Introduction

Block Model of Teaching (BMT), also called Intensive Mode of Delivery (IMD) has been considered as a teaching approach that helps to increase the level of productivity by having a compressed format with more instructional methods (Serdyukov 2008). Although the IMD has shorter in-class hours compared to traditional teaching courses, the class is held more frequently and in longer sessions. According to Wlodkowski & Ginsberg (2010), these classes often take place in blocks of two to eight hours per class. According to Davies (2006), this model has large amount of teaching time, which can take whole-day sessions, last for several weeks and may include weekends.

Despite the fact that BMT is not a new concept to secondary or high schools, the adoption of this mode of teaching in universities is still very limited. Besides, there is very limited information regarding how universities in the world adopt this mode of teaching. More importantly, there is a lack of research that investigates lessons that can be learnt from higher education institutions which have already adopted BMT.

As several aspects of BMT implementation have not been adequately addressed by previous researchers, it is necessary to conduct research that can shed light on more aspects of the BMT implementation. This includes how BMT has been implemented in various universities, responsibilities of implementors, level of engagement of teaching staff and students, how much time teachers and students should spend in class, the assessments regime for BMT subjects and whether BMT can help universities to enhance students’ performance or focus. Such aspects have not been addressed by previous researchers. Therefore, by conducting this research, the researchers aim to provide a clearer picture of the BMT implementation at universities, and most importantly, providing the lessons that can be learned from past implementations. Thus, the research question underlying this paper is “What insights can be learnt from the implementation of Block Model of Teaching in higher education?”

The potential findings of this paper will provide useful information to universities which are considering whether or not to implement BMT. Moreover, the BMT implementation project teams at interested universities can gain knowledge to enhance the success of the BMT implementation projects and learn from the mistakes that other universities have made. Besides, students, parents and educational providers can have more insights to make their own decision whether BMT should be a suitable mode for learning at tertiary level.

The rest of the paper is as follows. After this introductory section, literature review will be discussed. Next, research methodology will be presented. Finally data analysis and research outcomes will be demonstrated, followed by discussion of findings and concluding remarks.

Literature Review

As we are living in an age where our surrounding environment is changing very quickly, universities are urged to alter their teaching models to adapt to the rapid transformation. Block mode of teaching, which is a relatively new teaching model in the tertiary sector, is considered as an effective way in enhancing students’ performance. The model is believed to have greater impacts on younger students who have more active lifestyles, tend to work and study at the same time. These students are also more familiar with technologies than mature-age students, which makes this new teaching model feasible due to the importance of the use of technology in BMT model.

Although BMT is often known as an intensive mode of delivery or accelerated teaching method or time-shorten teaching method, there are various, and perhaps, slightly different definitions for these terms (Davies 2006). Despite various definitions of the terms BMT, IMD and accelerated teaching, Davies (2006) states that overtime these terms have been used interchangeably where users refer to the courses that have shorter duration but more frequent and maybe longer hour classes. For the purpose of this research, the authors rather not trying to distinguish these three terms but considering them all to be almost the same as per Davies’ findings.

Although BMT has been implemented and proven its efficiency in high school and lower level of schooling, it has very limited implementation at tertiary level (Ball et al., 1996). According to Davies (2006), universities are now urged to transform from preparing students for job markets to delivering courses for the convenience of students, especially the mature-age and life-long learners.

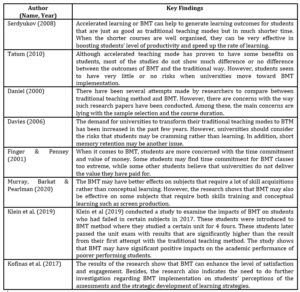

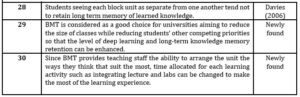

Table 1 shows the findings of previous studies regarding the BMT implementation in various universities.

Table 1: Overview of the relevant research studies

Research Methodology

Research Methodology

This study has chosen the interpretivism research paradigm. Interpretivism is a research paradigm that was developed from the studies done by some German philosophers like Edmund Husserl and Wilhelm Dilthey. Interpretivism suggests that research questions can be answered based on human experience and social reality. This study employs a qualitative research approach. Qualitative research approach is a qualitative investigation which employs textual data as instruments to make interpretation and uncovers hidden meaning (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016).

Secondary data analysis is used as research method for this research project. According to Johnston (2014), ‘Secondary data analysis’ is an empirical research method and systematic exercise with its own set of processes and evaluative tasks that utilizes data that have been gathered by other people for a different primary purpose. For this study, the steps proposed by O’Leary (2017) for Secondary Data Analysis have been followed: establishing a research question; finding data; assessing data relevance; evaluating data credibility; and data.

Data Collection

The study collected secondary data. Secondary data are the data that have been collected by someone else but can be used for re-analysis to address another research question (Smith & Smith Jr, 2008,). As this study focuses on learning lessons from BMT implementation in tertiary sector, the data were collected from secondary sources such as the website of universities which had adopted BMT, discussion forums, blogs, open letters, educational conferences, magazine articles, news and so on. Overall, around 100 pages of data were collected from 32 different sources. Examples of sources from which data were gathered include: the Educator Higher Education Edition, Inside Higher ED, Campus Morning Mail and university information websites such as Victoria University and University of Toronto.

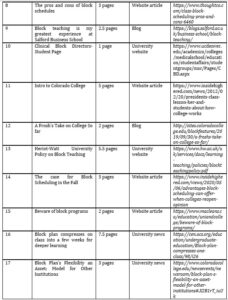

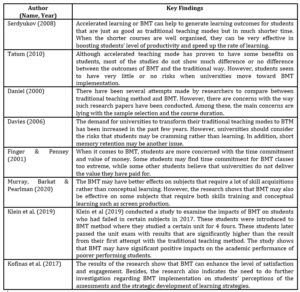

These data contain information regarding how BMT has been implemented in different universities around the world and the impacts it has on the performance of students and teaching staff. These data are available to the public and had been collected and filtered out irrelevant information. Table 2 provides examples of the data collected along with their sources.

Table 2: Examples of the data collected and their sources

Data Analysis

This study employed the thematic analysis method for analyzing the data. Thematic analysis is defined as a method for establishing and breaking-down the meaning contained within the data gathered, to enable researcher to reach answer to their research question (Braun and Clarke, 2006). In line with past research (e.g., Maguire and Delahunt (2017); Braun and Clarke (2006)), this research undertook the following steps for data analysis:

- Step 1: Reading and re-reading the collected data to make the self-familiarized with the data;

- Step 2: Establishing codes;

- Step 3: Examining the data along with codes produced to find themes or pattern of information; and

- Step 4: Assessing and outlining the themes and creating a table of themes.

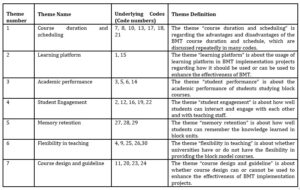

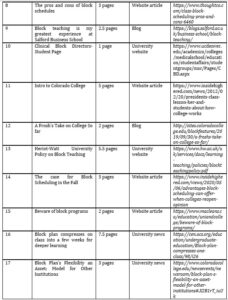

After codes are identified and generated, it is essential to identify themes. According to Vaismoradi et al. (2015), theme is defined as an implicit topic or pattern that reflects an idea which has been mentioned or discussed repeatedly. Although theme identification is one of the most fundamental tasks in qualitative research, it relies heavily on researchers’ intuition. Very often researchers need to revisit their dataset and identified codes so that they can identify patterns or themes. In this research, the dataset and identified codes have been revisited by the researcher very often. From there, the researcher started to classify, label, group and regroup each code until final consolidated themes are well defined. Table 3 shows the themes established in this research along with their definition and underlying codes.

Table 3: Table of Themes

Results

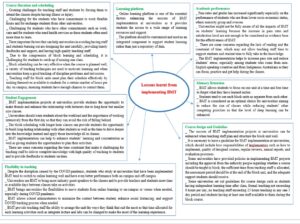

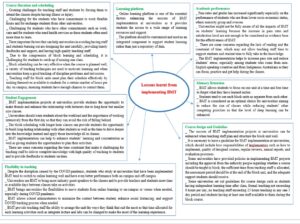

After analyzing codes and creating a table of themes, a big picture of the research findings was produced which is depicted in Figure 1. There were seven themes found from the data including course duration and scheduling, learning platform, academic performance, student engagement, memory retention, flexibility in teaching, and course design and guidelines. These themes are the patterns that are mentioned and discussed the most in the collected dataset. Moreover, 30 lessons were extracted from the data which can help higher education institutions in their BMT adoption initiatives. In what comes below, all the themes are explained along with examples of lessons found under each theme.

Figure 1: Taxonomy of Lessons Learnt from BMT Implementation

Student course workload, scheduling, and time management

Course workload, scheduling or time management are two of the most significant elements that make BMT outstanding from the other teaching methods at universities. Course duration itself is a theme that helps to explain the challenges and advantages BMT implementation can bring when being implemented at universities. Example of lessons learnt under this theme include the pressure to carrying the classes despite illness or injuries, the pressure on students who have other commitments such as work or health care, and the pressure on catching up when missing a class.

Learning platform

Learning platform is one of the most important factors that universities must consider when implementing BMT. Although almost all universities around the world have online learning platforms in place to facilitate student learning, the platform is extremely important in universities implementing BMT as without an effective one, students will find it challenging to keep up with the intensive learning classes. Several collected data have mentioned the usage of learning platform regarding how it can support students’ learning and how it should be customized to suit the teaching method. Example of lessons learnt under this theme include, “online learning platform is one of the essential factors enhancing the success of BMT implementation at universities as it provides students the access to a wide range of learning resources and support”.

Academic performance

BMT implementation projects tend to raise concerns regarding how well students perform. Very often, the teaching method is compared to the traditional teaching method. Academic performance is one of the themes that have been discussed the most when it comes to BMT implementation projects. Example of lessons learnt under this theme include, “Following the implementation of BMT at universities, the pass rates and grades has increased significantly especially on the performance of students who are from lower socio-economic status, ethnic minority group and oversea”.

Student Engagement

Student engagement is another theme that was often discussed in our data set. As in block units, students tend to have longer hour classes and spend more time with teachers for one unit; the level of engagement is one of the aspects that have been discussed and compared to the traditional learning method the most. Therefore, universities when considering BTM implementation often spend a great amount of time to consider if the projects can help to increase the level of student engagement, and therefore, enhancing their learning processes. Example of lessons learnt under this theme include, “BMT implementation projects at universities provide students with the opportunity to make friends and enhance the relationship with lecturers due to long-hour but smaller size classes”.

Knowledge memory retention

Memory retention is one of the main themes that were highlighted in many places. The theme is about the impacts of BMT implementation on students’ ability in concentrating and memorizing the lessons and knowledge in the long term. A wide range of collected data has provided this theme. Example of lessons learnt under this theme include, “BMT allows students to focus on one unit at a time and less time to forget what they have learned earlier in the course so that their performance in final exams can be enhanced”.

Flexibility in teaching

Flexibility in teaching is often discussed as an advantage of the BMT implementation projects at universities. This theme is about how much flexibility universities can have when implementing BMT. Such flexibilities can be the ability to switch between online and on campus learning, the ability to bring more guests, the authority to allocate timing for each study activities and the ability to maintain social distancing and COVID tracking during the COVID pandemic time. Example of lessons learnt under this theme include, “Despite the disruption caused by the COVID pandemic, students who study at universities that have been implemented BMT tend to switch to online learning well and maintain good performance both on campus and off-campus”.

Course design and Guideline

Course design and guideline is an aspect that has been discussed in data collected from many universities that have been implementing this teaching model. These guidelines help to set some foundations regarding whether a unit should be taught in block, how teaching staff can plan the block unit, how much time students should spend in class and how much time teachers should be teaching. Example of lessons learnt under this theme include, “The success of BMT implementation projects at universities can be enhanced when teaching staff plan and structure the block unit well enough to ensure student learning development progress”.

Research Contributions

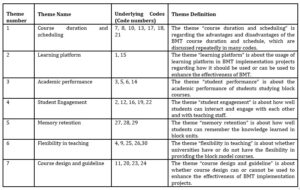

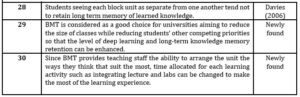

The results of the findings confirm some findings from the literature papers conducted by other researchers, which are discussed in the section Literature Review. For example, the findings confirm the findings from Kofinas et al. (2017); Bourgeois, Drayton and Brown (2011) and Yao and Collins (2018) regarding the high level of engagement students can have access to when taking block units. As another example, the increase in pass rate and academic performance is also confirmed in accordance with Klein et al (2019). Table 4 demonstrates the contribution of this research, and provides where the findings are new to the literature and when the findings confirm existing literature.

Table 4: Research contributions

Discussing Implications of Findings for Practitioners

The findings of this research which dealt with lessons learnt from the implementation of BMT projects at universities can benefit different groups of people including the educational providers, students who are about to enter colleges, parents whose children are about to start college, government, researchers, educational practitioners or educational researchers, and organizations who are sending their employees for higher training and learning.

Educational providers are the group that can benefit from this study the most. As the research can provide information regarding the lessons to be learned from the implementation of BMT projects at universities, educational providers can obtain this insight and use it to compare with their current practices. The information such as the advantages, disadvantages, implementation lessons and the guidelines can be used for educational providers to apply to their practices. These educational providers can be universities or colleges that are interested in implementing this teaching model or the universities that already implemented it and need to review their practices.

Given the COVID pandemic, many universities may also be interested in the BMT as it can allow the schools to operate safely and allow the flexibilities to move students online or on campus. These universities can learn from the advantages of BMT in dealing with the COVID situation provided in this paper. According to the lesson learned in code 4, 25 and 26, BMT implementation projects have proven their effectiveness in giving universities the flexibility to move students to online learning and bring them back to campus when it is safe. These lessons also show that students who have been taking block classes tend to adapt better when classes are moved to online.

Universities that decide to implement BMT can use the insights provided in this paper regarding the factors that help enhance the success of BMT implementation at universities such as setting up guidelines, planning the block unit well and having high quality staff. These are the lessons extracted from codes 11, 18, 19, 20, 21 and 24. As many universities that are well-known for their success in implementing BMT have been applying such lessons, the taxonomy provided herein is of highly valuable source information for universities that are interested in this teaching model. Besides, they should also pay attention to the aspects that may impact BMT implementation negatively such as students and staff being burnt out, students not seeing the block units as being connected, and the online learning platform not used effectively. These lessons are extracted from lessons C1, C13, C15 and C28.

Another group that can benefit from this research are students who are about to enter higher education. As there are a number of universities around the world that have successfully implemented BMT projects, students may find it hard to choose between universities with different teaching methods. As studying in tertiary education is usually time consuming and costly, the decision must be made wisely. By obtaining the information from this research, students can have a sense of how intensively the block units can be and how to avoid falling behind the block units. Students can also be aware of the advantages and the potential risks they may face when taking the block units (e.g. Lesson learnt in code 12). Students should also reconsider this teaching model if they have other commitments such as caring, works or requirements to have access to health services (referring to the lesson learnt in codes 8 and 10).

Another group that can benefit from this research are governments. As education has been one of many countries’ key industries in contributing to the economy, many governments have been striving to enhance the quality of their tertiary education systems. With many universities becoming interested in the BMT, governments need to consider if the model is suitable for their educational environment and whether a set of guidelines should be applied to all universities when implementing BMT projects. This research paper provides the governments with some information regarding the need to have guidelines in place. The lessons C20, C23 and C24 herein show that the guidelines can only be effective when they can provide clear criteria for approving block unit, define clear responsibility, provide the maximum number of in-class hours and how to assess the BMT implementation projects.

Organizations aiming to send their employees for higher training can also find this research useful as it can help them consider whether block courses are suitable for their employees. As mentioned in lessons C8, C10 and C29, the block course can be intense, and students do not have much time for other activities during the block. Therefore, if organizations are expecting their employees to work and study at the same time, they may need to reconsider other teaching and learning approaches for their employees.

Conclusions

This paper aimed at providing a clearer picture of the BMT implementation at universities by extracting several important lessons that can be learned from past implementations of BMT in higher education sector. By conducting qualitative research, this study provided a taxonomy containing thirty lessons learnt from those cases, clustered into 7 different groups, namely, course duration and scheduling, learning platform, academic performance, student engagement, memory retention, flexibility in teaching, and course design and guideline. Implications of the findings for several groups including the educational providers, students who are about to enter colleges, parents whose children are about to start college, government, researchers, educational practitioners or educational researchers, and organizations who are sending their employees for higher training and learning have been outlined.

References

- Ball, W.H., Brewer, P., Canady, R.L., Condrey J.F., Nelson-Gill, L., Gill, T., Moran P.R., Morie, E.D., Pettit, D., Rettig, M., Strebe, J.D., Tanner, B.M. and Vawter, D.V. (1996), Teaching in the block : strategies for engaging active learners, Eye On Education, New York.

- Braun, V. and Clarke, V. (2006), ‘Using thematic analysis in psychology’, Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101.

- Bourgeois, S., Drayton, N. and Brown, A.M. (2011), ‘An innovative model of supportive clinical teaching and learning for undergraduate nursing students: The cluster model’, Nurse Education in Practice, 11(2), 114-118.

- Daniel, E.L. (2000), ‘A Review of Time-Shortened Courses across Disciplines’, College Student Journal, 34(2), 298-308.

- Davies, W.M. (2006), ‘Intensive Teaching Formats: A Review’, Issues in Educational Research. [Online], [Retrieved April 26, 2020], .

- Finger, G. and Penney, A. (2001), ‘A. Investigating modes of subject delivery in teacher education: a review of modes of delivery at the School of Education and Professional Studies Gold Coast Campus Griffith University’ paper presented at the Annual Conference of the Australian Association for Research in Education, Fremantle, Western Australia.

- Johnston, M.P. (2014), ‘Secondary Data Analysis: A Method of which the Time Has Come’, Qualitative and Quantitative Methods in Libraries (QQML), 3(3), 619 –626.

- Beattie, K. and James, R. (1997), ‘Flexible Coursework Delivery to Australian Postgraduates: How Effective Is the Teaching and Learning?’, Higher Education, 33(2), 177-194.

- Klein, R., Kelly, K., Sinnayah, P. and Winchester, M. (2019), ‘The VU way: The effect of intensive block mode teaching on repeating students’, International Journal of Innovation in Science and Mathematics Education, 27(9).

- Kofinas, A., Bentley, Y., Minett-Smith, C. and Cao G.M. (2017), ‘Block teaching as the Basis for an Innovative Redesign of the PG Suite of Programmes in University of Bedfordshire Business School’, Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Higher Education Advances, ISBN: 978-8-4904859-0-3, 21-23 June 2017, Valencia, Spain, 713-725.

- Maguire, M. and Delahunt, B. (2017), ‘Doing A Thematic Analysis: A Practical, Step-By-Step Guide For Learning And Teaching Scholars’, AISHE-J: The All Ireland Journal Of Teaching And Learning In Higher Education, 9(3).

- Merriam, S.B. and Tisdell, E.J. (2016), Qualitative research: a guide to design and implementation, Jossey-Bass, a Wiley brand, San Francisco.

- Murray, T., Barkat, I. and Pearlman, K. (2020), ‘Intensive mode screen production: an Australian case study in designing university learning and teaching to mirror ‘real-world’ creative production processes’, Media Practice & Education, 21(1), 18-31.

- O’Leary, Z. (2017), ‘The Essential Guide to Doing Your Research Project’, SAGE Publications Ltd. [Online, [Retrieved March 16, 2021], .

- Serdyukov, P. (2008), ‘Accelerated Learning: What is It?’, Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching, 1(1), 35-59.

- Smith, E. and Smith Jr, J. (2008), Using secondary data in educational and social research, McGraw-Hill Education (UK), London.

- Tatum, B.C. (2010), ‘Accelerated Education: Learning on the Fast Track’, Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching, 3(1), 35-51.

- Wlodkowski, R.J. and Ginsberg, M.B. (2010), Teaching Intensive and Accelerated Courses: Instruction That Motivates Learning, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco.

- Yao, C.W. and Collins C. (2018), ‘Perspectives from graduate students on effective teaching methods: a case study from a Vietnamese Transnational University’, Journal of Further and Higher Education, 43(7), 959-974.