Introduction

Youth is one key element in a nation. Understanding youth and all things related to youth is important since youth will become leaders of a nation in the future. Entrepreneurship is one activity that attracts young people. Specifically, studies show that the main attraction for young people to become entrepreneurs is self-employment that has the potential to create jobs, significant financial rewards, prestige, and others. Many studies have been conducted in predicting and understanding the intentions of youth to become an entrepreneur (e.g. Ozaralli & Rivenburg 2016; Dogan, 2015; Hattab, 2014; Kuttim et al., 2014; Peng et al., 2012; Campo, 2011; Turker & Selcuk, 2008; Van Gelderen et al., 2008). On the other hand, young people have characteristics that may hamper them in becoming sustainable entrepreneurs who do not easily give up in their entrepreneurship. Temptation to work with established companies and having consistent and stable income are two main factors that may influence their intention to quit as entrepreneurs.

Intention to leave or quit is a condition when a person does not feel comfortable and does not enjoy their jobs or works. Intention to quit may happen to entrepreneurs when those entrepreneurs have difficulties and problems with their business. Especially for young entrepreneurs, intention to quit as an entrepreneur is one solution that they can easily consider when they encounter problems. Many researches have been conducted in understanding the intention to leave in the context of organization and companies (e.g. De Hoer, Giacomin, & Janssen, 2016; Rizwan, 2014; Masum et al., 2010; Saungweme & Gwandure, 2011). Furthermore, research in entrepreneurship also shows that the intention to leave is one important topic (e.g. Forster-Holt, 2013; Zhu, Burmeister-Lamp, & Hsu, DeTienne, 2010; Justo & DeTienne, 2008), however, it is rarely studied (DeTienne, 2010). Moreover, as far as the researcher knowledge reached, there is no research conducted in predicting young entrepreneur’s intention to quit, especially in the context of Indonesia.

Young and tough entrepreneurs are especially needed for Indonesia as a developing country. The resilience of young entrepreneurs is expected to be able to survive in creating jobs and will have an impact on the improvement of the nation’s economy. Predicting the intention to quit for young entrepreneurs in empirical studies is one way to understand the toughness of young entrepreneurs whose some of their common traits are being more unstable and sometimes easier to give up. Therefore, this paper aims to examine the relationship between personal values and intention to quit, with the entrepreneur who has an attitude toward entrepreneurship as a mediating variable. Personal values will be measured by applying terminal and instrumental values as proposed by Rokeach (1973). Terminal values refer to beliefs in achieving ultimate goals and instrumental values represent ways in achieving end goals. Those instrumental and terminal values represent two separate, yet functionally connected systems (Rokeach, 1973). Thus, both types of these values affect people behavior in their daily life. However, few researches have been conducted to understand instrumental and terminal values of entrepreneurs (e.g. Jakubczak, 2016; Uy, 2011). Furthermore, as far as the researcher knowledge reached, there is no study that focuses on applying these two types of personal values in predicting youth intention to quit as an entrepreneur in Indonesian context. Based on the explanation before, the research questions of this paper can be stated as follows:

RQ1 : Is there a positive relationship between terminal values and attitude toward entrepreneurship?

RQ2 : Is there a positive relationship between instrumental values and attitude toward entrepreneurship?

RQ3 : Is there a negative relationship between attitude toward entrepreneurship and intention to quit as entrepreneur?

Literature Review

Entrepreneurial Intention

Intention is a motivation to engage the behavior in the future (Blackwell, Miniard, & Engel, 2006). This motivation is the main antecedent variable in explaining people behavior. Several main attitude theories such as theory of reasoned action, planned behavior theory, and the theory of trying to put intention as the main antecedent variable that influences behavior. Related with entrepreneurship, entrepreneurial intention is defined as the intention to start a new business (Van Gelderen et al., 2008; Pilis & Reardon, 2007).

Entrepreneurial intention is one dependent variable that has received great attention by many scholars. Youth entreprenurial intention is important since youth are a potential driver of economic development of a nation. Moreover, many researchers also focus in understanding youth entrepreneurial intention (e.g. Ozaralli & Rivenburg 2016; Dogan, 2015; Kuttim et al., 2014; Peng et al., 2012; Turker & Selcuk, 2008; Pilis & Reardon, 2007). Youth entreprenurial intention is important since youth are a potential driver of economic development of a nation.

One phenomenon in working environment is the quit intention of the employee. Intention to quit is defined as individual’s decision to stop working in a company or organization (Aziz & Ramli, 2010). Intention to quit can be applied in entrepreneurship area. Specifically, start-up entrepreneurs or businessmen with long experience, or young or old entrepreneur may face the possibility of quitting from entrepreneurship. There are several factors for entrepreneurial exit such as; family matters (e.g. DeTienne & Wennberg, 2014), personal characteristics (e.g. Justo & DeTienne, 2008; Stam, Thurik, & van der Zwan, 2008), institutional environment (e.g. Stam et al., 2008), and others.

People’s intention can be influenced by many factors. Attitude theories such as; the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1988) and the theory of trying (Bagozzi) show that two main antecedent variables of people’s intention are attitude and subjective norms. This research applied the value-attitude-behavior hierarchy that was developed by Homer and Kahle (1988). In other words, this hierarchy shows that personal values influence people’s behavior indirectly through attitude.

Attitude

An attitude is defined as a learned predisposition to behave in a consistently favorable or unfavorable way toward a given object (Schiffman & Wisenblit, 2015, p.172). Attitude is considered as one main variable in explaining people variable in which attitude can be divided into three dimensions: cognitive (i.e., belief), affective (i.e., feel), and conative (i.e., intention).

Attitudes can be explained into two main types in people behavior perspectives (Blackwell et al., 2006). The first type is attitude toward the object (Ao). Ao represents a consumers’ evaluation toward objects such as products, brands, or services. The second type is attitude toward the behavior (Ab). It represents an evaluation of performing a particular behavior such as buying or doing something. As Ab focuses on performing behavior, then it can be stated that Ab is strongly related to behavioral intention (Blackwell et al., 2006). Thus, this research applied the concept of Ab in predicting people’s intention.

Values

Personal values are one significant variable in explaining people’s attitude and behavior. Value refers to a desirable trans-situational goal which varies in importance, and it serves as a guiding principle for people in life (Schwartz, 1992). Specifically, values influence many aspects in human lives and they represent what are important to our lives (Bardi & Schwartz, 2003).

Entrepreneurship research show that one important variable that influences entrepreneurs’ behavior is their personal values (e.g. Malovics et al., 2015; Rohani, Kamariddun, Yahya, & Sanidas., 2015; Nguyen & Nguyen, 2008; Halis, Ozsabunouglu, & Ozsagir 2007; Hemingway 2005; Lindsay, Jordaan, & Lindsay, 2005). However, those studies applied personal values in general. Rokeach (1973), on the other hand, suggested that personal values can be divided into 2 types: instrumental values and terminal values. Terminal values refer to a condition that has ideal or desired end goals. On the other hand, instrumental value is an ideal way of behaving in order to achieve terminal values. Those instrumental and terminal values represent two separate, yet functionally connected systems (Rokeach, 1973). Thus, both types of values affect people’s behavior in their daily life.

This research developed a model that pictures the relationship between personal values (that is, instrumental and terminal values) and attitude toward becoming an entrepreneur. It is predicted that there will be a positive relationship between these two types of values toward attitude and the potential of becoming an entrepreneur. Attitude theories show that the stronger the attitude of a person, the stronger the intention to perform a behavior. Since this research focuses on the intention to quit as an entrepreneur, this negative relationship between attitude and intention to quit is predicted.

Research Model and Hypotheses

Source: developed for this research (2017)

Hypotheses:

H1: Instrumental values will be positively related to attitude toward becoming an entrepreneur.

H2: Terminal values will be positively related to attitude toward becoming an entrepreneur.

H3: Attitude toward becoming an entrepreneur will be negatively related to intention to quit as an entrepreneur.

Research Method

Sample and Sampling Design

The target population covered in this research was undergraduate students who are small and medium business entrepreneurs and who live in Jakarta and Tangerang. The sample size of 150 was set for this research. This research applied purposive sampling. In particular, only students who have their own business within the past year period can be a respondent of this study.

Survey

Data were collected a self-administrated questionnaire and was collected in one month period. The questionnaires were delivered to respondents by the researcher and research assistants. This method was chosen because this method gives flexible time for respondents to answer the questionnaire. To appreciate respondents’ time, a pen was given to respondents in order to appreciate their participation in this research.

Measures and the Goodness of Measures

This study applied multi-item scales that were adapted from previous studies to measure constructs in this research model. Five-point Likert scale was used to measure all items in the questionnaire. All constructs’ indicators were adapted from Sihombing et al (2016), Ariff et al. (2010), and Linan and Chen (2000). The goodness of measures was tested through reliability and validity analysis.(Sekaran & Bougie, 2016). Sekaran and Bougie (2016) pointed out that reliability analysis is making sure that the instrument is consistently measuring the concept that is measured. This analysis applies the examinations of Cronbach‘s Coefficient Alpha and item-to-total correlations (Churchill, 1979). After having done with reliability checking, validity analysis is conducted to assess how well the instrument measures the particular concept (Sekaran & Bougie, 2016). Construct validity is applied in this research through the assessment of convergent and discriminant validity. Discriminant validity of the applied constructs was tested by assessing correlations between constructs (Bagozzi et al., 1991). Specifically, discriminant validity was achieved when the factor correlations were significantly different from one another.

Analysis Data

After the research data was examined to confirm that the data are realible and valid, a structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to test the relationship between constructs. SEM predicts the relationships among the latent variables and encompasses two components: a measurement model and a structural model (Schreiber et al., 2006).

Results and Discussion

Respondents’ Profile

A total of 120 questionnaires were returned out of 150 distributed. Eight questionnaires were eliminated due to being incomplete. Hence, 112 valid/correct questionnaires were obtained, yielding a response rate of 74.6%. The profile of the sample reveals that males constituted about 55 per cent of the sample. Those between 18-20 years old represent 70.5% of the sample, and most of them (78.6%) have experience as entrepreneurs for about a year.

Descriptive Statistics, Reliability, and Validity

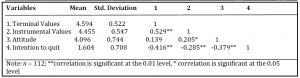

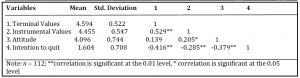

The means, standard deviations, and correlations for terminal values, instrumental values, attitude, and intention to quit are shown in Table 1. The table also shows that a positive relationship at 0.01 has been found among personal values, attitude, and intention. However, no significant relationship has been found between religious values and attitude, and religious values and intention

Table 1: Descriptive statistics and correlations

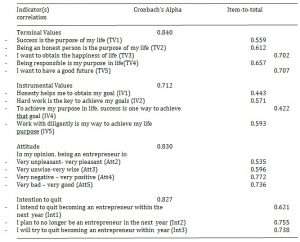

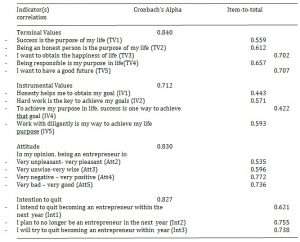

Before testing the hypotheses, the goodness of measures was established through reliability and validity analysis (Sekaran & Bougie, 2016). Sekaran and Bougie (2016) pointed out that reliability analysis is making sure that the instrument is consistently measuring the concept that is measured. This analysis applied the examinations of Cronbach‘s Coefficient Alpha and item-to-total correlations (Churchill, 1979) as shown in Table 2. Two items of the research questionnaire (one from instrumental values and one from attitude) were excluded because the item-to-total correlation was below 0.4.

Table 2: Cronbach Alpha and item-to-total correlation

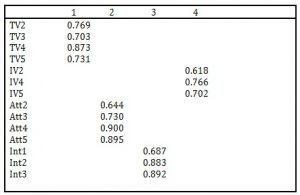

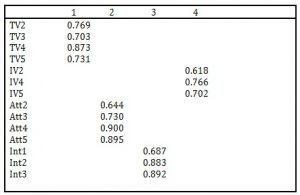

Validity analysis refers to how well the instrument measures the particular concept (Sekaran & Bougie, 2016). Construct validity is applied in this research through the assessment of convergent and discriminant validity. Discriminant validity of the applied constructs was tested by assessing correlations between constructs (Bagozzi & Yi, 1991). Specifically, discriminant validity was achieved when the factor correlations were significantly different from one another. Table 1 above shows that acoefficient correlation among constructs is different from the one which indicated that discriminant validity was achieved. On the other hand, Hill and Hughes (2007) stated that convergent validity was assessed by applying exploratory factor analysis (Table 3). Table 3 shows that the factor loadings are statistically significant indicating that convergent validity was achieved.

Table 3: Exploratory Factor Analysis

Structural Equation Modeling

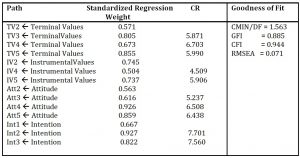

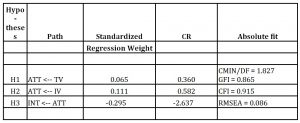

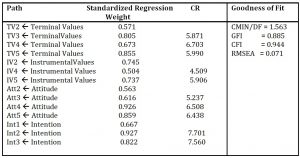

Structural equation modelling was applied to validate the proposed model (Figure 1). The structural equation analysis was conducted in two main steps: the estimation of the measuring model (Confirmatory Factor Analysis, CFA) and the estimation of the structural model. The measurement model focuses on the link between factors and their measured variables. Furthermore, the relationship between the constructs was assessed in the structural model.

CFA using maximum likelihood method was performed to assess the measurement model (Table 4). The results show a marginal-fit model (GFI = 0.784, CFI = 0.867, RMR = 0.055, CMIN/DF= 1.781). Table 5 shows the parameter estimated for structural paths. The results indicated that estimates for a set of recommended indices (GFI = 0.780, CFI = 0.864, RMR = 0.060, CMIN/DF= 1.794) were in the range of accepted threshold. It can be stated that the proposed model has an acceptable fit.

Table 4: Confirmatory Factor Analysis

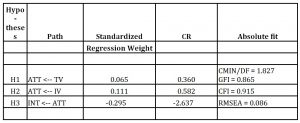

Table 5 shows that all path estimates were found not to be statistically significant except the path between attitude toward becoming an entrepreneur and intention to quit (H3). Those two hypotheses that are not significant are the relationship between terminal values and attitude toward becoming an entrepreneur (H1) and the relationship between instrumental values and attitude toward becoming an entrepreneur (H2).

Table 5: Parameter Estimates for Structural Paths

Note

TV : Terminal values

IV : Instrumental values

INT : Intention to quit

ATT : Attitude toward becoming an entrepreneur

Discussion

Personal values are our beliefs or principles that will direct us in understanding what is meaningful and important to us. Rokeach (1973) divided personal values into two types of values: terminal and instrumental values. Terminal values refer to beliefs that are ultimate things to achieve such as happiness and success in life. On the other hand, instrumental values are beliefs as modes of conduct to achieve ultimate things in life such as hard-working and honesty. In this research, the two types of personal values are having no significant relationship with attitude toward becoming an entrepreneur.

The insignificant relationship between personal values (terminal and instrumental values) with attitude toward becoming an entrepreneur can be explained as follows; this research applied student samples in understanding their intention to quit as an entrepreneur. Several researches show that many young people have embraced personal values such as individualism (Jang, 2015; Sihombing, 2014; Sun & Wang, 2010), materialism (Jang, 2015), freedom, and others. These values such as individualism and materialism are across many countries as influenced by western culture and spread through globalization and technology. In other words, it can be stated that the personal value of the young today is not focused on their ultimate goals in life such as happiness, success, responsible people, honest people, and a good future. Yet, young people focus on their own personal values such as individualism and materialism as stated earlier. This research confirms the negative relationship between attitude toward becoming an entrepreneurs and the intention to quit as an entrepreneur. This result of the relationship between attitude and intention is consistent with previous findings (Rahab & Wahyuni 2013; Ibragimova et al. 2012; Kuang et al. 2012; Cai & Shannon 2011; Teh & Yong 2011; Teh et al. 2011; Zhang 2011; Bock et al. 2010; Chen et al. 2009; Lin 2007; Wu and Li 2007; Lin & Lee 2004). Thus, it can be stated from the research results that respondents in this research (i.e., youth entrepreneurs) have positive attitude toward becoming an entrepreneur (mean = 4.096) and they have no intention to quit as an entrepreneur (mean = 1.604). The result can be interpreted that the more positive attitude they have toward becoming an entrepreneur, the less their intention to quit as an entrepreneur. This result was delighting since it gives hope that youth entrepreneur can be tough and can sustain their job as entrepreneur.

Conclusion

This research is motivated by the need to understand the relationship between personal values and attitude toward becoming an entrepreneur, and the relationship between attitude toward becoming an entrepreneur and intention to quit as an entrepreneur. Entrepreneurs’ supports, especially young entrepreneurs, will no doubt have a positive impact on the nation’s economy. However, young entrepreneurs need to continue to be given attention, nurtured, and supported by the government and the society so that they become a formidable businessman who can create jobs for many people and can have a positive impact on the environment, society, and nation.

We believe that our study adds to the understanding of the determinants of intention to quit among youth entrepreneurs. Specifically, this research found that personal values (i.e., terminal and instrumental values) have no significant relationship with young entrepreneurs’ attitude but their positive attitude toward being entrepreneur has a negative significant relationship with their intention to quit as entrepreneurs. Understanding entrepreneurship, especially the knowledge of the factors that explain entrepreneurial intention to quit are indispensable for practical and theory matter.

Limitations and Recommendation for Further Research

The main objectives of this study are to predict the relationship between personal values (i.e. terminal and instrumental values) and attitude toward becoming an entrepreneur, and the relationship between attitude toward becoming an entrepreneur and intention to quit as an entrepreneur. There are two main limitations of this study. First, this research applied students who are young entrepreneurs as research respondents. Specifically, this research tests the fit of the model within a single university in Indonesia. Thus, the results of this study were limited to this sample. Furthermore, generalization cannot be made to Indonesian youth. In relation with this, further research should attempt to replicate this research to a wide array of settings and populations.

Second, this research applied cross-sectional survey data to test the hypotheses. On the other hand, cross-sectional survey data reflects that respondents are recorded only one time. Therefore, the results only infer the temporal relationship between variables and not the causality among variables. Thus, it is recommended that future studies utilize a longitudinal study.

References

- Ariff, A.H.M., Bidin, Z., Sharif, Z. and Ahmad, A. (2010), ‘Predicting Entrepreneurship Intention Among Malay University Accounting Students In Malaysia,’ UNIFAR e-journal, 6, 1. Available: http://ejournal.unirazak.edu.my/articles/Predicting_Entrepreneur_p16n1Jan10.pdf

- Aziz, N.N.A. and Ramli, H. (2010), ‘Determining Critical Success Factors Of Intention To Quit Among Lecturers: An Empirical Study At Uitm Jengka,’ Gading Business and Management Journal, 14, 33-46.

- Bagozzi, R., Yi, Y., and Phillips, L. (1991). Assessing Construct Validity in Organizational Research. Administrative Science Quarterly, 36(3), 421-458.

- Blackwell, R.D., Miniard, P.W. and Engel, J.F. (2006). Consumer Behavior. 10th ed. USA: Thomson South-Western.

- Bock, G., Lee, J.Y. and Lee, J. (2010), ‘Cross Cultural Study on Behavioral Intention Formation In Knowledge Sharing,’ Asia Pacific Journal of Information Systems, 20(3), 1-32.

- Burgess,S.M. and Steenkamp,J.E.M. (1998). Value Priorities And Consumer Behavior In A Transitional Economy: The Case Of South-Africa. Working paper No. 166,The William Davidson Institute, University of Michigan Business School, USA.

- Cai, Y. and Shannon, R. (2012), ‘Personal Values And Mall Shopping Behavior: The Mediating Role Of Intention Among Chinese Consumers,’ International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 40(4), 290-318.

- Churchill, G.A. (1979), ‘A Paradigm For Developing Better Measures Of Marketing Constructs. Journal of Marketing Research,’ 16, 64-73.

- Chen, I.Y.L., Chen, N. and Kinshuk (2009), ‘Examining The Factors Influencing Participants’ Knowledge Sharing Behavior In Virtual Learning Communities,’ Educational Technology Society, 12(1), 134-148.

- Campo, J.L.M. (2011), ‘Analysis Of The Influence Of Self-Efficacy On Entrepreneurial Intentions,’ Prospect, 9(2), 14-21.

- De Hoe, R., Giacomin,O. and Janssen, F. (2016), ‘Entrepreneurial Exit And Explanatory Determinants Of Reentry Intention. Entrepreneurship, Culture, Finance And Economic Development,’ June 23-24, University of Lyon, France. Available at coachs.org/wp-content/upload/2015/09/session-24-Roxane-De-Hoe-et-al.pdf

- Dogan, E. (2015), ‘The Effect Of Entrepreneurship Education On Entrepreneurial Intentions Of University Students In Turkey,’ Ekonometri ve Istatistik Sayr, 23, 79-93.

- Fishbein, M. and Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, Attitude, Intention And Behaviour: An Introduction To Theory And Research. Reading: Addison Wesley.

- Forster-Holt, N. (2013), ‘Entrepreneur as “End”repreneur: The Intention to Retire,’ Small Business Institute Journal, 9(2), 29-42.

- Hattab, H.W. (2014), ‘Impact Of Entrepreneurship Education On Entrepreneurial Intentions Of University Students In Egypt,’ The Journal of Entrepreneurship, 23(1), 1-18.

- Hill, C. R. and Hughes, J. N. (2007), ‘ An Examination Of The Convergent And Discriminant Validity Of The Strengths And Difficulties Questionnaire. School Psychology Quarterly : The Official Journal of the Division of School Psychology,’ American Psychological Association, 22(3), 380–406. http://doi.org/10.1037/1045-3830.22.3.380

- Ibragimova, B., Ryan, S.D., Windsor, J.C. and Prybutok, V.R. (2012), ‘Understanding The Antecedents Of Knowledge Sharing: An Organizational Justice Perspective,’ Informing Science: the InternationalJournal of an Emerging Transdiscipline, 15, 183-205.

- Jang, H.S. (2015). Social Identities Of Young Indigenous People In Contemporary Australia, Neo-Colonial North, Yarabah. Springer: Switzerland.

- Jakubczak, J. (2016), ‘Young People Terminal And Instrumental Values Impact On Youth Entrepreneurship. Management Knowledge and Learning Joint International Conference,’ 25-27 May, Romania. Available: http://www.toknowpress.net/ISBN/978-961-6914-16-1/papers/ML16-176.pdf

- Justo, R. and DeTienne, D.R. (2008), ‘Family Situation And The Exit Event: An Extension Of Threshold Theory,’ Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research, 28(14), 1-13.

- Kahle, L.R., Beatty, S.E. and Homer, P. (1986), ‘Alternative Measurement Approaches To Consumer Values: The List Of Values (LOV) And Values And Life Style (VALS),’ Journal of Consumer Research, 13, 405-409.

- Klamer, A. (2003), ‘A Pragmatic View On Values In Economics,’ Journal of Economic Methodology, 10(2), 1-24.

- Kim, H.Y. and Chung, J. (2011), ‘Consumer Purchase Intention for Organic Personal Care Products,’ Journal of Consumer Marketing, 28(1), 40-47.

- Kuang, L.C., Davidson, E. and Yao, L. (2012). A Planned Behavior-Based Investigation of Knowledge Sharing In Construction Industry. Proceedings of International Management & Engineering Conference (EMC 2012). Available: umpire.ump.edu.my/3187/1/Lee_EMC_2012.paper.pdf

- Kuttim, M., Kallaste, M., Venesaar,U. and Kiis, A. (2014), ‘Entrepreneurshipeducation at University Level And Students’ Entrepreneurial Intentions,’ Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 110, 658-668.

- Lin, H. (2007), “Effects of Extrinsic and Intrinsic Motivation on Employee Knowledge Sharing Intentions,’ Journal of Information Science, 33(2), 135-149.

- Lin, H. and Lee, G. (2004), ‘Perceptions of Senior Managers Toward Knowledge-Sharing Behavior,’ Management Decision, 42(1), 108-125.

- Linan, F. and Chen, Y. (2006), ‘Testing The Entrepreneurial Intention Model On A Two-Country Sample,’ Document de Trball num.06/7. Department d’Economia de l’Empresa. Available: http://selene.uab.es/dep-economi-empresa/.

- Masum, A.K.M., Azad, M.A.K., Haque, K.E., Ben, L., Wanke, P. and Arslan, O. (2010), ‘Job Satisfaction and Intention to Quit: an Empirical Analysis of Nurses in Turkey.” PeerJ, 4, e1896, http://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.1896.

- Ozaralli, N. and Rivenburgh, N.K. (2016), ‘Entrepreneurial Intention: Antecedents To Entrepreneurial Behavior In The USA and Turkey,’ Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 6(5). Available: journal-jjger.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40497-016-0047-x.

- Peng, Z., Lu, G., and Kang, H. (2012), ‘Entrepreneurial Intentions And Its Influencing Factors: A Survey Of The University Students In Xi An China,’ Creative Education, 3, 95-100.

- Pilis, E. and Reardon, K.K. (2007), ‘The Influence of Personality Traits and Persuasive Messages on Entrepreneurial Intention: A Cross-Cultural Comparison,’ Career Development International, 2(4), 382-396.

- Rahab and Wahyuni, P. (2013), ‘Predicting Knowledge Sharing Intention Based On Theory Of Reasoned Action Framework: An Empirical Study on Higher Education Institution,‘ American International Journal of Contemporary Research, 3(1), 138-147.

- Rizwan, M. (2014), ‘Determinants of Employees Intention To Leave: A Study From Pakistan,’ International Journal of Human Resources Studies, 4(3), 1-18.

- Saungweme, R. and Gwandure, C. (2011), ‘Organisational Climate Andintent to Leave Among Recruitment Consultants Injohannesburg, South Africa,’ Hum.Ecol, 34(3), 145-153.

- Schiffman, L.G. and Wisenblit, J.L. (2015). Consumer Behavior, 11th USA:Pearson.

- Schreiber, J.B., Stage, F.K., King, J., Nora, A. and Barlow, E.A. (2006), ‘Reporting Structural Equation Modeling and Confirmatory Factor Analysis Results: A Review,’ The Journal of Educational Research, 99(6), 323-337.

- Sekaran, U. and Bougie, R. (2016). Research Methods for Business, 7th UK: Wiley.

- Sihombing, S. O., Pramono, R., Zulganef and Ismanto, I. (2016), ‘Instrumental and Terminal Values of Indonesian Micro-Finance Entrepreneurs: A Preliminary Report,’ International Journal of Economic Research, 13(3), 841-853.

- Sihombing, S.O. (2014), ‘Identifying Current Values of Indonesian Youth,’ Proceeding of the 9th International Conference on Business and Management Research, 24-25 October, Kyoto University, Kyoto.

- Sun, J. and Wang, X. (2010), “Value Differences between Generations in China: A Study in Shanghai,’ Journal of Youth Studies, 13(1),65-81.

- Teh, P., Yong, C., Chong, C. and Yew, S. (2011), ‘Do The Big Five Personality Factors Affect Knowledge Sharing Behavior? A Study Of Malaysian Universities,’ Malaysian Journal of Library & Information Science, 16(1), 47-62.

- Turker, D. and Selcuk, S.S. (2008), ‘Which Factors Affect Entrepreneurial Intention Of University Students,’ Journal of European Industrial Training, 23(2), 142-159.

- Van Gelderen, M., Brand, M., Van Praag, M., Bodewes, W., Poutsma, E. and Van Gils, A. (2008), ‘Explaining Entrepreneurial Intentions By Means of The Theory Of Planned Behavior,’ Career Development International, 13(6), 538-569.

- Wu, W. and Li, C. (2007), ‘A Contingency Approach To Incorporate Human, Emotional And Social Influence Into A TAM For KM Programs,’ Journal of Information Science, 33, 275-297.

- Zhang, P. (2011), ‘Analysis Of Factors Affecting Individual Knowledge Behavior In Construction Teams In Hong Kong,’ Thesis. The University Of Hong Kong.

- Zhu, F., Burmeister-Lamp,K. and Hsu, D.K. (2014), ‘To Leave Or Not To Leave/ The Role Of Psychological Ownership,Family Support and Hindrance-Related Stress In Entrepreneurs’ Venture Exit Decisions,’ Available: http://conference.iza.org/conference_files/EntreprR2014/burmeister-lamp_k5839.pdf