is not a given but acquired throughout their experience in the enterprise in so far as it allows them to consider this hierarchy is legitimate.

“I just wait and see – of course he’s my superior but I’ll recognize him as such when I’ve seen him at work. If he’s competent I’ll obey him.” INTER.13

1.4. The Social and Managerial Issues

Various issues arise in the light of the questions expressed and are connected to the enterprises’ HRM systems. Thus, the questions of recruiting and attractiveness are still essential but those relating to career management, training policies or again remuneration are also present. These points confirm the results of surveys such as those by CEGOS (2009) and APEC (2009: 26): “the anticipation of professional or geographic mobility by young graduates and under 30 managers entails less emotional commitment to the enterprise”.

Faced with the recruiting problems many enterprises encounter, it becomes essential to favor new communication and information methods aimed at this generation and oriented towards the ICTs. Thalès’ experience gives pride of place to issues of diversity that are most important for this new generation:

“Our project consists of convoking managers and HRs to raise their awareness to the anti-discrimination rules and the risks of “cloning” due to narrow recruiting sources (about 15 colleges in France). Talking about career and origins diversity has enabled us to draw their attention to the importance of recruiting skills and not just qualifications from one college rather than another. We have trained each of our managers and both internally and externally the effect has been important for creating a link.” Vincent Mattéi, Head of Recruitment Sourcingvii.

vii Intervention during a round-table at the 6ths Journées internationales de la diversité of Corté on 30 September 2010.

This example shows that enterprises use themes when they communicate so as to give prominence to values matching what the individuals of this generation are looking for.

The traditional recruiting tools have proved to be rather ineffective and the arrival of human resources platforms, blogs, and employee forums is becoming one of the key factors for attracting and recruiting this generation. To attract these potential candidates and new talents and keep them loyal are two objectives that lead to favoring new ways of recruiting. Using information and communication technologies has become one of the key factors in these recruiting practices (recruiting via the web, social networks, etc.). To attract them the recruiter must give a precise job description: explain what is expected in terms of activities and missions, whom they are going to work with, and the consequences flowing from their career development. The objectives and values this generation looks for require the development of collaborative interfaces that can, for example, be useful to organizations. They are potent tools that are capable of giving a precise idea of how the professions work and how it is perceived they evolve, and of the social climate inside the organizations. The employer’s capacity to be attractive will be enhanced by transcending thought on qualifications, positions or jobs; in this way, a more attractive approach to the professions must be favored.

More globally, attractiveness is also reinforced by all the actions undertaken to improve the enterprises’ image with this generation. These various communication actions are, thus, designed to transmit values corresponding to those sought by this generation but they also develop more modern management tools and practices.

2. Management Tools and Practices: towards More “E”

Present-day research in managerial sciences shows that management must evolve towards a new style (2.1) inducing the adoption of new management tools (2.2).

2.1. Towards the Search for a New Style of Management

2.1.1. Towards More Meaning

The style of management that favorizes autonomy and taking initiatives can give new entrants a proactive attitude (Lacaze, 2005). On this subject, in academic circles, the emergence in management sciences can be observed of a new managerial tendency that favors benevolent intra-organizational management responding to the expectations expressed by employees of every generation. This element is interesting in so far as it matches the aspirations of generation Y concerning the desire to integrate with and trust colleagues and the enterprise.

“For me the enterprise is like in my personal life, I must establish reliable relationships and I have to be able to trust the others and have others trust me.” INTER.21

“The links you make in professional life are important as they allow conviviality and favor a better atmosphere.” INTER.20

The members of the generation Y need to have a global vision of the enterprise’s personalities and processes or management systems as understood by De Vaujany (2006): “who are the other employees?”, “what do they do?”, what are the management processes in the enterprises, etc. All these questions are formulated so as to know and be able to judge by oneself whom to address and with what processes and tools. This point accords with what this generation looks for: autonomy and being treated as responsible. To do this, it is necessary to have a thorough knowledge of the organization – of its key figures and how it works.

Thus, this search for meaning through a better grasp of information – a search for trust and social connections – is sought by this generation, and the style of management must take an interest in it.

2.1.2. Towards Managing the Individual/Collective Paradox

Generation Y puts a lot into group projects to develop its skills and bring change to the enterprise. It wishes to devote time to achieving objectives fixed autonomously and with certain responsibilities. But it does not lose sight of another objective – having enough free time for itself. Generation Y’s work-style gives pride of place to the project mode. One of the motivations for team work lies in the fact that a Y gives great importance to being able to learn constantly, which can materialize during project group exchanges. The generation wishes to take part in projects to develop new skills. As a result this generation no longer has a job for life outlook like generation X but rather:

“I’ll leave my firm when I think I have done or contributed all I can or because I’m no longer learning anything”. INTER.06

If it is accepted that managing young generation Y people is rather difficult, then it is because they are more receptive to change; in fact, they seek it as a stimulant for their professional life. Used to a changing world they are on the look rather for constant learning, and offering varied training to a Y is a way of meeting his expectations. Thus, compared to previous generations these individuals are characterized as a generation that consumes training; training is, therefore, perceived as a “real everyday consumption product” for these internal customers.

This generation is also very demanding when it comes to career progress and quality of working life, and does not hesitate to have multiple professional experiences to acquire new skills and broaden its network. In the same way, it will be advisable to offer them the chance to look about and make a career move at the European or international level. For this generation, mobility is a vital need.

Members of generation Y often demand a management adapted to each of them; for department heads this means knowing each of their subordinates, taking the time to become acquainted with the culture, values, and personality of each one so as to be sure of a high level of performance. This often involves a more personalized management style.

“Giving value to personal skills and adaptability are part and parcel of good team work. Individualism in such a case is not seen as selfishly damaging to the team of co-workers” (APEC, 2009: 27).

2.1.3. Towards a Recognition of Generation Y’s Commitment

It should be noted that the generation of under 30 managers arrived on the jobs market after the 35-hour week law was passed (APEC, 2009). Training is central to the systems for integrating young people (Charles-Pauvers, Peyrat-Guillard, 2005).

This generation is often seen as less committed or less motivated by work. But looking at things differently means accepting the idea this generation is motivated in another way. Of course, seeking a balance between private and professional life is important and explains the sacrifices they can make in earning less, but this implies that the sacrifice is compensated for by an interesting extra-professional activity. Thus, those who think they are less committed are mistaken. The generation is looking for a more flexible organization of their working time and timetable. Working in a framework of fixed hours is considered a constraint. The relation they make between work and free time is calculated so as to profit all parties:

“I’m ready to work a lot but that way I also know I’ll have more time free. It’s quid pro quo.” NTER.19

2.1.4. Towards Inter-Generational Management

Managing generation Y imposes inter-generational management on enterprises. Both generations X and Y are in the enterprises – a point that begs the question of managing the seniors. Thus, the issues managers face tend to be how to prevent conflicts that may arise between generations and the feelings of unfair treatment that may be perceived between these generations.Therefore, management systems must be oriented towards managing knowledge and especially the issues connected to its transmission. Mentorial or tutorial practices will enable enterprises to assure the connections between these generations. Preparing new managerial behavior is becoming important. This explains why certain enterprises develop mentorial and tutorial practices so as to reconcile these generations and create a social bond between them; especially when baby boomers or Xs are called upon for this type of activity (Hulin, 2010).

2.2. New Management Tools to Favor

2.2.1. Tools for Attracting and Recruiting

The enterprise needs to rethink and renew its means of communication to be more attractive. The traditional tools have proved to be ineffective and the arrival of human resources platforms, blogs and employee forums are possible responses (speed-dating, etc.).

“All the macro-demographic data show a problem in recruiting engineers and business school students. Young people will have the whip hand tomorrow! I’m convinced this generation Y will give an unequaled performance level to the businesses that know how to make the most of their potential: optimism, resilience, international outlook, passion for communication, and the Internet are positive values these young people transmit. On the other hand it is difficult to force models on them we can’t justify.” François de Wazières, International Recruitment Department, L’Oréal viii .

viii http://lagenerationy.com/2009/03/21/la-generation-y-vue-par-les-drh/.

Certain enterprises, currently, put their energy and communication action not into recruiting tools but into working on the image of their enterprise to make it more attractive and, sometimes, their employees more loyal. Let’s take the example of FON. In this enterprise, the action taken is based on the relation generation Y has with the DSNs. Acting on the premise that this relation can be used to enhance the power and image of the enterprise, a double effect is expected:

- The first is internal to motivate and keep loyal the enterprise’s internal customers – its employees;

- The second is external and acts on the attractive effect these types of actions can have on potential generation Y candidates and naturally on potential consumers of the enterprise’s products and services.

This enterprise’s concept is based on an approach that relies on sharing the network and not charging for it – two values intrinsically linked to Web2.0 that young people understand very well (Leroy, 2008). FON’s aim is to make Wifi accessible all over the world and above all for free. To do this, the company relies on experience pooling and co-creation. In fact, any cybernaut on the planet can become a “fonero” by subscribing and adding a FON router to his provider’s box. In this way, he offers free access via his line to all the other foneros who also undertake to share their connection. Many cybernauts have subscribed to this concept, thereby, creating the biggest free world web access network. It should be noted that the foneros are not paid for this service of sharing their connection; they pay their conventional subscription to their access provider with no reduction and have to buy the router to connect to their box at their own expense.

This co-creation of services is an unprecedented lever for the enterprise; its impact, however, on internal management must not be minimized. Co-creation marks a new stage in managing relations between the enterprise and consumers as much as between the enterprise and its employees. It requires the organization to be rethought as a whole; the consumer can intervene at any moment and in any way in the process of creating the offer. In the same way, Y employees can see in this experience the respect they seek: innovation and creativity, change, the will to become members of a community while individually contributing something to the system, the feeling they are useful to others, etc.

Furthermore, the case of Fon shows the importance of cybernauts’ adhesion to the values the company promotes, although the enterprise has no means of communicating its values formally to the participants. Still other, however, human resources problems present themselves to managers: how to ensure the enterprise’s values are adhered to; how to maintain the quality of service where the strength of the distribution network (in this case precisely, more than two million web accesses) depends uniquely on the goodwill of cybernauts who do not know one another; who must be deemed to be employees in such an enterprise with such open and enlarged frontiers? knowing the foneros are not really employees of Fon while being collaborators indispensable for the functioning of the network. Lastly, the extension of the network depends enormously on the co-optation of the foneros who become Fon’s emissaries. This example also shows the difficulty in understanding certain human resources policies such as training in this type of enterprise. The community of foneros proposes high-level tutorials and FAQ to help newcomers and this internal training – based on pooled experiences and transmission – is not the responsibility of the enterprise and depends on the goodwill of more or less external volunteers. This, therefore, begs the question of HRM and of what is the responsibility of a single enterprise or of several, or of a territory or of a sector.

2.2.2. Tools for loyalty and Motivation

A large majority of generation Y individuals do not foresee passing their whole career in a single enterprise. Paradoxically, for the Ys a career move generally means a change of position but not necessarily a change in responsibilities. In order to gain these employees’ loyalty, giving them an idea of the positions they could obtain might limit how many actually leave.

Career management systems must take into account this generation’s profiles, which are marked by a desire for balance between personal and professional life: “there is a real problem in making new recruits loyal to their employer. Among the classic and general HRM tools two levers have seemed most promising to me: giving real responsibilities and offering proper professional careers” (Rose, 2006: 14).

In organizational terms the members of this generation ask for flexible hours which corresponds to their wish for a balance between work and private life. They desire to benefit from a maximum of flexibility in the organization of their work: hours, in-house training, sabbaticals, family leave, solidarity leave, work place crèche. The contribution made by each can be observed outside the enterprise and the enterprises must take this into account in what they do. For example, possibilities will develop offering employees the chance to contribute to and participate in social or environmental activities for charities for instance. Pralong (2009) affirms that to succeed in integrating them and keeping them loyal “a new deal” is needed “between employees and enterprise”. For this, he “first proposes to remember the relationship between employee and enterprise is dissymmetrical. The least influential (the employee) cannot be expected to be the most trusting party in the relationship. So it’s up to the enterprises to make the first steps to restore trust. What could these steps be? […] simply to make some commitments, albeit modest, and respect them. This should be possible.”.

Thus, if generation X gave a greater place to its professional life, this is not the case of generation Y. This generation gives first place to its professional life but, for example, is not ready to do overtime. So from an HR point of view these data have to be born in mind. A human resources director must succeed in taking measures allowing his employees to reconcile their professional with their private lives. This finding is reinforced when it is realized that the individuals of generation Y, who already give great importance to their private life today, will give a still greater priority in 15 years. These perspectives must be taken into account in managing these people’s careers. For example, enterprises offering their employees services such as crèches or dry-cleaning help stop them from being overcome by their personal life.

Conclusion

Research studies on juniors and seniors are more and more frequent but, on the other hand, the intergenerational aspect is little developed (Cartigny, 2006). That is why this article and study has endeavored to show not a systematic opposition between generations within the enterprise or to stigmatize different generations but rather some elements for adapting management systems that will facilitate links between the generations and improve the management of this generation Y.

Through mobilizing people from different generations and with tools better adapted for digital use or to these generations’ values these systems will be more responsive to the needs and expectations generation Y expresses. Thus, the issues involved in recruiting and being attractive, in winning loyalty and motivation are at the heart of the concerns of enterprises and the paths envisaged today mark the renewal of practices in human resources.

In any case, this article cannot reject the idea of such an endeavor’s relevance: does generation Y really exist? Some would answer in the negative such as Pralong (2009: 18) “Our results imply it doesn’t. They show that the influence of belonging to a generation is less than that of belonging to the group of managers. The effect of socialization is stronger than that of being part of a generation”. Others attempt to show that if the values sought are identical, how they are expressed is not, which makes a renewal of the systems necessary. It was in this latter perspective that this study was written.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

References

APEC (2009). “La Génération Y dans ses Relations au Travail et à l’Entreprise,” Les Études de l’Emploi Cadre, décembre.

Publisher

Bourhis, A. (2006). “Les Défis de la Gestion Intergénérationnelle,” Conférence présentée dans le cadre du rendez vous technologique Montégérien.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Bourliataux-Lajoinie, S. (2007). “Le Web, le Consommateur et la Publicité ,” Economie et Management, n°124, p. 4-14

Publisher

Cardon, D. (2008). ‘Réseaux Sociaux de l’Internet,’ Réseaux, volume 26, n°152.

Google Scholar

Cartigny, L. (2006). ‘La Dynamique Intergénérationnelle au sein des Organizations,’ XVIIème Congrès de l’AGRH, Reims.

Chaminade, B. (2007). ‘Comprendre et Manager la Génération Y,’ Journal du Net.

De Vaujany, F.-X. (2006). “Pour une Théorie de l’Appropriation des Outils de Gestion : vers un Dépassement de l’Opposition Conception-usage,” Revue management et avenir, vol.3, n°9, p. 109-126.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Hulin, A. (2010). Les Pratiques de Transmission du Métier : de l’Individu au Collectif. Une Application au Compagnonnage, Doctorat de l’Université de Tours.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Jacob, R. & Harvey, S. (2005). ‘La Gestion des Connaissances et le Transfert Intergénérationnel : une étude de Cas au Sein de la Fonction Publique Québécoise,’ Télescope, revue d’analyse comparée en administration publique, 12 (2). p. 12-25.

Google Scholar

Lacaze, D. (2009). “Pour une Gestion des âges Synergique : Décryptage d’un Conflit de Génération Chez Thalès,” XXème congrès de l’AGRH, Toulouse.

Google Scholar

Laize, C. & Pougnet, S. (2007). ‘Un Modèle de Développement des Compétences Sociales et Relationnelles des Jeunes d’aujourd’hui et Managers de Demain,’ XVIIIème congrès de l’AGRH, Fribourg.

Leroy, J. (2008). ‘Gestion de la Relation avec une Communauté Virtuelle dans une Stratégie de Co-Création : les Leçons du cas Fon.com,’ Décision Marketing, n°52.

Google Scholar

Pralong, J. (2009). “La ‘Génération Y’ au Travail : un Péril Jeune ?,” XXème congrès de l’AGRH, Toulouse.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Prensky, M. (2001). “Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants,” On the Horizon, NCB University Press, vol. 9, n°5, octobre.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Rose, J. (2006). “Les Jeunes et l’Entreprise. Comment (re)construire la confiance ?,” Personnel, n°474, p. 1 4.

Vincent, C. (2010). “L’avenir est aux Entreprises Y ,” Enjeux Les Echos, p. 25-28.

Publisher