Introduction

According to a new World Bank Report[i], Asia Pacific region is faster in aging than the other parts of the world and this could lead to a decline in the size of workforce in the nation and increase in spending on pensions and health care in coming decades. The older population grows by 22 percent in every five years in East Asia and Malaysia is one of the countries.[ii] The higher the older population is in a country, the higher in demand of public spending. Though it is normal for rich countries to spend more on public services, the number of older people Malaysia will have in the next five to ten years is alarming and there is an urgent need for the country to review the efficiency of existing social safety nets for older people

[i] World Bank, 2016, Live Long and Prosper: Aging in East Asia and Pacific, Washington, DC: World Bank, pg. 23.

[ii] Hotez, P.J., 2016. The South China Sea and Its Neglected Tropical Diseases. PLOS Negl Trop Dis, 10(3), p.e0004395.

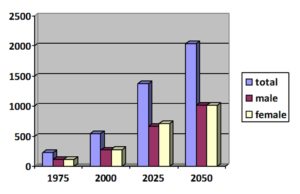

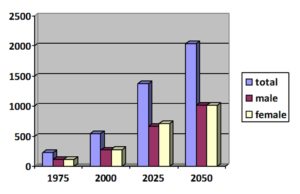

Malaysia Population (1975- 2050) Age 60 and Above In Percentage

Source: World Population Aging, Population Division, DESA, United Nations

Based on the above diagram, it can be seen that older population has been increased over the years in Malaysia. In fact, it has been a trend in Asia Pacific Region. Malaysia is expected to be having 14% of ageing population by the year 2020. The highest number of older population in Asia is in Japan and thus social safety net for older people in Japan will be examined in order to suggest the best practice to be introduced in Malaysia. Interviews have been conducted in selected places and research found that most of the older people in Malaysia are left in rural areas as their children have moved to urban areas in search of better paid jobs. As a result, older parents have to depend on themselves instead of their family. Though it is expected that the state will play a better role in supporting older people, how the state meets that expectation is a key social and political challenge in the coming year. Hence it is best for older people to have their own social safety net without depending much on their children and the Government.

Social Security for Older People in Malaysia

Social Security System is a system which protects and supports people by providing necessary assistance during the time of poverty, unemployment, illness, injury, aging and etc. There are many social security schemes in Malaysia providing the foundation for universal social protection comprising of different social protections. Public pension system is provided for civil servants and Employee Provident Fund (EPF) is provided for those in private sector. In fact, Malaysia Government gives RM300 per month as financial assistance to those who are above 60 years old and do not have family and fixed income.[i] However, these measures are not sufficient to shield the rapid growth of older persons in the country.

Nearly half of the government’s spending has been towards the welfare of elderly people and thus the increase in number of elderly people in the country indeed poses challenges to the government in spending public finances. It is vital that every citizen in their old age has access to healthcare, and should not pressure on the public health system of the government. Hence it is important that those who can afford should rely on private health insurance in order for the government to be able to provide quality assistance to those who cannot afford it.

There are a number of social security schemes and institutions in Malaysia but not all have the ability to address the long term financial commitments and provide security during the old age. Among them, the Employees’ Provident Fund (EPF) which was formed under Employees Provident Fund Act 1991 is a compulsory savings scheme for those who are in Private Sector and one of the main objectives to provide retirement benefits for its members. It acts as retirement savings for all those who are in private sector and manages the fund which is based on the income of individual savings and contributed both by employers and employees. In addition to this, EPF also ensures that the fund is growing over the years. The fund has three accounts, namely, Account I, Account II and Account II. Savings from all these accounts can be fully withdrawn when a member is deceased, incapacitated or leaves for permanent residency outside the country. Funds in Account I which constitute 60% of monthly contribution are meant to be used after the retirement period and members are not allowed to withdraw until the age of 55 years old. Members are also allowed to invest a portion of their savings from Account I in funds approved by the Ministry of Finance.

For those who are in Public Sector i.e. Government’s servants have different type of scheme known as old age pension scheme under the Government Pension Ordinance 1951. This is a non-contributory scheme applicable to the employees of the government, semi-government agencies, local authorities and statutory bodies. It provides security for the retirement age. Civil servants are also entitled to receive the payment of gratuity based on the year of service. In some agencies, they are also eligible to receive certain payment known as a ‘golden hand shake’. Hence, a considerable amount of savings is available for civil servants in addition to pensions. There is also another old age benefit scheme under the Armed Forces Fund Act 1973 but it is only for military personnel. The government has also introduced several schemes for those who are self-employed in order to assist the hard-core poor to venture into income generating activities through micro-credit facilities.

Currently this is the only social safety net available to give coverage for the old age. Recently EPF introduced a new type of saving called PRS (Private Retirement Schemes). However, contribution for this fund is on a voluntary basis for those aged 18 and above and it is managed by private intermediaries approved by the Securities Commission of Malaysia. Since it is on a voluntary basis, not everyone has contributed to this scheme.

Since the time of establishment of EPF on the 1st of October 1951, full withdrawal age is maintained at the age of 55 whereas the life expectancy of Malaysians has increased to age 75. This means that the amount of EPF savings is not sufficient and does not last for these 20 years of old age.

Measures taken by Malaysian Government

EPF scheme does not cover those self-employed, house-wives and those without a fixed income. This category of people does not have a formal social safety net since they are neither covered by EPF nor by the Pension Scheme for Public Sector Employees. The government has introduced 1 Malaysia Retirement Savings Scheme (SP1M) for this category of people in order to get protection during their old age. This Scheme is designed to encourage this category of people to contribute voluntarily based on their affordability for their old age. The contribution can be as little as RM50 with a maximum amount of RM60,000 a year. Members of this scheme are entitled to receive annual dividend that is subject to a minimum dividend rate of 2.5% and eligible to receive Death Benefit (RM2,500) and an Incapacitation Benefit (RM5,000), subject to terms and conditions. To encourage saving, the government gives tax exemption up to RM6,000 per year (with life insurance) and contributes 10% per year subject to a maximum amount of RM120 per year. However, this contribution from the government is only for the period of four (4) years beginning from 2014-2017 and limited to members below age 55.

In addition to this, the government has extended the minimum retirement age to 60 years old beginning from January 2013.

Social Security Net for Older People in Japan

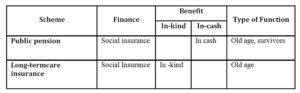

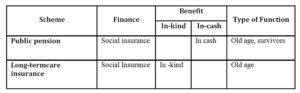

The population in Japan has declined in recent years and the proportion of elder people has reached the highest level in the world as the life expectancy is high. Hence, social security plays a vital role in maintaining older people in the society. There are different types of social security system in Japan; pensions, health and long-term care insurance, public assistance, family policy, policy for people with disabilities and etc. and most of them adopt the social insurance system. The table below explains the social security for old age:

Table 1[ii]

[i] Department of Social Welfare documents, Malaysia (2015)

[ii] Social Security in Japan (2014) by National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, Japan.

The main characteristic of Japan’s Social Security is that it is compulsory for all citizens to register in the public pension and health insurance programmes. Those above the age of 40 years old have to be covered by the long-term care insurance, and other employment related insurances; employment insurance and work-related accident insurance. These social insurances are to be borne by social insurance premiums and supplemented by the tax revenue in the forms of subsidy. The premium is paid by the insured based on their income. The rest of the schemes are financed from the public fund (Tax).

Public Pension consists of public and private pension schemes based on whether governmental or non-governmental servants. Pension system for those who are in private sectors has three tires; Basic Pension, Employees’ Pension Insurance and Optional Scheme.

The first tier, Basic Pension is universal since it covers all residents 20 years old and above. It is mandatory and provides a basic income guarantee for old age. The Basic Pension for those who are self-employed, farmers and unemployed is called the National Pension and operated by the government. The Premium for National Pension is paid by the insured only and is a flat rate for all. All of administrative costs and 50% of benefits are subsidised by the government.

The second tier, Employees’ Pension Insurance is mandatory to all corporations over a certain size and the premium is shared by employers and employees. This is something akin to Employees Provident Fund in Malaysia. This covers most employees and the premium is shared by employers and employees based on the income. Both Basic Pension and Employees’ Pension Insurance are operated by the government.

The third tier, Optional Scheme, is operated either by private corporations (employers) for their employees in the form of Employees’ Pension Funds or by the National Pension Fund for those who are self-employed in which the government is the insurer. The Employees’ Pension Funds unlike in Malaysia are operated employers and a large portion of them comes from the Employees’ Pension Insurance. This Employees’ Pension Insurance is the core of the income security for the old age and all workplaces with more than five employees are required to participate in this scheme. The premium has to be contributed both by the employers and employees based on income. Whereas Pension System for civil servants is called Mutual Aid Pensions which covers both Basic Pension; the first tier and the income-related; the second tier. In summary, the entire adult population of Japan is covered either by the Basic Pension and added by either Employees’ Pension Insurance or the National Pension Plan for Public Sector and the Mutual Aid Pensions for Private Sector.

There are other types of personal pensions by private insurance corporations and trust banks, however they do not fall under this category of a social security system and thus will not be discussed in this paper. A number of reforms have taken place in line with changing life-styles and continuing recessions of global economy affecting Japan. Currently 83.9% of Japanese corporations offer retirement packages for their employees. This package can be either in the form of one time lump-sum payment or a life-long or limited duration of payment.

The Long Term Care Insurance which is particularly designed to support for old age independence is user-oriented social insurance system. This provides coverage of comprehensive health, medical and welfare services. As stated above it is compulsory for those above the age of 40 years old to get insured. The insurers are those who have been engaged in health and welfare services for the elderly and expected to deliver services in harmony with the community’s social values. They play the role of collecting the insurance premiums, managing the fund, assessing the care needed and settling the payments to service providers. Hence they work with the government, prefectures, medical and pension insurers. There are two categories of the insured; (i) those who are aged 65 and above; Category I and (ii) those who are 40 to 64 years old; Category II. Premium is based on income and there are measures to lessen the burden of low-income persons. Premium is deducted from pensions for Category I and from health insurance for Category II. The cost incurred in this Insurance is borne 50% by premiums and 50% by public expenditure.

There are different layers of social security provided for older people and yet the social security system in Japan has to undergo a number of reforms to meet the evolving needs and challenges faced by the older people in the country.

Social Safety Net for Older People in Singapore

Singapore has a similar system of social safety net and it is called the Central Provident Fund (CPF). The main objective of this scheme is to provide protection during old age and it is governed by the Central Provident Fund Act (CPF Act). It has been amended several times since 1968 to ensure achieving the objective in the changing of social status. Similar to Employee Provident Fund (EPF) in Malaysia, it is managed by a Board comprising of representatives from the government as well as employees and employers. The Board has investment powers and administers the scheme and manages the collection and distribution of funds. The financial statements of the Board are to be submitted to the Parliament and members have the right to sue the board for breach of their duty or mismanagement of the fund.

Under section 7(1) and 13(A) (1) of CPF Act, CPF covers all Singaporeans as well as Permanent Residents as long as they are working in Singapore. Singapore promotes self-reliance and work ethic and the system is self-funding with individual savings built up through the person’s own contributions. The contribution is credited into three accounts as follows:

- Ordinary Account (OA) – Savings under this account are to be used for property purchase, investment, education and insurance premiums for home protection and dependent protection etc.

- Special Account (SA) – Savings under this account are to be used for retirement purpose and investment in retirement related financial products.

- Medisave Account (MA) – Savings under this account are for healthcare expenses and approved medical insurance.

Employee Provident Fund (EPF) in Malaysia unlike in Singapore consists of two accounts; Account 1 and Account 2. Account 1 comprises 70 percent of members’ savings which can only be withdrawn when reaching the retirement age; currently is 55 which means members can withdraw all their savings at the age of 55 years old. The drawback of this system is that members usually withdraw all their money from this account at the age of 55 and used it up with 3 to 5 years. Hence, there will not be any saving left for retirement and ends up in poverty. Hence a person may work whole life and yet can be poor during the retirement if the person used up all their savings. Whereas Account 2 under EPF comprises 30 percent of members’ savings, where members can make pre-retirement withdrawals aimed at enhancing members’ retirement well-being. The savings in this account can be withdrawn for housing, education, medical, performing Haj or when a member reaches the age of 50 years old to prepare for retirement of when the saving is more than 1 million. The main difference between Malaysia and Singapore is that Malaysia does not have Medisave Account (MA) as practised in Singapore. Another difference is that under CPF in Singapore, the minimum sum is determined to provide for a basic standard of living in retirement unlike EPF in Malaysia, the majority withdraw the whole amount of money at the age of 55. CPF saving under the Minimum Sum Scheme is designed to provide a monthly pay out for around 20 years. Though EPF in Malaysia also have the same arrangement, most Malaysians choose to withdraw all the money at the age of 55 instead of monthly withdrawal and hence there is the issue of poverty at the old age. In this regard, there should be more awareness of the importance of old age savings in Malaysia and encouragement to withdraw monthly.

Findings and Recommendations

Retirement is an increasingly active phase of life where people should be taking personal responsibility for their own wellbeing by working, saving and looking after their health. If they have opportunities to continue contributing to society by working longer or volunteering in their communities, they should be doing so.

EPF was set up to provide coverage for people at their old age; it does not seem to fulfil the purpose. Sixty nine percent of EPF members aged 54 in 2013 are found to have savings below RM50,000.[i] 50% of retirees have exhausted their EPF savings within 5 years. The majority of members have withdrawn their savings at the age of 55[ii] before actually retiring at the age of 60. Research also found that roughly about 70 percent of people who withdraw their retirement savings in full will essentially deplete the money within three to five years’ time. It is recommended that a minimum of RM196,800 should be left in the saving upon retirement, however, statistics showed that only 22 per cent of active 54 year old contributors met this minimum.[iii]

EPF has introduced a number of initiatives to assist members to increase their savings and discourage members from depleting all their savings in a short period of time. Under these new initiatives, members are encouraged to increase their savings in Account 1 from 60% to 70%. EPF also introduced the Age 55 Years Withdrawal, a flexible withdrawal facility that gives members the option to withdraw their savings lump sum or monthly, partially or a combination of the options and extended the contribution (mandatory) age from 55 to 75 for members who are still in employment. In January 2014, EPF revised the Basic Savings, setting RM196,800 as the minimum amount members should have in their EPF accounts when they reach age 55.

Despite all these efforts by the EPF, research found that Malaysians do not have enough savings for their old age. Since the fund is compulsory only for those under employment and based on the income contributed by the employers and the employees, the unemployed and the self-employed are not covered by this saving scheme. And hence the unemployed and the self-employed are left with no social coverage unless they have savings on individual basis. Even those who have EPF savings tend to use up their savings within the first few years of withdrawal and this result in no social safety net for them.

It is evident that EPF savings alone are not sufficient for a person to cover their old age. These insufficient savings for old age are as a result of a number of reasons; longer lifespan, low salary, early retirement, paying children’s tertiary education fees and changing of social and economic trends and national development. Even if an individual with high salary having big EPF savings may be left with a little amount of money at their old age since most of them have used up the savings for the education of their children. Hence children’s education is one of the main factors in depleting the EPF savings for the old age. In addition to this, there is no other saving scheme like insurance based savings like in Japan unless it is initiated by an individual himself. Most of the time, people are unaware or do not realise the importance of savings for the old age. This factor is very crucial to those who are in the middle and lower income groups. Hence, accessibility to education is a very important factor.

Hence in addition to the current practice of EPF, there should be an additional layer of social security scheme for old age by introducing savings based on insurance principles, something equivalent to what Japan has introduced to strengthen the social safety net for old age. At the same time, the government needs to create more awareness on the importance of savings for the old age.

If insurance system is introduced, every individual who can afford will be covered under the insurance and this in turn will reduce the burden on the government and the government can provide a better quality service to those who are really in need. Thus, this will reduce the burden on the government and at the same time, it guarantees a better life for those who are vulnerable. There should be improvement in recruitment and retention of an aging workforce since working longer can benefit individuals, business, society and the economy. Thus, government should set out new actions to ensure that older people can work and it involves challenging outdated perceptions and making the case for older workers within the business community.

Pension age can help support the financial, health and social well-being of individuals into later life. It is important for the economy of the country, for employers and for individuals to make sure that old aged people can continue to afford pensions. Retiring at 55 instead of 65 could reduce an average earner’s pension pot by a third- they would also have to spread this over a much longer retirement. By raising the pension age, it will help maintain a sustainable balance between the proportions of workers and retired people. We also have to remove the default retirement age, so in most cases employers can no longer force employees to retire just because they reach the arbitrary age of 65. Another way is helping older people get online to ensure that older people are not left behind and are able to benefit fully from the increased independence that comes with digital competence.

Since EPF is based on income contribution from employees and employers, those who are not working are normally not covered under this scheme. Though the government has introduced 1 Malaysia Retirement Savings Scheme for this group of people, it is on voluntary basis and the participation is very low. Hence there should be one basic saving scheme that covers all citizens regardless of their employment status.

In summary, it is recommended to introduce the followings to strengthen the current social safety scheme in Malaysia:

- Universal Basic Pension Plan: To make mandatory to all those above the age of 18 to be registered into a Basic Saving Plan like what Japan has introduced for all their citizens. With this plan, nobody will be left out from the social safety net for old age.

- Insurance Based Saving: This plan will be an additional security measure in case there are no sufficient savings in EPF or the amount in EPF has been exhausted before the old age.

Introducing the above schemes into the existing social safety net will assist in lessening the burden on the government in providing assistance to older people and improve the quality of assistance provided to those needy people.

Conclusion

Malaysia may be headed for a retirement crisis as tens of thousands of Malaysians depart the workforce for their golden years with less saving than is needed to keep them out of poverty.[iv]

[i] EPF savings and your Retirement by EPF.

[ii] EPF Annual Report 2014.

[iii] Malay Mail Online News Portal, EPF may realign withdrawal age closer to 60, dated 10th April 2015.

[iv] Malay Mail Newspaper, Retirement crisis brewing as EPF savings suggest pensioner poverty, dated 5th October, 2014.

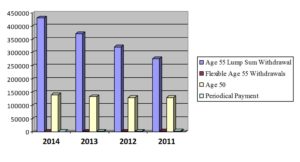

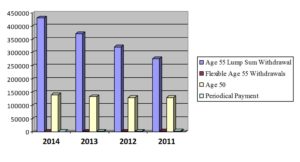

Breakdown of EPF withdrawals for the year 2014[i]

Based on this statistic, it can be seen clearly that most members opted for withdrawing the whole sum of savings at the age of 55 and the percentage of withdrawal has been increased in recent years. Only less than 1% has opted for periodic payment over the years. Based on the Annual Report of EPF 2014, the majority of the members have an average savings of less than RM167,000 which is lower than the minimum saving level set by EPF at RM196,800. It is more alarming to find out that 69% of the members have less than RM50,000 in their account and only 31% of the members are still at work at the age of 54. Only 54% of the members have less than RM20,000 in their account and evidently this amount of savings is not sufficient to support for 20 years after the retirement. In summary, most Malaysians do not have sufficient savings for their old age.

Currently only about 10 to 20 percent of Malaysians are considering non-mandatory retirement savings and investments to be added as a safety net for their old age in addition to their EPF contributions. EPF has implemented measures to enhance members’ savings for their old age by increasing the mandatory contribution, introducing the PRS (Private Retirement Scheme) in 2012 as a voluntary long-term investment scheme for old age and encouraging members to opt for flexible Age 55 withdrawal to choose partial or a monthly payment to lump-sum withdrawal of the savings. Still all these measures are not sufficient to shield the Malaysians during the old age and hence it is strongly recommended to introduce an insurance scheme of savings like in Japan as an additional social safety net to strengthen the existing social safety net for old age in Malaysia. In addition to this, minimum wage should be increased and retirement age should be increased to 65 years old in view of increasing life expectancy and living cost.

[i] Data collected from 2014 EPF Annual Report.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

References

- Asher, M.G., 2002. Southeast Asia’s social security systems: Need for a system–wide perspective and professionalism. International Social Security Review, 55(4), pp.71-88.

Google Scholar

- Asher, M.G. and Bali, A.S., 2014. Financing social protection in developing Asia: Issues and options. Journal of Southeast Asian Economies (JSEAE), 31(1), pp.68-86.

Google Scholar

- Asher, M. and Bali, A.S., 2015. Public pension programs in Southeast Asia: An assessment. Asian Economic Policy Review, 10(2), pp.225-245.

Google Scholar

- Donghyun Park (Edit.) Pension Systems and Old-Age Income Support in East and Southeast Asia: Overview and Reform Directions, (2012), ADB.

Google Scholar

- Employee Provident Fund (2014), 2014 Annual Report, Malaysia.

- Gruber, J. and Wise, D.A. eds., 2009. Social security programs and retirement around the world. University of Chicago Press.

Google Scholar

- Holzmann, R., 2015. Old-Age Financial Protection in Malaysia: Challenges and Options, World Bank Group, Washington DC

- Holzmann, R., 2000. The World Bank approach to pension reform. International Social Security Review, 53(1), pp.11-34.

Google Scholar

- Holzmann, R., 2005. Old-age income support in the 21st century: An international perspective on pension systems and reform. World Bank Publications.

Google Scholar

- Ministry of Finance, Economic Report 2015/2016, Malaysia.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2002. Towards Asia’s sustainable development: the role of social protection. OECD Publishing.

- Sri Wening Handayani and Babken Babajanian (Edited), Social Protection for Older Persons: Social Pensions in Asia (2012), ADB

- Teh, J.K.L., Tey, N.P. and Ng, S.T., 2014. Family support and loneliness among older persons in multiethnic Malaysia. The scientific world journal, 2014.

Google Scholar

- Yew, S.Y., 2014. 3 Malaysia’s Employees Provident Fund and social security. Asset-Building Policies and Innovations in Asia, 3, p.38.