Introduction

There has been a great deal of alarming concern in recent decades regarding the danger of minority cultures in the world being swamped by dominant cultures, in particular those from English speaking countries such as the USA. Hampton (2004) acknowledges this while stressing that the vehicle for a global information highway is content. Consequently, minority cultures should preserve their own country’s local content as the platform of cultural diversity no matter how much they are influenced by the dominant cultures. This concern has been highlighted, in the UNESCO (2001) Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity, Article 4, about human rights as the guarantor of cultural diversity:

“The defense of cultural diversity is an ethical imperative, inseparable from the respect for human dignity. It implies a commitment to human rights and fundamental freedoms, in particular the rights of persons belonging to minorities and those of indigenous peoples. No one may invoke cultural diversity to infringe upon human rights guaranteed by international law, nor to limit their scope”.

This applies to a small country like Malaysia, which boasts of a multicultural society with many characteristic forms of cultural expression. The Communication and Multimedia Act 1998 (2010) identifies one of its key objectives as being the need “to grow and nurture content as ‘cultural representation’ that facilitates the national identity and global diversity”.

In addition, the urge to protect cultural diversity is also associated with new media practices (UNESCO, 2010). Despite the almost universal adoption of mobile phones in Malaysia, there is only limited local cultural content in comparison to the content from overseas. The former Minister of Energy, Water and Communication has stressed the growing importance of content-based services since “people do not subscribe to telecommunication services just to talk” but increasingly make use of content-based services (Lim, 2005). Minister Lim (2005) went so far as to say “Content is King”. The Information, Communication and Culture Minister Datuk Seri Dr Rais Yatim (2010), in his speech reported in The Star, has called for more cultural content for mobile phones. This could stimulate the minds of Malaysians in an era of sophistication and borderless communication. Roslan (2007), as cited in Norshuhada and Syamsul (2010), states that this content needs to focus on the areas of education and learning, entertainment and games. In the field of learning, one aim is to increase learner’s access to information by distributing it via mobile local content and making it widely obtainable and accessible (Quinn, 2011).

This article explores the mobile content issues through interviews with Malaysia’s mobile technology experts. The aim is to initiate ideas and to find out the emerging themes regarding the availability of mobile phone content which reflects Malaysian culture.

The organization of this article will begin with the methodology of how the interviews were conducted. Secondly, the main findings from the interviews are presented. Thirdly, issues are discussed and some recommendations regarding mobile cultural content are made. It is hoped that this paper will contribute to the understanding of the importance of Malay content for mobile devices. As it is, this topic is under-researched and, while there has been some quantitative exploration carried out (Ismail, Idrus, & Ziden, 2010; Karim et al., 2009; Mahamad, Ibrahim & Taib, 2010), there has been very little qualitative research regarding this. The interviews presented in this paper provide a greater depth of understanding than those previously presented in the literature.

Methodology

Six interviews were conducted from a range of industry experts from various areas of the mobile sector. All interviewees were located in the Klang Valley and Cyberjaya areas, where the mobile industry is largely situated. The experts were identified by a number of defining factors, for example their roles in the industry, their affiliations with both industry and government bodies, their experiences and lastly their contributions to the development and sustainability of the mobile industry. The interviewees are: the Deputy Managing Director of the Government’s Technology of Education Department; Deputy Director of Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission; Director of a mobile games software company; Director of a mobile learning company; Executive Director to a Malay and Islamic local content company; and Senior Executive of a multimedia development corporation.

The interviews were semi-structured with questions about local content in current and past projects that the interviewees had been involved with, and their views on the challenges and opportunities for the gradual increase of local content in the future in order for it to reach acceptable levels. The duration for each interview ranged from 30 to 40 minutes and notes were taken at the time of the interview. From the notes, themes were identified and grouped into various categories.

Examples of the questions include, “What motivates people as users of mobile applications?”, “Which mobile applications are more popular nowadays?”, “Which mobile application software has cultural content?”, “What are the challenges in the mobile content and mobile application industry?”, and “What are the government’s initiatives for the mobile application industry?”. The answers to these questions will draw attention to the main issues regarding activities and progress in the Malaysian mobile content industry.

Findings from Interviews

The interviews reveal themes which can be separated into two groups: firstly, the categories of mobile content and, secondly, challenges to the mobile content industry.

Categories of Content

The interviews showed that mobile content in Malaysia is lacking in variety, especially in the local cultural content area. Also, current activity is more focused on making commercial profits by targeting the wider public while neglecting the local “flavor”. However, an effort has been shown by the Malaysian government to promote content development at a higher level, through collaborations between university students and industry partners.

a. Islamic Content

In Malaysia, Islam is the national religion. One of the key issues that was highlighted by the Executive Director of the local content company is the proliferation of Islamic content and practices via Short Message Service (SMS) and Multimedia Messaging Services (MMS). In addition, there have been award-winning applications such as the Muslim Diary for the Islamic community. This type of religious content being sent to mobile phone subscribers reinforces Islamic practices such as prayers and the Hajj, and is of benefit to the Muslim-Malay community. The Executive Director stresses the importance that Islamic religious and cultural influences play in the delivery of mobile technology content. In particular, this mobile content is important during and after Ramadan, the “fasting month”, when there is a greater volume of Islamic content via SMS and MMS delivering messages of coming events. In response to the higher volume of mobile content during Ramadan, the company has created “Aidil Fitri greeting cards” for the Muslims’ celebration, which can be downloaded and distributed to other subscribers via MMS. The use of “push” technologies allows MMS to be sent more quickly to larger volumes of subscribers.

b. Children’s and Adult Literature

One of the interviewees is currently working on an e-mobile book based on children’s stories and adult literature. Part of this project is the development of a mobile content engine to translate the MMS content (image, text and voice) to the Malay language.

c. Jawi Writing

A mobile games software company uses the Jawi Translator, a program that teaches students the “Jawi” writing style. According to Maskhuri et al. (2001), evidence of the Jawi script was found on a tombstone dated 1303 AD in the Malaysian state of Terengganu. Jawi is the Malay writing script based on the Arabic script, with extra characters to accommodate Malay vocal sounds.

d. Games Content

Another interviewee suggested that good games content should have a concept of sharing and collaboration⎼ add moral values, for example “respect your elders” or “courtesy”; and that games should be fun. The games content is sometimes embedded with a learning activity.

Challenges with Mobile Content

a. Lack of Standardization of Mobile Phones

One of the interviewees spoke of the need to use specific measurements in the layout design of mobile greeting cards so that they fit the screen of mobile phones. One of the significant disadvantages that she pointed out was the number of mobile phones models available in Malaysia, all with varying screen requirements and screen sizes. She voiced the need to test all the Nokia models of phone, the most common brand in Malaysia, for compatibility with the mobile application software in order to know whether the application can be used. Furthermore, limitations to the number of text messages that can be sent limit the potential of the mobile phone. The application also needs to cater for the size of the phone memory in order to run successfully, and this varies from one phone to another.

b. Small Malaysian Market

Attention was drawn by one of the interviewed Directors to the fact that products that use Malaysian cultural content are not as “saleable” on either the local or international markets. The lack of international interest, which has severely restricted sales, is seen as the result of Malaysian mobile content not having been converted to other languages. The interviewee pointed out that a major shift in the way that consumers view such products needs to be achieved.

c. Insufficient Profit Sharing

One interviewee identified “the need for a greater local content that is commensurate with a greater acknowledgement of development funding and increased profit sharing of the market proceeds”. Currently, telcos receive equal shares of the profits, thus reducing profits to the content producer. However, this arrangement “does not reflect the true value of the local content provider, which should be technical know-how and an intellectual property”. This is an important issue that needs to be addressed and resolved in order for the industry to move forward.

d. Lack of Training for Mobile Content Developers

As part of the development of local content, one interviewee pointed out that “there was a need for more continuous training” for local content producers. Currently, the numbers of local developers, especially for Androids and iPhones, are still small because some companies still rely on overseas talent from India and elsewhere.

e. Stakeholders’ Mindset in the Education Sector

The Director of the Mobile Learning Company mentioned the need to change the mindset of parents and teachers to encourage their children’s learning via mobile phones with their parents’ supervision and teachers’ monitoring. Another interviewee, the Deputy Managing Director of the Technology of Education Department, expressed teachers’ concern on how mobile learning might not be suitable and can cause extra work for teachers. The paradigm of thinking necessitates change in order for this mobile technology to succeed.

f. Unawareness about Intellectual Property

Another issue raised was the neglect of software intellectual property. There is no point in applying for an intellectual property license when the software will phase out quickly, especially software which targets a smaller scale audience with smaller sales volume. Technology will change especially in the mobile industry. There will always be a better application to replace the earlier software. The cost of copyright will also introduce unnecessary burdens to companies.

g. Lack of Infrastructure in Rural Areas for Broadband Coverage

Current areas for broadband only cover big cities and towns in Malaysia, whereas the rural areas are unable to access broadband facilities. Mobile phone transmission is also out of reach in the rural areas. Therefore, mobile phone communication is a big issue in those areas.

h. Data Expenses

Current plans and charges of broadband data transmission via mobile phone are considered high, especially for an Asian country like Malaysia. Not everyone can afford to pay RM 80 ($30) or more per month for 5 GB of data, especially students and the people from rural areas with lower incomes.

i. Malaysian Cultural Regulations

The Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission, or SKMM, is the institution in charge of monitoring the content for local cultural sensitivity (SKMM Roles, 2010). In order to support SKMM, the Content Regulation Department was founded. The Content Forum is a body which has been designated to ensure content makers in Malaysia follow the rules laid down in the Content Code (SKMM Content Forum, 2004). Consequently, SKMM will refer to the Content Forum agency for regular updates pertaining to content policies and to ensure that Content Code procedures are followed.

j. Lack of Local Mobile Content

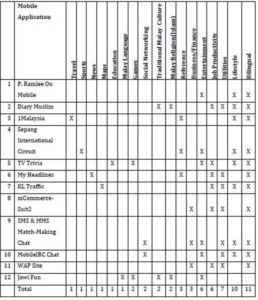

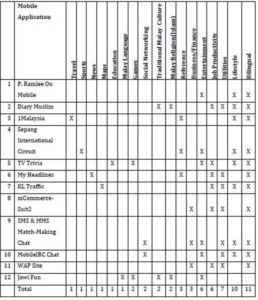

The number of mobile content applications produced by local developers is not as many as those contents from overseas. In addition, the value of the national identity is not reflected in the availability of mobile content in Malaysia. Also, the Multimedia Development Corporation MDEC Catalogue (2008) has been summarized; as Table 1 shows only twelve mobile applications created within the Malaysian context during that year of production.

Table1: Summary of Mobile Content Products with a Malaysian Context

Government Initiatives

There have been a number of interviewees who noted the importance of initiatives by the Malaysian Government to foster local cultural content.

a. Schemes to Foster Local Content

An aspect alluded to by one interviewee is the need to increase the quality of local content by providing more grants and money “in the hope that greater quantities of quality local content can be produced by local producers”. The interviewee stressed that there were many schemes initiated by the Government to foster local content: The Online Social and Community Content Creation Grant Scheme (ICONity); The Online Educational Grant Scheme (ICONedu); Technopreneur Pre-Seed Fund Program; Malaysia Animation Creative Content Co-Pro Fund; and Cradle Investment program (CIP ).

The citizens of Malaysia have benefited from the Multimedia Development Corporation (MDeC)’s program to facilitate the development of “technopreneurs”. One of the interviewees has managed to form a company from the Technopreneur Pre-Seed Fund Program. The concept of sharing mobile applications is a common cultural practice amongst Malaysian users. Malaysian people are very willing to share their applications like mobile games to other friends or colleagues who are keen to use the same application. Another interviewee, the Deputy Director of the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission, noted that the Local Content Development Policy Plan for the Nation or “Dasar Pembangunan Kandungan Negara” (DPKN) was still waiting for approval from Cabinet. This plan will enunciate all the necessary do’s and don’ts about local content for media, including mobile content.

b. Initiatives for Human Capital Development in Mobile Content

The interviews identified a number of issues with respect to human capital development and capacity building. In particular, it is recognized that training and career path planning and programs in the ICT industry need to be developed by the government in partnership with the higher education sector. In response to this concern, the government has implemented the Mobile Content Challenge competitions for institutions of higher learning. This competition was established in 2007 and had generated much greater interest in pursuing careers in ICT. Secondly, the competition provides an opportunity for students to network with industry players and government representatives. Equally important is the role that the mentor, as another aspect of the competition, plays in providing support and leadership qualities to students. This program has been extended to include secondary high schools, in the format of the “League of Creative Teams”. This is a national competition and currently there are ten finalists in the Mobile Games category for this year’s competition. This clearly demonstrates the level of creativity and the urge by youth to develop their own mobile games products.

Discussion

There have been good collaborations between the Malaysian Government and the telcos through student competitions and the technopreneur’s programmes. These programs acknowledge the importance of preserving national heritage and promoting local cultural expressions, as highlighted by the UNESCO Universal Declaration on Culture Diversity.

However, even though private companies from the industry have initiated a number of local content productions, there is still a lack of variety. After all, this new industry has not yet reached 5 years of age. Minister Lim (2005), as quoted previously, believes that “Content is King”, but this has yet to materialize. To engage young people, there has been an over-emphasis on games development at the expense of local content development. It is essential that schools engage students using more culturally appropriate mobile content. Moreover, there is a need to reconsider the banning of mobile phones at school and whether education could be enhanced by lifting the ban.

The limitations of Malaysian mobile content revealed by the interviewees demonstrate that much more still need to be done. For example, the need for more training opportunities and a good mobile infrastructure are evident. Qing (2010), reporting on broadband issues, doubts whether this will extend to country areas, despite the National Economic Model (NEAC 2010) affirmation of a new direction and initiative for broadband to be widespread in Malaysia.

Conclusion

This study, which delves into the area of mobile content, is novel because of its qualitative nature and its focus on interviewing mobile experts in different domains of expertise for the Malaysian context. The research acknowledges the contributions of the Malaysian government in motivating the development of mobile content. Similarly, the fact that the government of Malaysia has been supportive towards mobile content industries should be recognized.

Despite this, the variety of mobile content applications remains limited and there are demands for mobile content to be increased. New research into providing a variety of mobile content applications which have been locally designed could be done in the area of learning. Quinn (2011) highlights that mobile learning content can provide good solutions which are authentic to the local context. UNESCO (2009) has reported that the craft industry has been a source of income for developing countries, and so content which promotes knowledge surrounding Malaysian arts and crafts would be desirable. An example of local cultural content developed by Ariffin & Muthan (2008), “M-Tik”, is a mobile learning application which portrays an image of the national culture through Batik. Other areas of Malaysian content, such as information on food, natural resources, rituals and beliefs, songs, stories, dance, martial arts, the Malay language and history could also be made widely available via mobile content applications. In this way, the heritage of the Malaysian local culture will be preserved and revitalized, both locally and throughout the world.

This research has reached the conclusion that, as the mobile content technology emerges in Malaysia, the modern needs of university students should be considered and explored through this new field. Therefore, future research into this topic will include interviewees comprised of educators and students. To elaborate the findings from the interviews, observations of the classroom during the evaluation of mobile learning applications involving Malay content will be undertaken. It is believed that this future research will provide greater understanding in this area.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to express gratitude to all the experts who were willing to dedicate their time for the interviews. This appreciation also extends to the Ministry of Higher Learning of Malaysia, which has provided the financial support for the main author’s research study.

References

Ariffin, S. A. & Muthan, V. K. (2008). ‘MLearning Application Development in Malaysian Traditional Batik,’ MLearn 3rd Asia Pacific Conference, LTT Communication and Oum, Kuala Lumpur, 1-10.

Communication & Multimedia Act 1998 (2010). ‘Act 588,’ [Online],[Retrieved April 29, 2010], http://www.skmm.gov.my/link_file/the_law/NewAct/Act%20588/Act%20588/a0588s0003.htm.

Hampton, A. (2003). “A Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Information Highway,” [Online],[Retrieved August 15, 2010],http://portal.unesco.org/ci/en/files/14488/11607409751working-paper2-en.pdf/working-paper2-en.pdf.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Ismail, I., Idrus, R. M. & Ziden, AA. (2010). “Adoption of Mobile Learning among Distance Education Students in Universiti Sains Malaysia,” iJIM, 4(2), 24-28.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Karim, N. S. A.., Alias, R. A., Mokhtar, S. A. & Rahim, N. Z. A. (2009). “Mobile Phone Adoption and Appropriation in Malaysia and the Contribution of Age and Gender,” International Conference on Information and Multimedia Technology, IEEE, Jeju Island Korea, 485-490.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Lim, K. Y. (2005). ‘Minister Speech. The Telemanagement Forum’s Asean Regional Summit,’ [Online],[Retrieved August 15, 2010],

http://www.tmforum.org/WhyAttend/2719/home.html.

Mahamad, S., Ibrahim, M. N. & Taib, S. M. (2010). “M-Learning: A New Paradigm of Learning Mathematics in Malaysia,”International Journal of Computer Science & Information Technology, 2(4), 76-86.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Mashkuri, Y., Zainab, A. N., Rohana M. & Edzan N. N. (2001). ‘Digitisation of an Endangered Written Language: The Case of Jawi Script,’ the International Symposium on Languages in Cyberspace, Organized by the Korean National Commission for UNESCO, 26-27.

Google Scholar

MDEC Catalogue, (2008). Mobile Content & Applications, Multimedia Development Corporation (ed.) MDEC, Cyberjaya, 1-50.

NEAC, (2010). ‘National Economic Model,’ [Online], [Retrieved August 15, 2010], http://www.neac.gov.my/content/download-option-new-economic-model-malaysia-2010.

Norshuhada, S. & Syamsul, B. Z. (2010). “Mobile Game-Based Learning with Local Content and Appealing Characters,”IJMLO 4(1), 55-82.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Qing, L. Y., (2010). “M’sia’s Rural Areas Lagging with Broadband,” [Online], [Retrieved August 26, 2010],http://www.zdnetasia.com/m-sia-s-rural-areas-lagging-behind-with-broadband-62202341.htm?scid=nl_z_ntnd.

Publisher

Quinn, C. N. (2011). ‘Designing mLearning: Tapping into the Mobile Revolution for Organizational Performance,’ Pfeiffer, San Francisco California USA, 1-223.

Publisher – Google Scholar

SKMM Content Forum, (2004). ‘The Communications and Multimedia Content Forum of Malaysia,” Content Code no 6,SKMM, Cyberjaya Malaysia, [Online], [Retrieved Sept 30, 2010],http://www.skmm.gov.my/link_file/registers/cma/commindcode/pdf/ContentCode.pdf.

Publisher

SKMM Roles, (2010). “Roles and Responsibilities,” SKMM, [Online], [Retrieved Sept 30, 2010],http://www.skmm.gov.my/index.php?c=public&v=art_view&art_id=20.

Publisher

The Star, (2010). ‘Telcos Should Have More Cultural Content: Rais,’ [Online], [Retrieved August 15, 2010],http://thestar.com.my/news/story.asp?file=/2010/1/19/nation/20100119201644&sec=nation.

Publisher

UNESCO, (2001). “Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity,” [Online], [Retrieved August 15, 2010],http://www2.ohchr.org/english/law/pdf/diversity.pdf.

Publisher

UNESCO, (2009). ‘UNESCO World Report: Investing in Cultural Diversity and Intercultural Dialogue,’ UNESCO, Paris, 1-420.