Introduction

Clusters are interconnected companies and local institutions (or national as well), aiming to increase competitiveness, increase innovation, and new working places. Clusters, by the specificity of their character, combine regular business operations, local government agencies and scientific entities, thus contributing to the rapid growth of local economies. They also allow many small and medium-sized companies operating locally to start international activities. Therefore, they constitute the right business environment, which drives economic growth. The clusters are present in most national economies, but they reach various stages of development in different economic conditions.

The shape of the clusters is affected by several factors connected with the location and nature of associated companies. Therefore, it is not possible to create two identical clusters. Even a group created by the same corporation in different markets will never be the same. Cooperation and competition at the same time give the possibility of shaping the company competitiveness, raising its level through the continued development and improvement of processes in the units. The cluster can increase the attractiveness of an investment location, which leads to a better competitive position among the regions. Clusters help to increase the innovation of the associated units, to create new products, new companies and new jobs. The clusters combining the activities of entrepreneurs, local government institutions and research units contribute to the dynamic growth of local economies.

One of the more common definitions of clusters is that formulated by Porter, according to which clusters are “geographic concentrations of interconnected companies and institutions in a particular field, linked by commonalities and complementarities”. Clusters include linked industries and other entities (suppliers), distribution channels and customers (demand), related institutions (research organization, universities, training entities, etc.) (Porter, 2001). A cluster is a set of interdependent organizations that contribute to the realization of innovations in an economic sector or industry (Preissl 2003). In the UNIDO context, a cluster is understood to refer to a sectoral and geographical concentration of enterprises and/or individual producers that produce a similar range of goods or services and face similar threats and opportunities (What are clusters…).

By simplifying the definition of clusters, it can be assumed that (1) a cluster is a group of affiliated companies operating in the same geographic region; (2) there are market and non-market relationships between companies, as well as formal and informal ones; (3) cluster development is closely related to the competitiveness of the enterprise and the region in which it operates.

Due to their dynamic nature, there are many types of clusters, divided according to different criteria. According to Enright (2000), there are five different types of clusters:

- working clusters – associated companies utilize a critical mass of expertise, local knowledge, human resources and resources arising from the location to compete with other firms outside the cluster. Various cooperation takes place between the companies of the cluster and quantitatively there is more of it in relation to the companies from outside the cluster. They attract investors, resources and skilled workers to the region;

- latent clusters – existing critical mass is sufficient to reap the partial benefit of belonging to a cluster. However, there is no developed interaction and flow of information among its participants, which are necessary for the extensive use of the location and operation of the group of companies. This situation is often caused by the lack of knowledge of other participants in the cluster, the lack of common purpose and vision, and the absence of mutual trust between entities. In this case, individuals do not think of themselves as participants in the cluster and consequently do not use the opportunities offered by cooperation;

- potential clusters – in this type of connection, it is reasonable and possible to develop the cluster, but it must be deepened and extended to the efficient use of the location. There are often gaps in the contacts and exchange of information, which is essential for the development of the cluster. There is no awareness of the hidden function of the cluster, but factors are demonstrating the presence of connections;

- policy-driven clusters –governments choose a cluster to support and develop, but there is no critical mass and conditions favourable to economic development. However, clusters are created by political decisions and are financed by the government. It is based on the assumption that the government can create a cluster on any terrain, regardless of the economic analysis;

- wishful thinking clusters – there is a lack of all the factors of cluster development; there is no critical mass and no benefits for economic development.

An interesting classification of clusters was made by Ketels who divided the clusters into industry groups (e.g. pharmaceutical, automotive etc.), but also drew attention to the perceived location of the market and dependence on the model of business. Ketels distinguished:

- local industries – clusters associated with a local recipient, whose location is determined by geographical proximity to major customers of companies associated in clusters. This type of clustering caters only to the needs of local markets. Clusters of this type are created to improve the competitiveness of products, but have a little effect on the business localization patterns in the region;

- natural resource-dependent industries – clusters associated with the local resources which attach the company to a specific location. It meets the needs of the global market, but due to the nature of the region, companies are forced to function in the cluster;

- traded industries – clusters focused on trade, in which the companies are free to form units that produce goods for the international market. In these clusters, the location does not matter, and their creation in a specific region is a decision of business community and cluster initiatives. High stability characterizes this type of cluster and their presence is a crucial aspect of the attractiveness of the location (Ketels, 2003).

Activities of clusters are visible in the region in which they are located. The following effects can be indicated: the creation of new jobs; attraction of foreign direct investment; structural changes in the region; economic development of the region; emergence and development of specific factors of production, both in the electronic and automotive industry; creation of innovation culture and development of entrepreneurship in the region; development of large-scale production network consisting of specialized suppliers and subcontractors; creation of an attractive labour market, attracting skilled workers, changes in the local labour market; increasing in the share of exports from the region..

Cluster Policy – Theoretical Approach

Cluster policy can be understood as a set of instruments supporting the creation of strong bonds between enterprises, science and local institutions occurring in a given territory. It is usually an element of innovation policy, but also of industrial policy and a broad development or economic policy. Foster linkages between cluster stakeholders can see the role of cluster policy; build relationships between companies and institutions; facilitate joint programs building; encourage trust-building and support the cluster’s institutional network. Policies supporting clusters can be divided into three categories based on motivations and policy objectives. The first type is the most horizontal model concerns “facilitating policies”. In this case, the local government is focused on creating favourable microeconomic business conditions for growth and innovation that indirectly stimulate the cluster growth. A second type is connected more with “traditional framework policies” like industry policy, research and innovation policy and regional policy. The last category is “development policies” aiming at creating, mobilising or strengthening a particular cluster and sectoral cluster initiatives and this type of policy can be named as a pure cluster policy (The Concept of Clusters).

A cluster policy character can be described by:

- Cluster development policies directed at creating, mobilizing, or strengthening a particular cluster, e.g. a national funding competition for the best life science cluster strategies.

- Cluster leveraging policies that use a cluster lens to increase the efficiency of a specific instrument, e.g. an R&D subsidy provided only to companies in regional clusters where the subsidy is likely to incur spill-over effects beyond the recipient firm.

- Cluster facilitating policies directed the elements of the microeconomic business environment to increase the likelihood of clusters to emerge, e.g. regional or competition policies that remove barriers for competition between locations (Cluster policy in Europe).

The models of the cluster policy can be classified according to the different levels of economic development of the country in which the model exists. The type of the cluster support activities depends on the political structure, size and resources of a country (Boekholt P., Thuriaux B., 1999). The difference in models, depending on the level of development, may apply to various aspects of such a policy (Uyarra E., 2014): understanding the role of the clusters and the clusters themselves (cluster definition); the scope of the policy and level of policy formulation (national, regional or local policy); policy objectives (subjects) (industrial areas, industries, specific groups of companies); principles of identification and selection of clusters to be supported; institutional forms of cluster operation; instruments used for support, and the moment or period of cluster support.

There is a different approach to cluster policy implemented in various countries (see figure 1). In some countries, it can be noticed that the government offers a dedicated support program for the cluster as a part of its policy to create stronger linkages between units. This situation can be seen in Korea, Catalonia, Mexico and Poland. On the other side, there are countries with strategic cluster-based policy, where they use clusters and networks as organizational infrastructure for policy action. In this group, Germany, France, Basque can be found.

Figure 1: Various models of cluster policy

Figure 1: Various models of cluster policy

Source: author’s own work based on Ketels Ch. (2016) in: M. D. Nielsen, Supporting Clusters Interregional Collaboration-Status and Moving Ahead, www.clusterexcellencedenmark.dk [access 15.12.2019]

Clusters and cluster policy in Germany

Relying on the German data from the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy in Germany there were 90 clusters (as of March 2020), which were characterized by a formal character and efficiently worked for their members and recipients.

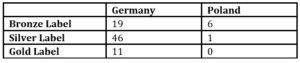

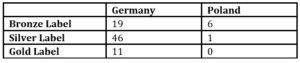

According to the European Cluster Excellence Initiative, there were 19 Bronze Label clusters in Germany, 46 Silver Label certified clusters and 11 Gold Label clusters. German clusters have been around for many years, and their average age is much longer than in other countries, especially Eastern European and Asian. It can also be noted that German clusters are less numerous than other such connections because the key is the degree of involvement of cluster entities. In essence, companies can be treated as cluster actors only when they commit to co-create the cluster (often such an obligation has a written form in which the company undertakes to pay membership fees, which allows the elimination of artificial clusters). A characteristic feature is also the broad geographical coverage of German clusters, which includes entities located in various, often distant regions. In German clusters, more than half of the entities are companies from the SME sector, and the share of research and development units is about 15%. Clusters have a high degree of formalization of tasks divided between participants, and their operation is formalized and based on association agreements (Meier zu Köcker, Garnatz, 2012).

Clusters in Germany can be combined with development, innovation and technology policies. They are monitored because they are perceived as driving elements of the local economy.

In Germany, the first public grant program focuses on the clusters support, and to strengthen it, 25 regional developments were established in 1995 followed by general nationwide programs to support businesses. Cluster policy in Germany has a rather central character and aims to build a bridge between business and science to achieve economic growth and a higher level of innovativeness. The primary instrument is the financial support (e.g. 1.2 billion EUR worth support combined of public and private funding in the cluster program called Leading-Edge Cluster competition). However, the main idea, and at the same time quite innovatory, is to support the connection between not only different industries but various companies if we look at the size of firms (connect huge, transnational corporations with freshly established starts-up).

Cluster support activities take place at two levels in Germany – at the national and federal level (federal states). A comprehensive strategy has been developed at the federal level to cover clusters under the “high-tech strategy”. The assumptions included both activities targeted at SMEs and modular activities on a local scale, taking into account new technological solutions and promoting the most efficient clusters. The essential initiatives supporting clusters at the federal level in Germany:

- Cluster Competition- the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF),

- “Network management” module as part of the Central Innovation Program

- The „go-cluster” programme provides a stimulus to improve cluster management and help turn German clusters into highly effective international clusters. This program aims to support the transformation of the most efficient national innovation clusters into global clusters of excellence; promote new cluster services to stimulate cluster managers to offer new services; increase the international visibility of participating innovation clusters and analyse trends of international cluster policy to work out recommendations for the German perspective (The German programme).

The federal states, on the other hand, have various ways to support networks and clusters. They can direct their help to specific industries and fields of technology. The local authority can determine the relationship with the economic support provided by a given Land, as well as to engage in activities of entities from outside the given Land (Meier zu Köcker, Garnatz, 2012). All of the 16 federal states have launched numerous measures to support the development of efficient clusters – across technology, business or innovation. The cluster support at the federal level provides financial help for cluster management, innovation projects, educational activities and joint public relations initiatives (Clusterplattform).

Clusters and cluster policy in Poland

It is challenging to provide the number of clusters in Poland because some of the registered clusters do not meet the definition conditions and do not function daily. It can be assumed that there are about 150 clusters and cluster initiatives, of which about 50 are operational. According to the European Cluster Excellence Initiative in Poland (as of 18.03.2020), there are 6 clusters labelled Bronze Label, only one was qualified to the Silver Label group. In contrast, no cluster received the Golden Label (one Polish Silesian Aviation Cluster cluster was in this group until February 15, 2020).

Clusters found themselves as one of the pillars of the Polish economic development plan, which was named Responsible Development Plan and was announced in 2016 (see figure 2). The objectives of the government for 2020 (extended till 2030) include an increase in investment to over 25% of the GDP; increase in the share of R&D expenditure to 2% of the GDP; increase in the number of medium-sized and large enterprises to over 22 000; more Polish foreign direct investment (increase by 70%); growth of industrial production exceeding the GDP growth; GDP per capita of Poland at the level of 79% of the EU average (Responsible Development Plan). Clusters, together with industrial valleys, are in the target audience called reindustrialization. According to the plan’s assumptions, industry is a natural environment for innovation and the core of expenditure for research and development. Innovative companies create necessary cooperation chains and high-quality jobs. The challenge for the next years is to support the existing and develop new competitive advantages and specialisations. Clusters are therefore in the centre of interest of national authorities because they combine both the process of creating innovation through close cooperation of companies and create jobs through an increased degree of industry concentration in a given region.

Figure 2: Five pillars of the economic development of Poland

Source: based on the Responsible Development Plan, https://www.gov.pl/web/fundusze-regiony/plan-na-rzecz-odpowiedzialnego-rozwoju [access 7.03.2020]

Cluster policy in Poland results in a way from European policy and is carried out in similar time horizons, which is most often the result of the functioning of EU budgets. Assumptions for current activities have been included in such documents as National Development Strategy until 2020, Enterprise Development Program for 2020 and Directions and assumptions of cluster policy in Poland by 2020. In the National Development Strategy until 2020, clusters are perceived as a factor improving the country’s competitiveness and deepening regional specialization. In this document and many others, clusters are to constitute an essential lever for the development of Polish exports, both in traditional and modern industries, such as ICT or automotive. The task of active cluster policy will be, inter alia, to support the most innovative and showing the highest potential for the development of Polish clusters that are able to create highly-competitive products and services constituting Polish and European export specialties (Jankowiak, 2019).

The principal aim of the Polish cluster policy is to strengthen the innovativeness and competitiveness of Polish economy through intensified cooperation, interactions and knowledge transfer (that is through providing support for existing and newly created clusters) as well as through supporting the development of vital economic specializations (that means selecting critical national and regional clusters and focusing part of public support on them).

The achievement of the principal aim involves the fulfilment of the following specific goals (Lindqvist, Ketels, Sölvell, 2013):

- stimulation of internal interactions, knowledge transfer and cooperation as well as the creation of necessary social capital;

- expansion of the external networking of clusters and entities operating within them, especially in a cross-sector and international dimension,

- strengthening of joint and integrated strategic planning processes within clusters,

- increase of the number of innovative goods and services offered on domestic and international markets by companies and entities operating within clusters, which should lead, among other things, to the growth of export,

- mobilization of private investment in clusters, including the creation of new companies and inflow of foreign investment as well as increasing private spending on R&D and innovation-oriented activities,

- the development of the ecosystem of supporting institutions (e.g. education and research institutes, technological parks and technology transfer centres, etc.) and better customization of their offer and activities to the needs of companies operating within the clusters,

- boosted the effectiveness of using public funds by their concentration and obtaining synergy between different policies and support instruments (e.g. concerning infrastructure development, human capital, R&D, promotion, internationalization, etc.).

According to the assumptions adopted by the Working Group on Cluster Policy, the main goal of cluster policy should be to strengthen the innovation and competitiveness of the Polish economy. It should be done based on the intensification of cooperation, interaction and knowledge flows within clusters and supporting the development of strategic economic specializations (Key National Cluster). Key National Cluster in Poland is a cluster of significant importance for the national economy and high international competitiveness. Key National Cluster is identified at the federal level, including based on criteria regarding critical mass, development and innovation potential, past and planned cooperation as well as statement and potential of the coordinator. In Poland, there are currently 16 vital national clusters that have been selected in the national competition. The Organizer of the Competition for the status of the Key National Cluster (KNC) is the Ministry of Development, which runs the Competition in cooperation with the Polish Agency for Enterprise Development (Jankowiak, 2019).

Comparison and conclusions

Comparing both clusters and cluster policies in Germany and Poland, many differences can be pointed out. It can be assumed that the development of clusters in Germany and, consequently, the implementation of cluster policy is a process started much earlier than in Poland. Hence the experience and achievements of both countries are varied. Although the number of clusters in Germany is smaller than in Poland, they are characterized by a higher degree of formalization, which can be assumed that the number of actually operating clusters in Germany is higher than in Poland. It is also shown by the European Cluster Excellence Initiative (table 1), which awarded more distinctions to German clusters than Polish ones. This may mean that German clusters are at a more mature stage of their development.

Table 1: European Cluster Excellence Initiative in Germany and Poland

Source: Author’s work based on The European Secretariat for Cluster Analysis (ESCA), available at https://www.cluster-analysis.org/ [date of entry 20.03.2020]

Source: Author’s work based on The European Secretariat for Cluster Analysis (ESCA), available at https://www.cluster-analysis.org/ [date of entry 20.03.2020]

Cluster policy in Germany was created in the 1990s, i.e. a decade earlier than cluster policy in Poland, hence it is at a different level of development (Table 2). In both countries, there are units dedicated to cluster policy, but this is not their only task – only one of the areas of activity. On the one hand, this is the right thing to do, as in both cases cluster policy is part of broad innovation policy, but the lack of specialized cluster units can lead to a reduction in the scale of cluster policy. In Germany, most cluster support programs operate at the national level, and only two are regional programs. The opposite situation occurs in Poland, where local programs dominate (22 programs). It can be interpreted that in Poland clusters are more local initiatives while in Germany are seen as a national instrument. However, regional cluster support programs in Poland are not financed from regional sources, but national and European sources. In Germany, on the other hand, funding for regional programs is funded through regional sources.

The cases of cluster policy in Germany and Poland examined in the article show that there are no significant differences in the assumptions and implementation of these policies in both countries. It can be assumed that due to the long-term nature of the clustering process in Germany, German cluster policy can serve as a model and starting point for cluster policy in Poland.

Table 2: Cluster policy in Germany and Poland

Source: based on Europe INNOVA Cluster Mapping Project, Germany, Poland, http://www.clusterobservatory.eu/ [access 10.03.2020]

Acknowledgment

The project is financed by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education in Poland under the programme” Regional Initiative of Excellence” 2019 – 2022 project number 015/RID/2018/19 total funding amount 10 721 040,00 PLN.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

References

- Boekholt, P., and Thuriaux, B., (1999), Boosting innovation: the cluster approach. Paris: OECD Publications [Online] Available at: http://www.msmetfc.in/images/05_03_2014_Boosting_Inovations_Cluster_Approach.pdf [Accessed 10 November 2018].

- Cluster policy in Europe, A brief summary of cluster policies in 31 European countries, (2008), Europe Innova Cluster Mapping Project, Oxford Research AS, January.

- Clusterplattform Deutschland at a glance, https://www.clusterplattform.de/CLUSTER/Navigation/EN/FederalLevel/federal-level.html

- Dzierżanowski M. (ed.), (2012) Directions and assumptions of Polish cluster policy until 2020 Recommendations of the Working Group for Cluster Policy, Warsaw

- Enright M. J., (2000) Survey on The Characterization of Regional Clusters: Initial Results, Institute of Economic Policy and Business Strategy: Competitiveness Program, Working Paper, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

- Europe INNOVA Cluster Mapping Project, Germany, Poland, http://www.clusterobservatory.eu/ [access 10.03.2020]

- Jankowiak A.H., (2019) Cluster Policy Based on Key National Clusters –A Case Of Poland, Proceedings part I of the international scientific conference Hradec Economic Days, Vol. 9(1).

- Ketels Ch., (2016), in: M. D. Nielsen, Supporting Clusters Interregional Collaboration-Status And Moving Ahead, www.clusterexcellencedenmark.dk [access 15.12.2019]

- Ketels Ch.H.M., (2003), The Development of the cluster concept – present experiences and further developments, NRW conference on clusters, Duisburg

- Lindqvist, G., Ketels, Ch. and Sölvell, Ö., (2013), The Cluster Initiative Greenbook 2.0., Ivory Tower Publishers, Stockholm.

- Meier zu Köcker G. and Garnatz L., (2012), Klastry jako instrumenty inicjujące prace badawczo-rozwojowe między Niemcami a Koreą, Polska Agencja Rozwoju Przedsiębiorczości, Warszawa.

- Porter M. E., (2001), Porter o konkurencji, PWE, Warszawa.

- Preissl, B., (2003), Innovation Clusters : Combining Physical and Virtual Links, DIW Discussion Papers, No. 359.

- Responsible Development Plan, https://www.gov.pl/web/fundusze-regiony/plan-na-rzecz-odpowiedzialnego-rozwoju [access 7.03.2020]

- Strategia Rozwoju Kraju do 2020, (2012) Warszawa, http://ww.mrr.gov.pl, last access 2018/09/25

- The Concept of Clusters and Cluster Policies and their Role for Competitiveness and Innovation: Main Statistical Results and Lessons Learned.

- The European Secretariat for Cluster Analysis (ESCA), available at https://www.cluster-analysis.org/ [date of entry 20.03.2020]

- The German programme “Go-Cluster” – Successful clusters through excellent management, https://www.clustercollaboration.eu/cluster-networks/german-programme-go-cluster-successful-clusters-through

- Uyarra E., (2014), Cluster Policy in an Evolutionary World? Rationales, Instruments and Policy Learning, presentation for Cluster Policies from a Cluster Life Cycle Perspective, International Dissemination Workshop, 23-24 June, Berlin.

- What are Clusters, UNIDO, http://www.clustersfordevelopment.org/seite.mv?10-10-00-00+&uid=5963F822000AB3D3000001C000000000.