Introduction

There has been a fundamental change in international economy, especially so in the last decade. Emerging and developing countries have significantly increased their weight in global Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and especially in global economic growth; in particular, they have been responsible for most of the growth in the world economy since the 2007-2008 global financial crisis (Sen, 2000; Sachs, 2005 and 2011; Herbst and Mills, 2012; Griffith-Jones, 2014). Indeed, among these emerging economies, few countries have been held in equal measures of consternation and admiration as Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa, known collectively as BRICS. The extent to which they have transformed their economies and extended their tentacles across the world within a relatively short period of time has been subject to intense interest and debates (Alao, 2011; Chidozie, 2014). These discussions are informed by two dominant positions; while some view their rapid economic development as possible templates for other developing countries to attain the economic advancement that has eluded them since independence, others believe that aspects of their policies caution against using the BRICS, or at least some of them as models for developing nations (Alao, 2011:5).

More fundamentally, the BRICS account for 40% of the world’s population and 20% of the world’s GDP (CNN.com, 2014). In addition, the recently concluded plans and the consequent announcement by the BRICS leaders to set up BRICS Development Bank (BDB) which would fund long-term investment in infrastructure and more sustainable development in these countries have heightened the suspicion of the international community and improved the global reputation of these emerging economic giants (CNN.com, 2014; Graffith-Jones, 2014). If these conditions are juxtaposed with the growing discontentment, indeed resentment of the developing economies against the traditional international economic institutions (International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank), especially given the latter’s penchant to undermine the economic institutions of the former through strangulating economic policies, the picture becomes grimmer. It is therefore, not surprising that the G20, at their recent pre-summit briefing, gave the IMF and World Bank an ultimatum which expired 31st July, 2014 to initiate reforms or risk mass repudiation of their policies (CNN.com, 2014).

In view of the above, the growing concern over the placement of Nigeria, arguably one of the four largest economies in Africa, by far the continent’s largest market and the 26th largest economy globally, with an estimated GDP of $509.9 billion, following the recent rebasing of her economy within this emerging developing economic construct, particularly the BRICS becomes pertinent (Onu, 2010; Dallaji, 2012; Stuenkel, 2013; Zabadi and Onuoha, 2012; Niyi-Akinmade, 2014:29). In other words, the increasing debate on the heels of the displacement of South Africa by Nigeria as the largest economy in Africa, following the IMF and World Bank monitored rebasing in June, 2014 makes this study very relevant in contemporary international economic relations (CCR Report, 2012; Fioramonti, 2013). More so, Nigeria’s radical shift in her foreign economic policy since 1999, which has given rise to the increasing penetration of her economy by the BRICS, throws up the complexities in her regional economic relations (Alao, 2011; Esidene et al, 2012).

Furthermore, the discourse on Nigeria’s economic performance over the years has been anchored on the country’s benchmark from independence, in comparison to other regional powers in Asia and Africa (Onimode, 2000). For instance, Herbst and Mills (2012) argued that:

In 1965, Nigeria had a higher per capita GDP than Indonesia: by 1997, just before the financial crash, Indonesia’s per capita GDP had risen to more than three times that of Nigeria. Ghana had a higher GNP per capita in 1957 than South Korea. In 2011, according to the IMF, the average income of South Koreans (US$20 591) was about 16 times that of Ghanaians (US$1 312), the former well above and the latter well below the global average of US$9 218. When Malaysia gained independence in 1957, it had a per capita income less than that of Haiti. But at the end of the 20th century, when Haiti was the poorest country in the Americas (with a per capita income of US$673), Malaysia (US$8 423) had a standard of living higher than that of any major economy in that region, save for the US and Canada. Comparisons between Asia and Africa are stark even in the case of countries with similarities in their economic make-up and political histories, such as Indonesia and Nigeria (Herbst and Mills, 2012:159).

To this end, contemporary scholars of development studies have postulated acronyms such as Mexico, Indonesia, Nigeria and Turkey (MINT); Brazil, South Africa, India and China (BASIC); India, Brazil and South Africa (IBSA); South Africa, Algeria, Nigeria and Egypt (SANE); Mexico, Indonesia, South Korea and Turkey (MIKT); Northern rim countries – Canada, Russia, Scandinavia, and the northern United States (NORCS); Portugal, Italy Greece and Spain (PIGS); and Turkey, India, Mexico, Brazil and Indonesia (TIMBI) as models of regional political-economic integration (O’ Neil, 2001and 2012; Mokoena, 2007; Qi, 2011; Keating, 2012; Stuenkel, 2013). Among these models and constructs, however, BRICS model remains the most workable and globally representative in contemporary regional economic studies, particularly in the context of South-South Cooperation.

In view of this background, the paper is partitioned into four sections, conveniently accommodating some sub-sections. Following this introduction, the second part of the paper probes into the theoretical issues in foreign economic relations with a view to bridging the analytical gaps in literature. The third part of the paper discusses Nigeria’s foreign economic relations with the BRICS economies. The fourth section concludes the paper.

Theoretical Issues in Foreign Economic Relations

Scholars of international relations and particularly development studies have often viewed inter-state relations from the perspective of the North-South divide. The North represents the advanced societies of Western Europe, North America and Japan with intimidating Gross Domestic Products (GDPs) and other economic indices that suggest development; the South, on the other hand, represents the countries of Africa, Asia (with the exception of ‘the newly industrialised countries’ of East Asia) and Latin America, with low GDPs in the global economic mainstream (Therien, 1999; Chidozie, 2014:20).

This latter group of countries have been characterised as ‘underdeveloped’ countries, with ‘backward economies’ and by implication, dependent on the former group of countries. To this effect, this general description accounts for the structuralists’ view of international system, accentuated by ‘centre/periphery’ or ‘metropole/satellite’ description of the world divide between the developed and underdeveloped countries respectively by mainstream scholars who belong to the underdevelopment and dependency school of thought (Gunder, 1967 ; Amin, 1974; Ake, 1981).

To be sure, the North-South cleavage does continue to be an area of reflection in international relations, but for most scholars, however, the parameters of the debate have changed radically. Explanations of this evolution vary enormously. For some, new attitudes have formed, such that ‘the traditional North-South divide is giving way to a more mature partnership’ (Haq, 1995:204). Others maintain that the South – or the Third World – ‘no longer exists as a meaningful single entity’, or that it ‘has ceased to be a political force in world affairs’, judging by significant differences in their levels of development as a ‘result of variations in the gains of globalisation’ (Gilpin, 1987:304).

Others suggest that ‘the North is generating its own internal South’ and that ‘the South has formed a thin layer of society that is fully integrated into the economic North’ (Cox and Sinclair, 1996:531). As demonstrated by these myriads of opinions, the image of a polarisation between a Northern developed hemisphere and a Southern developing hemisphere no longer offers a perfectly clear representation of reality. In short, the understanding of international political economy has been substantially transformed over recent years; and it is precisely the nature of these transformations that is the focus of this study.

Similarly, economic foundation of foreign relations has often been ignored in regional studies, especially as it concerns developing economies in Africa. The reasons for this lacuna in contemporary literature are not far-fetched. The dominance of power politics theories has relegated economic factors to a peripheral status and a discussion of economic foreign policy raises several theoretical problems, since conventional foreign policy literature does not bequeath a theoretical paradigm that is able to synthesize politics and economics, domestic and foreign policy and the idea of an economic foreign policy orientation to contemporary scholars (Olusanya, 1988; Bangura, 1989; Olukoshi, 1991; Amale, 2002). Indeed, Kunle Amuwo’s argument seems apt as he posited that:

The naivety of African states- and perhaps also the opportunism of their bankrupt ruling class- is the tendency to extricate the economy from the political (Amuwo, 1991:85)

Attempts made to fill these theoretical gaps in literature have led scholars to re-visit the two broad competing models of theoretical understanding that seek to explain international economic relations within the context of development. Thus, theorists vary in their approaches to the factors that contributed to the development of underdevelopment of the Third World countries in relation to developed countries. While the bourgeois scholars argued that the underdevelopment and dependency situation of the Third World was due to the internal contradictions of this group of countries arising from bad leadership, mismanagement of national resources and elevation of personal aggrandisement and primordial interests over and above national interest, the neo-Marxian scholars, on the other hand, submitted and insisted that, what propelled the development of the developed countries also facilitated, in the same measure, the underdevelopment of the underdeveloped countries. These, according to the latter group, are colonialism, slave trade and unequal exchange (Rosenstein, 1943; Prebisch, 1950; Baran, 1957; Hirschman, 1958; Rostow, 1960; Amin, 1974; Rodney, 1974; Aluko and Arowolo, 2010).

Specifically, the thrust of modernisation theories of development is that underdevelopment is an original state with the concomitant characteristics of backwardness or traditionalism, and that abandoning these characteristics and embracing those of the developed countries constitutes the route to economic development and cultural change (Martinussen, 1999). On the other hand, underdevelopment and dependency theories contend that, underdevelopment, far from being an original or natural condition of the poor societies, is a condition imposed by the international expansion of capitalism and its inalienable partner, imperialism (Offiong, 1981; Landes, 2000). That is to say, African, indeed, Third World underdevelopment is the result of economic imperialism and the consequent dependency.

Nigeria and the BRICS Economies

An attempt is made in the following section to delineate the dynamics of Nigeria’s foreign economic relations with the BRICS countries.

Nigeria and Brazil

Nigeria and Brazil signed a bilateral agreement in September 2005 which was targeted at cementing their economic and cultural ties. The agreement focused on four major areas of trade and investment, technical co-operation, cultural revival and regular political consultations. Since then, the value of bilateral trade has reached over $2 billion and the joint co-operation profile has covered virtually every facet of human activity (Alao, 2011:19). To be sure, between 2003 and 2005, Nigeria’s merchandise exports to Brazil increased from nearly $1.5 billion to $5 billion, climaxing at $8.2 billion in 2008, thus, placing Nigeria as the fifth-highest exporter of goods to Brazil, after the US, Germany, Argentina and China and making Brazil currently the second largest importer of Nigerian products worldwide (Alao, 2011:9).

The bulk of Nigeria’s trade with Brazil is in oil and gas; and Nigeria is Brazil’s largest source of petroleum. However, in recent times the two countries have identified other areas of mutually beneficial trade and co-operation. According to the report released by the African Development Bank Group (ADBG, 2011), Nigeria and Brazil have perceived the need to collaborate in the area of drugs and narcotics control; and most importantly, bio-fossils and its use of ethanol as an alternative to fuel (where Brazil has assumed a global leadership) as issues of potential interest between the two countries. To this end, Brazil announced the plan to build a ‘Biofuel Town’ in Nigeria in 2007 and proposed initial project of US$100 million for the production of Ethanol from sugar cane and palm oil (ADBG, 2011:5).

Furthermore, Nigeria and Brazil signed a joint agreement on energy co-operation in August 2009, following which an Energy Commission was established between the two countries. Consequently, Brazil expressed interest in completing the development of the Zungeru Hydropower Plant and financing the Mambilla Hydropower Project under a partnership that would allow the country to help develop Nigeria’s power industry. In return for Brazil’s participation in two hydropower projects, Nigeria will grant the former access to its oil and gas industry (Alao, 2011:20).

However, the most recent effort between Nigeria and Brazil to foster co-operation in trade and investment was the establishment of a Bi-National Commission, which was set up in 2012, under the auspices of the Nigerian-Brazilian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (NBCCI). In this regard, the Chamber has provided the vehicle for forging bilateral ties between both countries by successfully organising two Brazilian Official Trade Missions to Nigeria in 2013, and a reciprocal Trade Mission to Brazil in the same year. These Trade Missions covered various areas of business endeavours, including Agricultural and Agro-Allied, Technology, Infrastructure, Power, Mining, Oil and Gas, Construction, Commerce, Aviation, Finance/Banking, Women Empowerment, Culture and Tourism (NBCCI Report, 2012).

Nigeria and Russia

Russo-Nigerian relations have progressed considerably since the latter’s independence culminating in the signing of series of Memorandum of Understanding (MOUs) in 2008. The first of these agreements was to regulate the peaceful use of nuclear energy, while the second envisaged the participation of Gazprom, the Russian-based energy corporation, in the exploration and development of oil wells and gas reserves in Nigeria. Specifically, Russia’s economic interest in Nigeria is in the areas of infrastructure development, the ferrous and nonferrous metals industry, electric power generation, including nuclear energy, and the extraction of hydrocarbon and other raw minerals. For its part, Nigeria is interested in the electricity sector (Alao, 2011:15).

In recent time however, Nigeria and Russia have started exploring discussions on space technology, nuclear energy and partnership in other technical fields. The countries have signed a nuclear agreement between the Nigerian Nuclear Regulatory Authority and the Russian State Atomic Corporation to explore and develop gas and hydrocarbon-related projects in Nigeria. In 2010 trade, between the two countries reached $300 million, having recorded a balance of trade to the tune of $1.5 billion mark in 2009; thus Nigeria became Russia’s second-largest trading partner in sub-Saharan Africa after South Africa (Anofi, 2010; Alao, 2011:15).

Nigeria and India

Nigeria and India signed strategic partnership deal called the Abuja Declaration, comprising four agreements: two MOUs on promoting interaction between foreign office backed institutes; one MOU on defence co-operation; and a protocol for foreign office consultations. Prior to this time, Nigeria and India had lacked institutional framework to back investments and commerce, thus, it was agreed that these pacts would set the stage for a more intensive relationship between the two countries. Thus, the areas covered by the Abuja Declaration were keys to promoting trade, investment and cultural exchange programme between both countries (Alao, 2011:18).

Ugo (2010) argued that the understanding of Nigeria-India relations would be better situated within the context of the dominant competition between India and China, two leading countries in the BRICS bloc. According to her, India, like China, is positioning itself to becoming an economic power in the next decade. She asserted that India is the largest democracy in the world, with an estimated 1.2 billion population, behind China’s 1.4 billion; world leader in innovation of ultra inexpensive cars produces the lowest cost car in the world – the “Nano” car from Tata Motors and pulling her weight also in supplying global human resources, as well as in computer software business. She submitted that, India is currently the 12th largest economy in the world based on World Bank rating and also ranked the 45th in the internationally respected Legatum Prosperity Index, 2009.

With these economic credentials, Nigeria cannot ignore her relations with India in the 21st century international economic relations. According to Alao (2011), Nigeria’s contemporary relations with India are in the areas of trade and commerce, even though their relations cut across a broad spectrum. He argued that trade between the two countries by 2010 was approximately $10.7 billion, of which $8.7 billion was to Nigeria’s advantage. He stressed that, by this figure, Nigeria is currently believed to be India’s largest trading partner in Africa. He concluded that the key areas identified include oil and gas (Oil and Natural Gas Corporation Videsh Limited), medical and pharmaceutics, banking (involvement with the IBTC), telecommunication (Bharti Airtel invested $600 million to take over Zain in 2010), retail, movies and entertainment, and vehicle importation (DANA and Stallion Groups) (Alao, 2011:18).

Nigeria and China

Given the dynamic nature of China’s growing engagement with Africa, as well as the ad hoc and limited engagement that preceded it, an examination of Nigeria-China relations is mostly grounded in an assessment of how the rising interest of China in Africa significantly affects Sino-Nigeria relations. In other words, an appraisal of Nigeria-China relations must necessarily be seen in the light of the dynamics of China’s renewed engagement with Africa, especially since the end of the Cold War in 1989 (Srinivasan, 2008:334; Alli, 2010:105; Ariyo, 2010:134; Oche, 2010:139). In view of the controversy that has bedevilled the relations between Nigeria and China, attempt has been made in scholarly circles to describe the nature of their engagement as “that of a giant to a bigger giant” (Owoeye and Kawonishe, 2007:534) and “a friendship between most unequal equals” (Bukarambe, 2005:249).

Indeed, nowhere is this lopsided relationship more pronounced than in the area of economic transactions – a prevailing feature of the international economic diplomacy of the 21st century. According to Bukarambe (2005), the economic points of contact between Nigeria and China are so diverse to the extent that the latter’s advantages are very manifest and the former has no reciprocity. He argued that, in view of the first bilateral trade agreement signed between the two countries on November 3, 1972, (other agreements have long been added to this), Chinese companies have been involved in projects covering roads and bridges, ports, oil fields, bore holes, agriculture, and power distribution/supply. He stressed that China acknowledges that up to 90 Chinese companies are involved in Nigeria in various sectors covering trade, investments and construction (Bukarambe, 2005:252).

Bukarambe (2005) further cited Chinese Haier Company which is involved with PZ in the production of air-conditioners, electronics and refrigerators; China National Petroleum Company (CNPC) and the China National Petroleum and Chemicals Corporation (CNPCC), which are engaged in construction in association with Shell Petroleum (the largest foreign Oil Company in Nigeria) and development of marginal fields respectively, as veritable examples of Chinese trade interests in Nigeria. He submitted that, in all, Chinese construction companies got contracts worth up to $200 million in 2000 (Bukarambe, 2005). These extensive trade relations warranted that, by 2009, Nigeria was among the leading two-way trade partners of China in Africa, alongside countries such as Angola, South Africa and Sudan; and the second-highest African importer from China, after South Africa (Alao, 2011:16).

In the same vein, Owoeye and Kawonishe (2007), argued that one major problem in the relationship between Nigeria and China is the permanent trade deficit. According to them, since the formalisation of relations in 1971, the balance of trade has always been in favour of China. They stressed that, although trade between both states reached $1.86 billion in 2003 representing a 59% growth and further grew by 17.6% to $609 million with Nigeria’s export to China registering a growth of 330%, during the first four months of 2004; and in April 2011, trade between the two countries had reached a new height of $ 7.76 billion, thus making Nigeria the fourth-largest trading partner and the second-largest export market of China in Africa, Nigeria still recorded a balance of trade deficit. They attributed this trade imbalance to the nature of Chinese export and import to Nigeria, showing that China exported manufactured and industrial items to Nigeria and imported unprocessed agricultural and mineral items from it. They concluded that, China has set up more than thirty solely funded companies and joint ventures in Nigeria, confirming that the former has a net industrial and developmental advantage over Nigeria (Owoeye and Kawonishe, 2007:544).

By way of comparative advantage, Aja (2012) posits that, Nigeria is still a struggling economy while China is both the fastest growing and second largest economy in the world. According to him, the present locale of China in the world economic system cannot be ignored by a struggling economy like Nigeria, and logically too, in a fast changing world system, China cannot ignore Nigeria in both economic and overall strategic considerations in Africa. He stressed that Nigeria remains a potential market in the world at any time, and strategically, China needs Nigeria to consolidate its new-found relations in Africa. He however, regrets that Nigeria’s new relationship with China will be conditioned by the structural economic dependency factor against Nigeria, concluding that while China’s economy is heavily diversified with the capacity building to export varieties of produce, Nigeria is still over-dependent on oil as the commanding height of its economy (Aja, 2012).

Incidentally, Alao (2011) argued that although China has a range of interests in Nigeria, its main trade interest is oil. According to him, several oil deals have been signed over the last few years, the most significant being the agreement that involved China investing $4 billion in Nigeria’s infrastructure in return for the first refusal rights on four oil blocks in 2008. He stressed that at the centre of most of Nigeria’s economic diplomacy towards China is the principle of ‘exchanging oil for development’, citing a number of rail construction contracts signed in April 2011 between the Nigerian Government and a Chinese company named China Gezhouba Group Corporation, such as the three Eastern rail lines (463 kilometre from Port Harcourt to Makurdi; the 1, 016 kilometre line from Makurdi to Kuru, with the inclusion of the spur lines to Jos and Kafanchan; and the 640 kilometre line from Kuru to Makurdi) as a validation of such diplomatic engagement. He concluded that, this oil for development deal inevitably put China on a collision course with Nigerian militants fighting the Nigerian state over the management of oil in the country’s Niger Delta, a course that manifested in hostage taking of the Chinese oil workers and the consequent payment of ransoms to free the workers (Alao, 2011).

Salter (2009), on the other hand, however, contended that the ‘oil for infrastructure’ model adopted by former President Obasanjo in his dealings with China is dead. According to him, the model has been replaced by one in which Chinese energy companies gain access to the country’s oil resources by buying stakes in established companies. He argued that the termination of the ‘oil for infrastructure’ approach by the current Nigerian government demonstrates an incompatibility between this model and the Nigerian electoral cycle, which is designed to alternate rule by rotating power among different personalities with varying ideologies. He nonetheless anticipated that Chinese multinational companies that would have benefited from these infrastructure projects would continue to grow their Nigerian market share due to their competitive advantages in price, risk appetite and access to credit. He concluded that the Nigerian government would derive more benefit from its relations with China first by improving its negotiation capacity and, secondly, through a re-evaluation of its negotiation positions, drawing on the experience of China in its dealings with the West, particularly concerning technology transfer and concessional credit (Salter, 2009).

Nigeria and South Africa

In the received literature on African politics, scholars have expressed concern on the nature of the relationship between Nigeria and South Africa and the exact roles they are expected to play in the continent’s development. Even though, scholars are already contesting the hegemonic status of Nigeria and South Africa in Africa, others have reached a consensus on the historical roles these countries have been playing in the continent (Gwendolyn and Lyman, 2001; Adebajo and Landsberg, 2003; Alden and Soko, 2005; Adebajo, 2007; Landsberg, 2008; Mikell, 2008; Chidozie, 2012; Dallaji, 2012; Zabadi and Onuoha, 2012).

In comparative terms, Nigeria and South Africa remain Africa’s regional economic and military powerhouses. Together, they account for 55% of the total Gross National Product (GNP) of the African continent and represent 25% of the population of the continent. As centres of political, economic, military and diplomatic gravity in West and Southern Africa, Nigeria and South Africa +respectively have risen to and fulfilled the popular expectation that both of them, working together and sharing broadly the same goals for Africa, are capable of positively influencing developments in Africa in the image of their political preferences (Akindele, 2007:317; Dallaji, 2012:267).

On the economic sphere, the difference between the two countries is also clear. Following a recent re-basing exercise of Nigeria’s GDP conducted by a team of local and international experts, including officials of International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank and the African Development Bank (ADB) which took care of some sectors of her economy that have taken dominance since 1990, such as telecommunications, information technology, music, online sales, airlines, and Nollywood film production, the country’s GDP rating was dramatically altered. Consequently Nigeria’s GDP is at $509.9 billion above that of South Africa (Niyi-Akinmade, 2014:30). Similarly, over the next four decades, for instance, Nigeria’s economy is expected to grow at between 5% and 7%, which is almost twice that of South Africa with a projected real GDP growth rate of 3.5% (Onu, 2010; Centre for Conflict Resolution, CCR, 2012:3).

Thus, Nigeria-South Africa bilateral relations is shaped by the fact that South Africa is the continent’s strongest and most versatile economy, while Nigeria is Africa’s largest consumer market (Adebajo and Landsberg, 2003; Agbu, 2010; Zabadi and Onuoha, 2012). We therefore note that, while South Africa has advantage over Nigeria in areas of technology and infrastructure, Nigeria has the advantages of large market potentials for investment and large pool of human resource. Furthermore, Nigeria’s trade link to South Africa is through one commodity (oil), while South Africa’s trade is diverse and includes a range of products that Nigeria’s massive consumer market clearly wants. Indeed, by June 2002, Nigeria had become South Africa’s largest trading partner in Africa behind Zimbabwe, Mozambique, and Zambia. In West Africa, Nigeria is already South Africa’s largest trading partner, with bilateral trade increasing from $100 million in 1999 to reach $5 billion in 2012 (Zabadi and Onuoha, 2012:397).

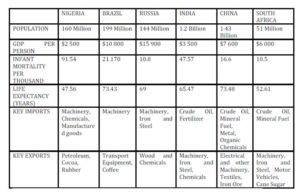

Table 1: Overview of Nigeria and the BRICS

Sources: Alao, A (2011) Nigeria and the BRICs: Diplomatic, Trade, Cultural and Military Relations. South Africa: SAIIA, Occasional Paper No. 101; Chidozie, F.C (2014) Dependency or Cooperation?: Nigeria-South Africa Relations (1960-2007). Unpublished PhD Thesis, Covenant University, Ota: Nigeria; World Bank (Stuenkel, 2013:312)

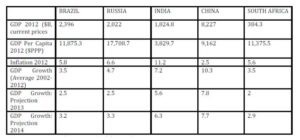

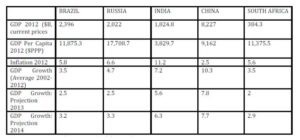

In view of the comparative nature of the work, Table 2 below presents key economic indicators of the BRICS economies to further demonstrate the high rate of their economic growth. More so, current projections by major international economic institutions like the IMF and the World Bank validate the under-listed economic indices, despite contrary speculations and caution on the part of some.

Table 2: Key Economic Indicators of the BRICS

Source: International Monetary Fund (2013:1)

Conclusion and Recommendations

This paper has attempted to situate Nigeria in the current regional politico-economic construct, BRICS. It argued that the BRICS has remained the most viable and globally representative model for driving development among emerging economies. This has become more relevant in view of the fact that the current economic crises in Europe have defied every foreseeable solution, even by the IMF and the World Bank. Indeed, previously strong economic giants like Britain, Germany, Italy, Belgium, Greece and the United States have become sources of concern to many international observers. The recent collapse of the French government and its subsequent replacement with a new administration, the latest in the series of economic risk that Europe has become, makes the situation bleaker. In view of this, the study makes a very strong case for South-South political-economic cooperation as the only sustainable catalyst for global dominance.

References

1. African Development Bank (ADB) Report (2011). “Brazil’s Economic Engagement with Africa”. Volume 2, Issue 5, May

2. Adebajo, A (2007) “South Africa and Nigeria in Africa: An Axis of Virtue?, in Adebayo Adedeji and Chris Landsberg (eds.), South Africa in Africa: The Post-Apartheid Era, Cape Town: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press

3. Adebajo, A and Landsberg, C (2003) “South Africa and Nigeria as Regional Hegemons”, in Mwesiga Baregu and Christopher Landsberg (eds.), From Cape to Congo: Southern Africa’s Evolving Security Challenges, London: Lynne Rienner Publishers, pp. 171-203

Publisher – Googlescholar

4. Agbu, O. (2010), ‘’Nigeria and South Africa: The Future of a Strategic Partnership’’, in Osita C. Eze (ed.), Beyond 50 Years of Nigeria’s Foreign Policy: Issues, Challenges and Prospects, Lagos: NIIA Publications.

Publisher – Googlescholar

5. Aja, A.A. (2012) “Nigeria-China Relations: Dynamics, Challenges and Strategic Options”, in Thomas A. Imobighe and Warisu O. Alli (eds.) Perspectives on Nigeria’s National Politics and External Relations: Essays in Honour of Professor A. Bolaji Akinyemi, Ibadan: University Press PLC, pp. 347-366

6. Ake, C., (1981) A Political Economy of Africa, Longman Group Limited, England

7. Akindele, R.A., (2007) ‘’Nigeria’s National Interests And Her Diplomatic Relations With South Africa’’, in B. A. Akinterinwa (ed.), Nigeria’s National Interests in a Globalising World: Further Reflections on Constructive and Beneficial Concentricism, Vol. 111, Ibadan: Bolytag International Publishers

8. Alao, A (2011) “Nigeria and the BRICs: Diplomatic, Trade, Cultural and Military Relations”, South African Foreign Policy and African Drivers Programme: SAIIA: Occasional Paper, No.101

9. Alao, A (2011) “Nigeria and the Global Powers: Continuity and Change in Policy and Perceptions”, South African Foreign Policy and African Drivers Programme, SAIIA Occasional Paper Series No 96,

10. Alden, C and Soko, M (2005) “South Africa’s Economic Relations with Africa: Hegemony and its Discontents”, Journal of Modern African Studies, Vol. 43, No. 3, pp. 367-392

Publisher – Googlescholar

11. Alli, W.O. (2010) “China-African Relations and the Increasing Competition for Access to Africa’s Natural Resources”, Lagos: Nigerian Institute of International Affairs, pp. 105-121

12. Aluko, F. and Arowolo, D. (2010) “Foreign Aid, the Third World’s Debt Crisis and the Implication for Economic Development: The Nigerian Experience”. African Journal of Political Science and International Relations, Vol. 4(4), pp. 120-127

Googlescholar

13. Amale, S.A., (2002), “The Constraints of Nigeria’s Economic Diplomacy”, in Ogwu U. Joy and Olukoshi O. Adebayo (eds.), The Economic Diplomacy of the Nigerian State, Lagos: Nigerian Institute of International Affairs, pp. 134

14. Amin, S., (1974), Accumulation on a World Scale, New York, Monthly Review Press (1970)

Googlescholar

15. Amuwo, K. (1991) “The Relevance and Irrelevance of Nigeria’s Economic Diplomacy” in U. Joy Ogwu & Adebayo Olukoshi (eds.), Economic Diplomacy in the Contemporary World and the Nigerian Experience. Nigerian Journal of International Studies, Vol. 15 No 1 and 2 pp. 79-92

16. Anofi, D (2010) “Nigeria, Russia Trade Volume Hits $1.5b Mark”, The Nation, Lagos, 14 January

17. Ariyo, A.C. (2010) “The New Scramble for Africa: Africa-China Engagement”, Lagos: Nigerian Institute of International Affairs, pp. 123-137

18. Bangura, Y., (1989), “The Recession and Nigeria’s Foreign Policy”, Lagos, Nigerian Journal of International Affairs, Volume 15, Number 1, p. 131

19. Baran, P., (1957), The Political Economy of Growth, New York, Monthly Review Press.

20. Bukarambe, B. (2005) “Nigeria-China Relations: The Unacknowledged Sino-Dynamics”, in U, Joy Ogwu (ed.) New Horizons for Nigeria in World Affairs, Lagos: Nigerian Institute of International Affairs, pp. 231-258

21. CCR (2012) “The Eagle and the Springbok: Strengthening the Nigeria/South Africa Relationship”, Policy Advisory Group Seminar Report: The Moorhouse, Lagos, Nigeria, 9-10 June

22. Chidozie, F. C., (2012) “Economic Globalization in the 21st Century and Nigeria-South Africa Relations: Prospects and Challenges, African Journal of Humanities and Globalization, Vol.2 No 1, pp.31-54

23. Chidozie, F.C., (2014) “Dependency or Cooperation? Nigeria-South Africa Relations (1960-2007). Unpublished PhD Thesis. Ota: Covenant University

Googlescholar

24. Cox, R. W and Sinclair, T.J (1996) Approaches to World Order, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

25. Dallaji, I.A. (2012) “Nigeria-South Africa Relations: Partnership, Reversed Patronage or Economic Imperialism”, in Bola A. Akinterinwa (ed.) Nigeria and the World: A Bolaji Akinyemi Revisited, Lagos: NIIA, pp. 265-283

26. Esidene, E.C, and Yatu, L.N. (2012) “Historical Context of the Incorporation of Africa in International Politics”. African Journal of Social Sciences, Vol. 2 Number 3 pp. 27-42

27. Fioramonti, L (2013) “Nigeria VS South Africa in Flawed GDP Battle”, Mail & Guardian Business, June 28 to July 4

28. Gilpin, R (1987) The Political Economy of International Relations, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press

Googlescholar

29. Griffiths-Jones, S (2014) “A BRICS Development Bank: A Dream Coming True?” Discussions Papers on United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, No. 215, March, 2014

Googlescholar

30. Gunder, F.A., (1967), Capitalism and Underdevelopment in Latin America: Historical Studies of Chile and Brazil, New York, Monthly Review Press.

31.Gwendolyn, G. and Princeton N. L., (2001), “Critical US Bilateral Relations in Africa: Nigeria and South Africa” (Washington, DC: Centre for Strategic and International Studies)

32. Haq, U.M (1995) Reflections on Human Development, New York: Oxford University Press

33. Herbst, J and Mills, G (2012) Africa’s Third Liberation: The New Search for Prosperity and Jobs. Johannesburg: South Africa, Penguin Books

34. Hirschman, A. O., (1958), The Strategy of Economic Development, New Haven, CT, Yale University Press

Googlescholar

35. Keating, J.E. (2012) “More than BRICS in the Wall: What do all those Acronyms Stand For?”. Democracy Lab Magazine, March/April

36. Qi X (2011) “The Rise of BASIC in UN Climate Change Negotiations”. South African Journal of International Affairs 18(3):295-318.

Publisher – Googlescholar

37. Landes, D. (2000) “Culture Makes Almost All the Difference” in Lawrence E. Harrison and Samuel P. Huntington (eds.) Culture Matters: How Values Shape Human Progress, New York: Basic Books, pp. 2-13

38. Landsberg, C (2008) “An African Concert of Powers?: Nigeria and South Africa’s Construction of the AU and NEPAD”, in Adekeye Adebajo & Abdul Raufu Mustapha (eds.), Gulliver’s Troubles: Nigeria’s Foreign Policy after the Cold War, South Africa: University of KwaZulu Natal Press, pp. 203-219

39. Martinussen, J. (1999), Society, State and Market: A Guide to Competing Theories of Development, Zed Books Ltd, New York.

40.Mikell, G. (2008) “Players, Policies and Prospects: Nigeria-US Relations”, Adekeye Adebajo & Abdul Raufu Mustapha (eds.), Gulliver’s Troubles: Nigeria’s Foreign Policy after the Cold War, South Africa: University of KwaZulu Natal Press, pp. 281-313

41. Mokoena R. (2007) “South-South Cooperation: The case for IBSA. South African Journal of International Affairs 14(2):125-145.

42. NBCCI (2012) Report: http://nigeriabrazilchamber.org/index.php?option=com

43. Niyi-Akinmade, T. (2014) “What Manner of Growth? A Rebased Gross Domestic Product, GDP, by Nigeria Provokes Skepticism Among the Citizens”. Newswatch Magazine May:29

44. Oche, O. (2010) “Nigeria-China Relations: Sources and Patterns of External Interests”, Lagos: Nigerian Institute of International Affairs, pp. 139-159

45. Offiong, D. A., (1981), Imperialism and Dependency, (Enugu: Fourth Dimension Publishers).

46. Olukoshi, A., (1991), Crisis and Adjustment in the Nigerian Economy, Lagos, JAD Publishers Ltd, p. 162

47. Olusanya, G., (1988), Forward to Richard Akindele and Bassey Ateh (eds): Nigeria’s Economic Relations with the Major Developed Market-Economy Countries, 1960-1985, Lagos: Nigerian Institute of International Affairs, p. Ix

48. O’Neil, J. (2001) “The World Needs Better Economic BRICs”. Global Economic Paper Series, Goldman Sachs

49. O’Neil, J. (2012) ““Leading a continent to a place in Brics and beyond.” Times Live, April 1. http://www.timeslive.co.za/local/2012/04/ 01/leading-a-continent-to-a-place-in-brics-and beyond.

50. Onimode B., (2000) Africa in the World of the 21st Century, Ibadan: Ibadan University Press

51. Onu, E (2010) “Nigeria to Emerge Africa’s Biggest Economy”, published in Thisday Newspapers, June 9, 2010

52. Owoeye, J. and Kawonishe, D. (2007) “Nigeria’s Relations with China and Japan: The Dynamics of Rapprochement”, in B. A. Akinterinwa (ed.), Nigeria’s National Interests in a Globalising World: Further Reflections on Constructive and Beneficial Concentricism, Vol. 111, Ibadan: Bolytag International Publishers, pp. 521-569

53. Prebisch, R. (1950) The Economic Development of Latin America and its Principal Problems, New York: United Nations.

54. Rodney, W. (1972) How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, Lagos: Panaf Publishing

Googlescholar

55. Rosenstein, R.P. (1943) “Problems of Industrialization of Eastern and South-Eastern Europe”. Economic Journal, June-Sept. In: Meier

Googlescholar

56. Rostow, W. W., 1960, The Stages of Growth, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

57. Sachs, J (2005) The End of Poverty: How We Can Make It Happen In Our Lifetime. London: England, Penguin Books

Googlescholar

58. Sachs, J (2011) The Price of Civilization: Economics and Ethics after the Fall. London: The Bodley Head

Googlescholar

59. Salter, G.M. (2009) “Elephants, Ants and Superpowers: Nigeria’s Relations with China”, South African Institute of International Affairs (China in Africa Project) Occasional Paper No. 42, pp. 1-32

60. Sen, A. (2000) Development as Freedom. New York: Alfred A. Knopf

61. Srinivasan, S. (2008) “A Rising Great Power Embraces Africa: Nigeria-China Relations”, Adekeye Adebajo & Abdul Raufu Mustapha (eds.), Gulliver’s Troubles: Nigeria’s Foreign Policy after the Cold War, South Africa: University of KwaZulu Natal Press, pp. 334-366

62. Stuenkel, O. (2013) “South Africa’s BRICS Membership: A Win-Win Situation? African Journal of Political Science and International Relations, Vol. 7(7) pp. 310-319

Publisher – Googlescholar

63. Therein, J.P (1999) “Beyond the North-South Divide: The Two Tales of World Poverty”, Third World Quarterly, Vol. 20, No.4, pp. 723-742

Publisher – Googlescholar

64. Ugo, N. (2010) “Nigeria: Possible Lessons from the ASEAN Development Model”, in Osita C. Eze (ed.), Beyond 50 Years of Nigeria’s Foreign Policy: Issues, Challenges and Prospects, Lagos: NIIA, pp. 457-487www.cnn.com

65. Zabadi, I.S and Onuoha, F.C (2012) “Nigeria and South Africa: Competition or Cooperation”, in Thomas A. Imobighe and Warisu O. Alli (eds.) Perspectives on Nigeria’s National Politics and External Relations: Essays in Honour of Professor A. Bolaji Akinyemi, Ibadan: University Press PLC, pp. 384-408