Discussion

Intussusception occurs when the proximal segment of an intestine (the intussusceptum) telescopes into the lumen of the adjacent distal segment of an intestine (the intussuscipiens) (1). The most common classification of intussusception is according to the anatomical location, which is divided into four categories: enteric, ileocolic, ileocaecal, and colonic (1). (Enteric and colonic intussusceptions are those that are confined to the small and large intestines, respectively. Ileocolic intussusceptions are defined as those with the prolapse of the ileum through the ileocaecal valve into the colon, whereas ileocaecal intussusceptions are defined as those with the ileocaecal valve as the lead point for the intussusception (1).

Adult intussusception is only 1% of all intestinal obstructions, and it presents with a variety of symptoms, most often consistent with bowel obstruction (1). Symptoms are divided into acute, intermittent, or chronic according to Azar et al. (1). Acute intestinal obstruction is not common, whereas most patients present with subacute, chronic, or intermittent symptoms (2,3). The classic clinical triad of abdominal pain, palpable sausage-shaped mass, and haeme-positive stool is rarely present (7). The mean age of presentation is around 50—60 years old. Male to female ratio is 1:1.3 (2).

Demonstrable etiology is found in up to 90% of adult intussusceptions (7). Azar et al. reported a large series of 58 cases of adult intussusception, where he found that up to 46% are due to underlying large or small bowel malignancy. Of all the benign causes, nearly half are secondary to postoperative adhesions. There are lead points thought to be either the suture line of a previous enterotomy or an adhesion (1). Benign polyps account for almost 25% of cases of adult intussusception, and the most common benign lesion is lipoma (6).It is therefore very difficult to distinguish between benign and malignant lesions as a lead point of an intussusception from either clinical presentation or imaging modalities, and also it is difficult to distinguish between them intraoperatively (1, 2, 7). Lipoma accounts for up to 4% of all benign tumours of the intestine and is generally asymptomatic (3). It is the most common benign nonepithelial tumour of the colon, especially around the ileocaecal valve, and is generally submucosal and may protrude through the lumen, though it may also be of subserosal origin (4). Lipomas are found incidentally in 0.3%—0.5% of autopsies (3). (3) Although the majority are asymptomatic, lesions more than 2 cm tend to cause symptoms such as pain, change in bowel habits, and rectal bleeding (5). A literature search found several case series of small and large bowel lipomatous polyps causing intussusception in adults (2, 3, 6). It was estimated that intestinal lipomas cause approximately 8% of all adult intussusceptions (1, 3).

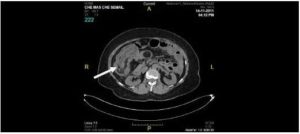

Several imaging modalities have been used to diagnose intussusception. Takeuchi et al. report that Computer Tomography (CT) Scan proved the most accurate modality to diagnose intussusception followed by ultrasonography. CT scan has a yield of 52% as compared to a yield of 32% for ultrasonography (2, 7). Gastrointestinal contrast study is comparably useful with a yield of 41% but is not advocated in most cases of complete intestinal obstruction (2). Khan et al. quoted a diagnostic accuracy of CT scan of around 80% in diagnosing intussusception. Based on these results, Takeuchi et al. report that CT scan may be the first examination in a patient for evaluation of abdominal masses and nonspecific abdominal pain where intussusception is a possibility (7). The classical finding of a CT scan includes a target lesion or sign which represents the outer intussuscipiens and the inner intussusceptum, which is clearly visualized due to edematous bowels, otherwise also known as “double ring” or “coiled spring” appearance (2, 7). On CT scan, an intestinal lipoma will appear uniformly hypodense with absorption densities of ”’80 to ”’120 Hounsfield units (fat composition) (5). Ultrasonography has been used to evaluate suspected intussusception in both children and adults. The classical features include the “target” or “donut” sign on transverse view and the “pseudokidney” sign on longitudinal view (7). As up to 90% of adult intussusceptions are due to underlying lesions, CT scan is more superior to ultrasonography in detecting such lesions (2). As in our case, CT scan has accurately revealed the presence of intussusception and was able to visualize the underlying lipomatous polyp as the lead point.

Despite proper work-up with various imaging modalities by several authors, such as ultrasound, contrast studies, and computer tomography (CT) scan (1, 2, 3, 6, 7) and lower gastrointestinal endoscopy (2), it was still inadequate to confirm the diagnosis of benign lesion preoperatively (1). Furthermore, Mandal et al. and Azar et al. both agree that it is difficult to differentiate intraoperatively a colonic lipoma from malignancy in a case of intussusception (1, 3). This gives rise to a surgical dilemma in terms of operative approach. In this case, even though CT scan was able to provide us with adequate information regarding the etiology of intussusception, intraoperative findings appear to warrant strong suspicion of malignancy, as supported by Khan et al. and Mandal et al.

Although the optimal treatment for adult intussusception is slightly controversial, it is well agreed by most authors that surgical intervention is unavoidable (1, 2, 6, 7). Operative approaches are divided according to the most possible etiology, based on patient’s medical history and intraoperative findings (1).

In cases of intussusception secondary to postoperative enterotomy or adhesion, manual reduction without bowel resection is feasible provided that bowels are viable (1). In cases where bowel wall is inflamed, ischaemic, or friable, it is advisable not to attempt manual reduction but to proceed directly with resection as it associated with increased risk of spillage or undetected mucosal necrosis leading to delayed perforation (7).

All obvious small and large bowel lesions require resection to prevent recurrence of intussusception. Majority of authors recommend resection of bowel without attempt of intraoperative manual reduction as this reduces the risk of inadvertent perforation during reduction and allows uninjured healthy bowel to be used in anastomosis (1). Another reason against intraoperative reduction is that there is a higher incidence of malignancy of both small and large bowel origins, as mentioned earlier. Reduction of malignant lesion increases the risk of intraluminal seedlings and venous embolization of malignant cells (6,7). More importantly, the lesion at the lead point may escape detection (2). Chronic intussusception may be difficult to reduce due to cross-scaring between intussusceptum and intussuscipiens (2). However, another view holds that reduction of intussusception as much as safely possible followed by appropriate resection preserves bowel length in order to avoid short gut syndrome (2). Khan et al. and Takeuchi et al. agree that reduction of small bowel intussusception is feasible only if a preoperative diagnosis of benign etiology is confirmed and bowel is viable (6,7). As it is discussed earlier however, preoperative confirmation of benign or malignant lesion is rarely achieved.

Colonic lesions causing intussusception–ileocolic, ileocaecal, and colocolic types–are associated with high incidence of malignancy, especially if aged over 60 year old (6,7). Complete resection without attempt of reduction is advocated by most authors (1, 6, 7). Azar et al. recommend adequate resection of the lesion, including resection of the lymphatic drainage with the intent of oncological clearance as for malignancy (1).

Our patient presents with acute intestinal obstruction secondary to ileocolic intussusception, with preoperative CT scan confirming the intussusception and identifying the lead point as a polyp with features suggestive of lipoma. However, intraoperatively, with the presence of nonviable large and small bowels, and the presence of suspicious caecal polyp with ulcerative lesions in the caecal mucosal wall, decision was made to proceed with a right hemicolectomy without manual reduction in view of possible malignancy. End-to-end anastomosis on healthy bowel reduces the risk of anastomotic leak.

Conclusion

Intussusception in adults is a different entity from children; therefore, it warrants a different approach in management. It is not a common cause of intestinal obstruction, but a high index of suspicion is necessary especially if patients present with subacute or intermittent symptoms. As overwhelming majority of adult intussusceptions is due to an underlying pathology, preoperative CT scan is advisable for diagnostic purpose and preoperative planning. Intestinal lipoma is a cause of intussusception, and it is difficult to differentiate it from malignancy neither preoperatively nor intraoperatively. Most authors advocate for segmental resection without attempt of manual reduction and proper resection of the lymphatic drainage in view of high incidence of malignancy. All adult intussusceptions with a demonstrable lesion detected preoperatively or intraoperatively should be regarded as malignancy until further confirmation by histopathological examination.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Dr. Mohd Nor Gohar Rahman, Head Department of Surgery.

References

1) Azar, T. & Berger, D. L. (1997). “Adult Intussusception,” Annals of Surgery 1997 Aug; 226 (2):134-8.Publisher – Google Scholar

2) Rathore, M. A., Andrabi, S. I. H. & Mansha, M. (2006). “Adult Intussusception — A Surgical Dilemma,” J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad 2006;18 (3)

Publisher – Google Scholar

3) Mandal, S., Kawatra, V., Dhingra, K. K., Gupta, P. & Khurana, N. (2010). “Lipomatous Polyp Presenting With Intestinal Intussusception in Adults: Report of Four Cases,” Gastroenterology Research – 2010; 3 (5):229-231

Publisher – Google Scholar

4) Marra, B. (1993). “Intestinal Occlusion Due to a Colonic Lipoma. Apropos 2 Cases,” Minerva Chirurgica 1993; 48 (18):1035-1039.

Publisher – Google Scholar

5) Melzer, E., Holland, R., Dreznik, Z. & Bar-Meir, S. (2000). “Unusual Presentation of Colonic Lipomas,” IMAJ2000;2:780—781

Publisher – Google Scholar

6) Khan, M. N., Agrawal, A. & Strauss, P. (2008). “Ileocolic Intussusception – A Rare Cause of Acute Intestinal Obstruction in Adults; Case Report and Literature Review,” World Journal of Emergency Surgery 2008, 3:26

Publisher – Google Scholar

7) Takeuchi, K., Tsuzuki, Y., Ando, T., Sekihara, M., Hara, T., Kori, T. & Kuwano, H. (2003). “The Diagnosis and Treatment of Adult Intussusception,” Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology 2003; 36 (1):18—21.

Publisher – Google Scholar