Introduction

The embodiment of a product and/or service in the right person has become a challenge for publicity designers. Several questions arise in this regard. Is it by the use of attractive celebrities that advertisers can meet the expectations of an audience in search of fun and excitement? Is it by reference to credible people that we can protect helpless consumers, lost in the accumulation of information? Is it the congruence between the medium (model) and the product that enhances the proximity between the medium and the audience?

These questions were the subject of several academic researches (Kahle et al (1985)), which have focused on the study of celebrities’ attractiveness and its impact on the emergence of a favorable attitude towards products or brands. Devebec et al (1984) and Friedman et al (1979) show that the change in belief and attitude is possible with an attractive person.

Nevertheless, these assumptions have aroused sharp criticism insofar as the effect of involvement is neutralized. Actually, studies have shown that these icons of grace and beauty, the spokesmen of seduction, lose their influential power when they represent non-cosmetic products (Kamins (1990) ; Till et al (2000)) or products with high involvement (Petty et al (1981)). Thus, we can no longer state the effect of an attractive celebrity with consumers who are guided by reason and who give great importance to the information content of the product to the detriment of its shape.

According to the results of these researches, we note that debate persists about the incarnation of the product and / or service in a celebrity.

We assume, in this regard, that the use of an “ordinary” woman model could overcome limitations raised against celebrities.

So, the main question of the research is:

“What’s the image of an “ordinary” woman as perceived by men and women?”

Research Methodology

In a first part, we have referred to exploratory research to infer the assertions. That’s why we have opted for the qualitative semi-structured individual interview conducted with 30. This type of interview allows us to strengthen the spontaneity of the interviewees and to enhance the opulence of information as well as to explore this field, unknown until now (Vandercammen et al (1999)). The interview guide discusses several topics in the form of open questions such as the physiological characteristics of an “ordinary woman” (beauty, charm, seduction, silhouette), the intrinsic characteristics (needs, personality, motivation) and the extrinsic characteristics (culture, family, friends, colleagues).

Concerning the tool employed, we have referred to semantic software (Tropes) for analyzing and coding what was said by the interviewees. The advantage of this software is the ability to quantify the data to measure situations and to visualize the relationships between the references in a detailed or overall way.

In a second part, in order to determine the salient features of an ‘ordinary’ woman, we have referred to KERNEL as a method using dominance as an instrument for collecting information from 30 people. Designed by Serge Rebeillard and Cecile Kreweras, KERNEL recognizes the achievements of Roger Sperry (1913-1995). Indeed, the approach aims to place the interviewee in terms of its emphasis on natural behavior from each hemisphere. Each participant will conduct in this sense a self-positioning according to preferences and predispositions. Rebeillard et al (2006)

Procedure of Analysis of Dominance (AD)

AD is a procedure to direct prioritization using the artefact of the Plateau of Dominance also called “play mat”. It allows the understanding and the explanation of a phenomenon involving many opinions and conflicting preferences.

From the beginning of the exercise, each participant has 60 suggestions which he is supposed to rank on the board. We have obtained these propositions from the first exploratory research using Tropes software.

The propositions to prioritize, are in the form of cards and each participant is asked to classify these cards on an area of 100 silent square spread on four quadrants labeled “I don’t agree that the statement corresponds to the ordinary woman,” “I more or less agree that the statement corresponds to the ordinary woman, “” I agree that the statement corresponds to the ordinary woman “and” I fully agree that statement corresponds to the ordinary woman.”

The packet of cards is shuffled in each exercise before ranking on the board, so we avoid the effect of list of a questionnaire. Unlike other methods, we notice that the interviewee is more involved in the method because he/she is required to read the items many times before each ranking and his responses will be more refined in this case.

Results of the First Exploratory Study

To determine the profile of an “ordinary” woman, we opted for exploratory research using interviews as a tool to gather data and Tropes as software to process information.

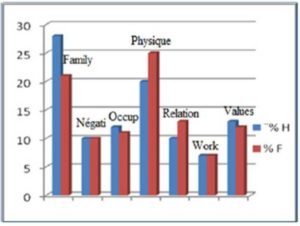

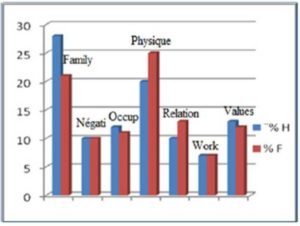

A first reading of the interviews suggests the existence of two types for the Tunisian woman: traditional versus modern. The first graph shows that men place more the “ordinary woman” in her home environment (including themselves as husbands), whereas, women refer to physiological characteristics and to relationship to describe the “ordinary woman”. (See Graph1)

Graph 1 : Percentage Difference between Men and Women

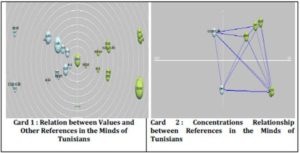

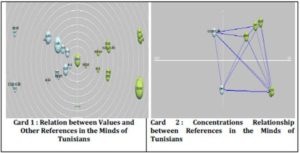

In order to compare the perceptions of men and women regarding the profile of an “ordinary” woman, we have referred to card 2 and card 3.

We remark that women describe the “ordinary woman” through her intelligence, her ambition, her work and her values. Thus, the image of the “ordinary woman” is an “ambitious” woman, “smart” that seeks to express herself through her work while respecting the main values of the society. (See Card 2)

As for the Tunisian men, beside useful occupations, values seem to be acting (to other references). They also occupy the same place, but with a more masculine vision with the emergence of the husband’s strong role as a real “household head”, which is much less noticeable with women. (See Card 3)

Results of the Second Exploratory Study

In order to refine the profile of an «ordinary» woman and identify her salient features, we used KERNEL as a method to analyze and dominance as a tool to collect information.

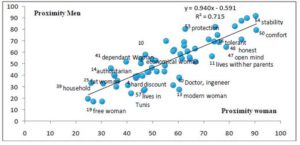

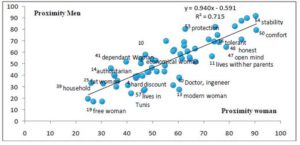

Card 3 : Comparison between Men and Women Regarding the Image of an « Ordinary » Woman

According to card 3, we observe that men place stability and protection on the top of values of an “ordinary” woman (OW) while women situated comfort on the top of the aims of the OW.

For men, the OW may be identified in the woman who prefers fresh products to frozen ones. However, for women, the OW is the symbol of the honest woman and tolerant mother who forgives the mistakes of her kids.

This card also displays the image of the Non “Ordinary” Woman (NOW). For men, this is the mother who opts for an authoritarian leadership style with her children. Besides, OW is seen as a dependant woman who always needs a coaching in her work.

For women, the modern and liberated woman doesn’t represent the OW. Moreover, functions like doctors, engineers which demand a developed know-how surpass competences of the OW.

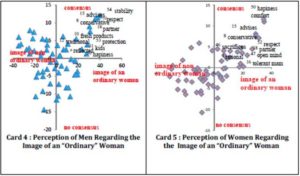

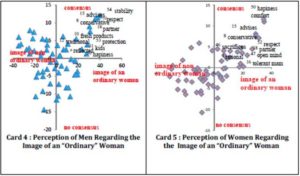

According to the two cards (4 and 5), women and men share the same opinions regarding the image of the OW. We observe a strong consensus on the stability, comfort and family protection as essential goals in the life of the OW. It is the same for the role of the woman in her home. She is actually the mother who takes care of her children’s education who is the main preoccupation in her life.

Physically, we note an agreement of opinions regarding the beauty of the OW; however, we note that women rather than men rely on the natural “applying little make-up bit”.

With regard to psycho cultural characteristics, we see that men associate the image of conservative and traditional woman to the OW. They believe she is the woman that we meet every day in the souks and in supermarkets.

As for women, they regard her as the honest woman who seeks to share responsibilities in her home. She’s the competent open-minded woman, with an open mind, looking for independence through her work.

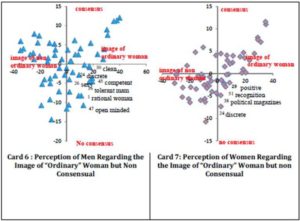

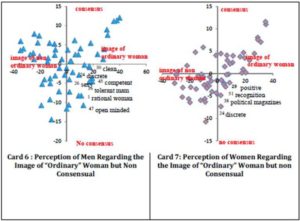

When referring to card 6 and card 7, we identify an image that has raised a lot of controversies between men and women about the image of the OW.

For some men, the OW doesn’t symbolize the openness and competence, neither the rational woman in her purchases. For women, the OW doesn’t represent the woman who gathers information from political and intellectual magazines or who seeks for social recognition.

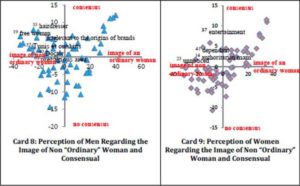

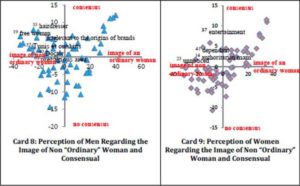

We identify through card 8 and card 9 the characteristics of a woman far from being an OW. According to men, it seems that the free woman who can live by herself in her home and the modern woman who travels alone are not considered as OW. In addition, the woman who spends her time between hairdressers and beauticians doesn’t represent the OW.

According to these outcomes, we confirm the results of the first qualitative study that men see no relation between OW and professional ambitions. In this regard, OW is far from being seen as a doctor, lawyer or an engineer.

AS for women, their opinions converge regarding the characteristics of “Non Ordinary Woman”. They think that the image of authoritarian mother and the woman who enjoys entertaining programs and games are two rejected images of the representation of an OW.

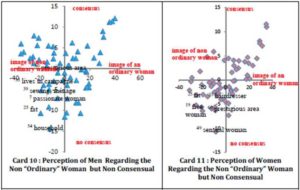

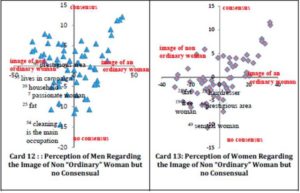

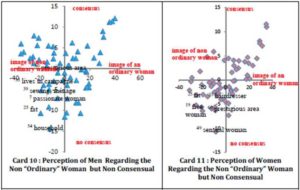

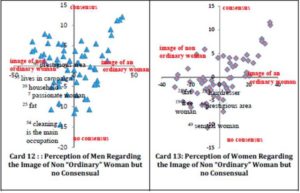

According to card 10 and card 11, we note a consensus between men and women concerning the image of the OW. In fact, the OW is far from being a free woman who can live alone.

We also note a convergence of views between men and women in terms of concerns. Indeed, the Tunisian see that the woman who attaches great importance to her physical beauty is far from the image of the OW.

Conclusion

After a qualitative investigation, we identified the prominent salient features of “ordinary woman” as seen by men and women.

If we wish to draw the physical portrait of an OW lucidly, we infer the image of natural women moderately beautiful. Like the majority of Tunisian women, she cares about her line, her beauty but not in an exaggerated way.

The image of a physically attractive woman, sexy and sensual is considered by some participants as a stereotype, away from the image of an OW.

The results also show that there’s no consensus regarding the clothing style of the OW. For some, OW is seen as someone who dresses in a discreet way. For others the woman who dresses modestly is similarly away from the image of OW.

Relating to psycho cultural characteristics, we deduce that children are a predilection for the OW to the detriment of the household and shopping. She is the woman who advocates honesty, stability, protection and self-respect.

Work is a springboard for the OW’s independence and self-esteem. Through her salary, she can pay charges (hair stylist, care …) and cover some expenses of her household. She wants to establish there by the image of a partner woman, a spouse and not the submissive woman who executes her husband’s without objecting.

The competence of an OW is a polemical topic since some see in the OW, the competent woman while others refuse this image. They don’t believe in the ability of OW to manage and lead her colleagues. They believe that this woman is deprived of career ambitions.

On the cognitive level, we observe a consensus in terms of need for cognition. Men consider OW as a rational person whereas men consider her a thoughtful person. In both concepts (rational and thoughtful), we identify the need for information before purchasing a product.

Calling to “ordinary” women would be more efficient than using celebrities whose price doesn’t cease climbing, which could prevent the proper management in times of crisis. We also suggest building a model of advertising persuasion in the case of an “ordinary woman”.

No study is exempted of limitations. In fact, we limited ourselves to the analysis and interpretation of information from interviewees. We recommend, in this context, to use projective tests as a technique for gathering information (the Chinese portrait, role play …).

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

References

Andreani, J. C. & Conchon, F. (2005). ‘Les Méthodes d’analyse et d’interprétation des Études Qualitatives :Un Etat de l’art en Marketing,’ Congrès des Tendances du Marketing, Venise, 1-26.

Google Scholar

Friedman, H. H. & Friedman, L. (1979). ‘Endorser Effectiveness By Product Type,’ Journal of Advertising Research, 19 (5).

Google Scholar

Kahle, L. R. & Homer P. M. (1985). “Physical Attractiveness of the Celebrity Endorser: A Social Adaptation Perspective,” Journal of Consumer Research, 11 (4), 954-961.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Kamins, M. A. (1990). “An Investigation into the Match-Up Hypothesis in Celebrity Advertising: When beauty may be only skin deep,” Journal of Advertising, 19 (1), 4-13.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Petty, R. E., Cacioppo, J. T. & Schumann, D. (1983). “Central and Peripheral Routes to Advertising Effectiveness: The Moderating Role of Involvement,” Journal of Consumer Research, (10), Septembre.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Radu, M. (2004). “De la Comparaison Sociale à l’intention Comportementale. Les publicités pour produits cosmétiques amincissantes,” questions de communication, 5, 103-114.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Radu, M. (2006). “La Comparaison Sociale avec les Femmes Mannequins : Un Face à Face Stimulant ou Dangereux ?,” Marketing et communication, 1, 56-70.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Solomon, M. (2005). ‘Comportement du Consommateur,’ 6 édition, Pearson Education.

Google Scholar

Till, B. D. & Busler, M. (2000). “The Match-up Hypothesis: Physical Attractiveness, Expertise, and the Role of Fit on Brand Attitude, Purchase Intent and Brand Beliefs,” Journal of Advertising, 29 (3), 1-13.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Vandercammen, M. & Gauthy-Sinéchal, M. (1999). Recherche Marketing Outil Fondamental du Marketing, De Boeck & Larcier, s.a, Paris, Bruxelles.

Publisher